The Philippines has shown the first signs of a shift away from coal financing, but industry observers said the pace is woefully slow and unlikely to pick up in the foreseeable future.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Last month, the Philippine central bank began requiring financial institutions to disclose their exposure to environmental and social risks in a policy framework on sustainable finance.

Although the sustainability circular of Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) does not explicitly ask local banks to quit coal, it encourages them to adopt “green strategies” by rewarding lending to undertakings that are environmentally sustainable while penalising those that are not.

But incoherent policies and the government’s Philippine Energy Plan, which proposes an expansion of coal in the energy mix from 22 per cent in 2016 to 41.6 per cent by 2040 to support the country’s industrialisation, are major obstacles standing in the way of coal divestment, anti-coal activist Ian Rivera said.

The Energy Regulatory Commission’s framework, for example, places renewable energy bidders at a disadvantage in the new competitive selection process to provide power most cheaply to consumers.

It requires large energy capacities that can only be provided by coal plants, “contradicting global and Philippine energy market trends of the bankability of renewables and price competitiveness”, said Rivera, the national coordinator of the Philippine Movement for Climate Justice, a coalition of more than 100 groups including indigenous people, fisher folk and farmers. It is one of the Philippines’s most active anti-coal groups.

“Policy incoherence between government regulators versus finance and monetary policies will influence the process of the shift from coal,” he said.

“

Policy incoherence between government regulators versus finance and monetary policies will influence the process of the shift from coal.

Ian Rivera, national coordinator, Philippine Movement for Climate Justice

Benjamin Castillo, managing director of the Bankers Association of the Philippines (BAP), said it is too early to tell how the banking industry will respond to the BSP circular, as it is still reeling from the impacts of Covid-19.

“We are not seeing any bank looking at the framework and immediately linking it to a coal divestment. Banks’ entire loan portfolios are at risk now during the pandemic. The timing of the framework might not make it as effective,” said Castillo, whose influential 45-member association comprises local and foreign banks.

BSP’s sustainability framework gives banks a transition period of three years to fully comply with the provisions of the circular. They have to develop their transition plan for approval six months from the issuance of the circular.

Even in the absence of a crisis, the six-month timeline is already tight, said Castillo. This is why his association has developed a transition plan template for member banks to refer to.

Who will be the first Filipino bank to divest from coal?

It is unclear if any Filipino bank is currently studying an exit from coal, but sustainability reporting—which the BSP framework requires—will help observers track their funding of energy projects. Filipino banking giants Banco de Oro Unibank (BDO) and Bank of the Philippine Islands (BPI) are the first two in the industry to publish sustainability reports.

Ayala-led BPI has the biggest share in clean energy funding with about 3 gigawatts (GW) of renewables. BDO, the Philippine’s largest commercial bank, is second, financing about 2 GW of mostly geothermal and solar projects. Together, they finance over 60 per cent of the country’s 7.2 GW of renewable energy capacity.

“

We will have to transition first to a higher proportion of non-coal to our portfolio before a total exit can happen. I cannot commit to a timeline just yet.

Chinky Lukban, head, strategic and corporate planning division, Bank of the Philippine Islands

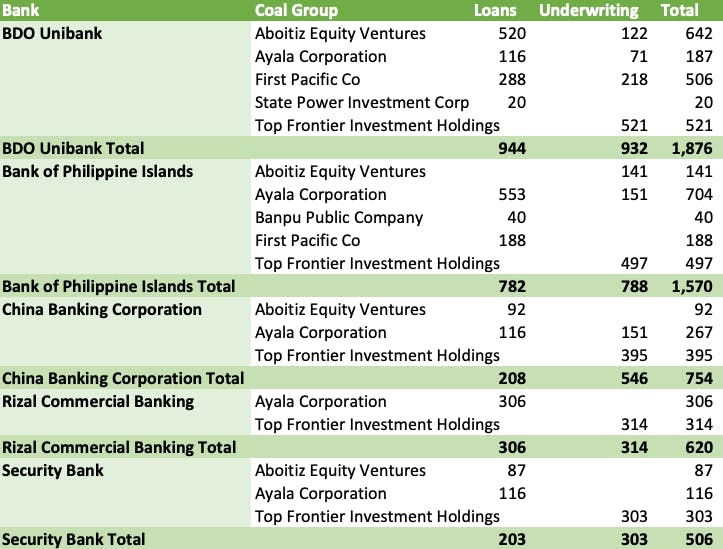

The top five coal lenders in the Philippines. BDO is the country’s largest financier of coal, lending US$944 million and underwriting US$ 932 million from 2017 to the third quarter of 2019, according to the Global Coal Exit List. The report was released by environmental non-governmental organisations Climate Strike, Urgewald and 30 partner NGOs in September last year. Source: Urgewald

BDO and BPI are also the first banks to establish a sustainable finance desk, said Marlon Apanada, convenor of Greening the Banks Initiative, a sustainable finance platform that advocated for the approval of the central bank’s circular. “They have the most knowledge and capacity but this does not automatically mean they will be the first to divest,” he said.

BPI’s head of strategic and corporate planning said the bank cannot cease coal financing yet, despite Ayala’s energy arm, AC Energy, announcing last month that it would halt new coal power projects and fully exit from coal by 2030.

“We will have to transition first to a higher proportion of non-coal to our portfolio before a total exit can happen. I cannot commit to a timeline just yet,” Chinky Lukban told Eco-Business.

As of the end of 2019, 62 per cent of BPI’s energy portfolio is made up of fossil fuels (mostly coal), while renewable energy makes up the remaining 38 per cent.

BPI was identified in a 2019 report by Global Coal Exit List (GCEL) to be one of the country’s top fossil fuel financiers, responsible for lending or underwriting US$1.57 billion to coal developers from 2017 to the third quarter of 2019.

BDO has extended US$1.876 billion to coal plant developers, including loans worth US$520 million and issuance of bonds and shares amounting to US$122 million for conglomerate Aboitiz Equity Ventures.

In Southeast Asia, no other bank outside of Singapore has dropped coal. Singapore-based financial institutions DBS Bank, OCBC and UOB made their declarations following two years of pressure from green groups and the local and international media.