The Philippines’ newly elected president Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr. has publicly expressed his intention to pursue the mammoth Panay-Guimaras-Negros (PGN) bridges infrastructure project once he takes office in late June, raising alarm among conservationists working to save the archipelago’s dwindling population of Irrawaddy dolphins.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The bridge is an integral part of the ‘Build, Build, Build’ push of the Rodrigo Duterte administration, an endeavour Marcos is intent on continuing to usher in what he calls a “golden age of infrastructure” for the Philippines.

“We are sounding a word of caution,” said marine biologist Mark De la Paz of the University of St. La Salle’s Center for Research and Engagement. “Irrawaddy dolphins are extremely vulnerable to human activity.”

De La Paz recalled how a pregnant Irrawaddy dolphin washed ashore three years ago in the coastal town of Barangay Sampinit, in Negros Occidental in the Visayas region of central Philippines. The fatal beaching was a tragic indicator of the desperate plight of the species.

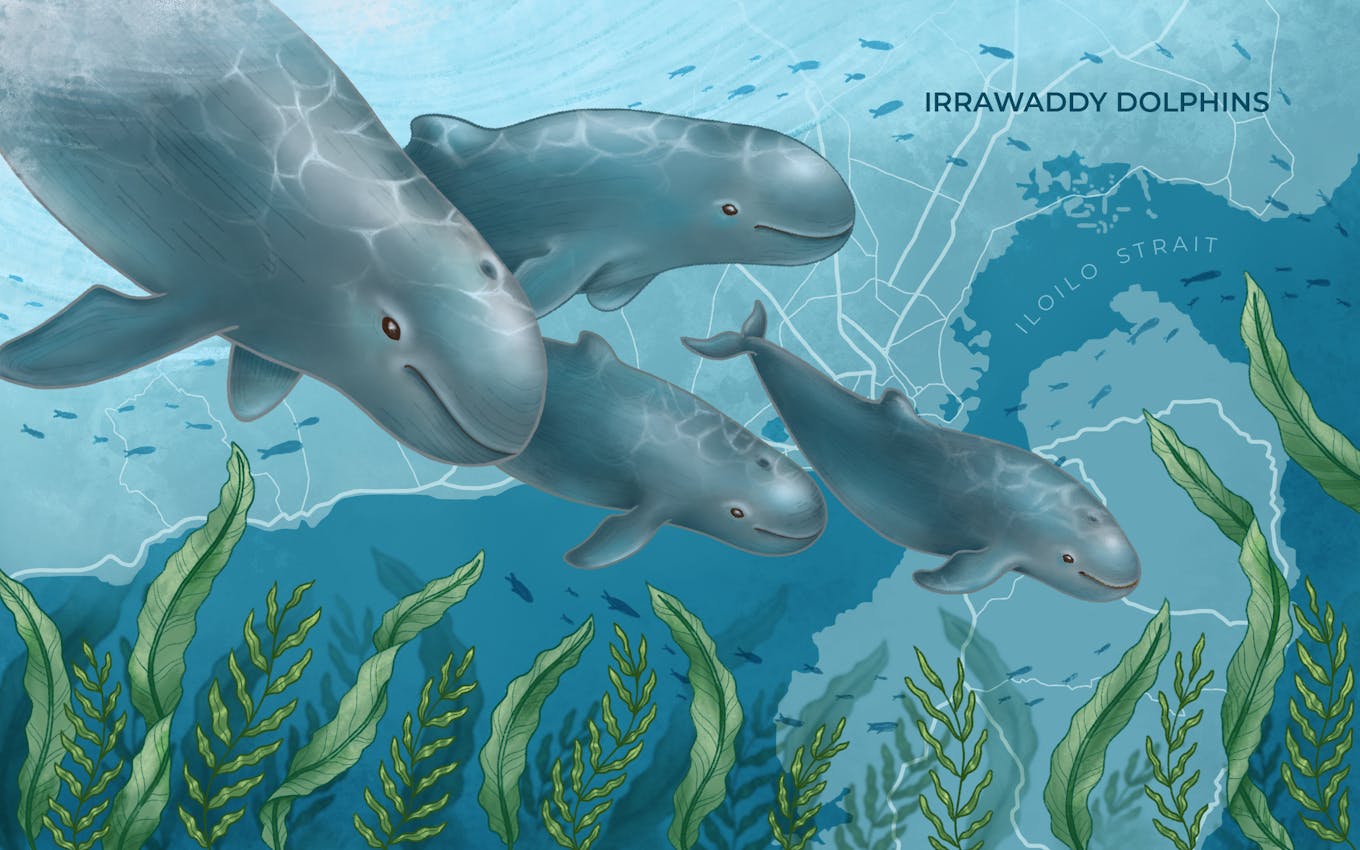

Characterised by its distinctly rounded head and its small, triangular dorsal fin, the Irrawaddy dolphin is an endangered cetacean species found in patchy subpopulations in Southeast Asia. All three of its distinct pods in the Philippines are small and threatened by prey depletion, habitat loss, boat collisions, and entanglements in fishing nets.

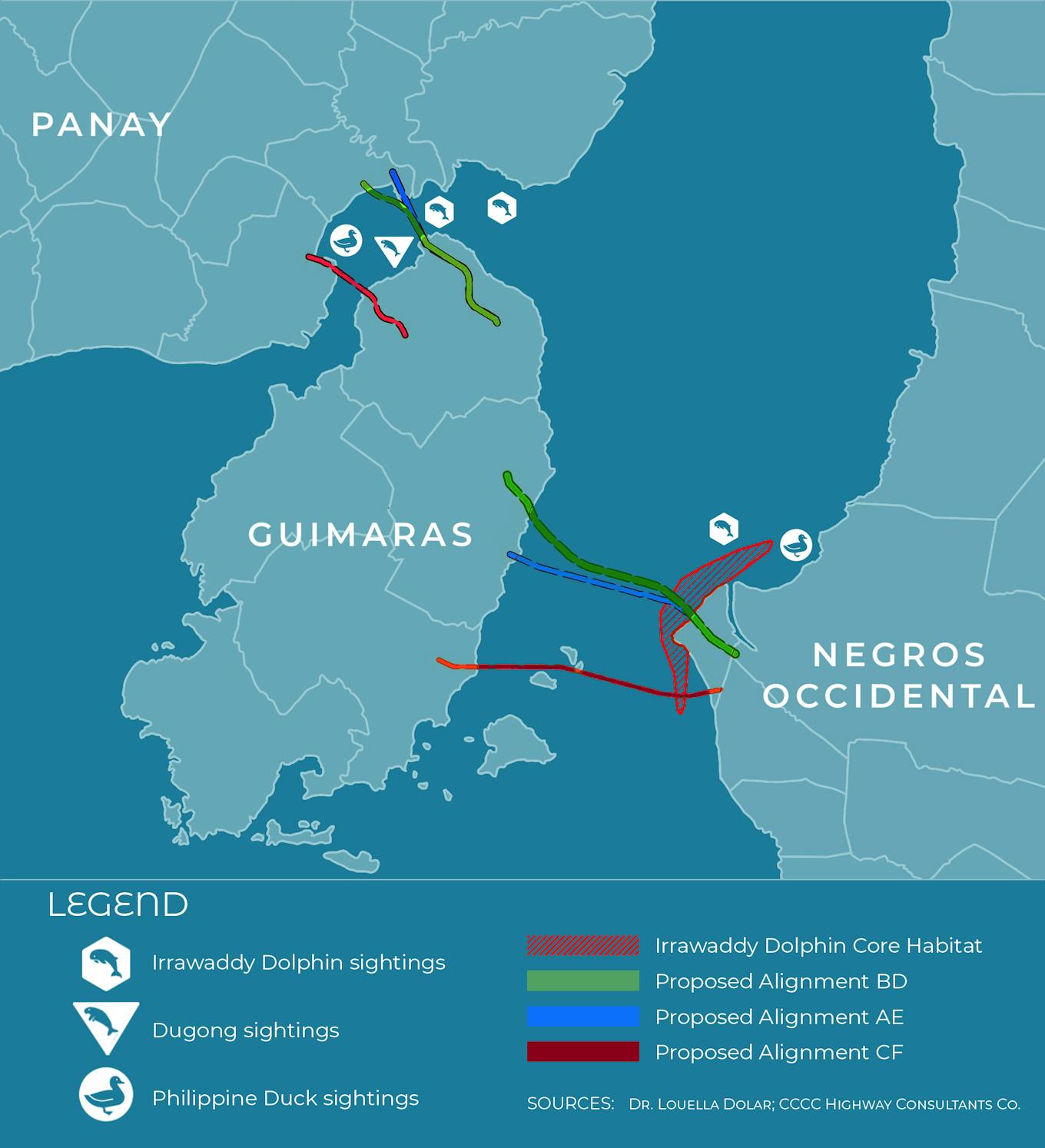

Expected to tower some 53 metres over the waters of the Iloilo-Guimaras Strait, the four-lane PGN bridges will comprise two main sections: the 13-km Panay-Guimaras Bridge and the 19.47-km Guimaras-Negros Bridge. Image: Sasha Cabais

Just 15 years since the subpopulation was first confirmed, the Iloilo-Guimaras Straits’ pod of Irrawaddy dolphins is already on the decline and on the brink of extinction. Moreso now with the planned construction of 43 kilometres of sea-crossing bridges spanning the provinces of Panay, Guimaras and Negros over the waters of the Iloilo-Guimaras Straits, bisecting the Irrawaddy dolphins’ core habitat.

Western Visayas is the fifth largest economy outside the Philippines’ National Capital Region, and the proposed bridges are expected to bring in a windfall of economic development for the region, afforded by better connectivity and ease of travel.

“

You can do conservation and also go forward economically. There doesn’t have to be an environmental trade-off.

Dr Louella Dolar, founder, Tropical Marine Research for Conservation

The bridges are vital to the ambitious ‘Build, Build, Build’ programme, a mammoth infrastructure push, promised by President Rodrigo Duterte at the start of his term in 2016, alongside other megaprojects intended to connect the entire Visayas region, the central part of the Philippine archipelago.

The most recent estimates from the University of St. La Salle Center for Research and Engagement reveal that just six to 13 mature dolphins remain in the Iloilo-Guimaras Straits. Troublingly, De la Paz said scientists have documented at least one Irrawaddy dolphin death each year for the past decade. At this rate, warned Oceana Philippines, this subpopulation could be extinct by 2040.

Characterised by a distinctly rounded head and a small, triangular dorsal fin, the Irrawaddy dolphin is an endangered cetacean species found in small patchy subpopulations extending from India’s Bay of Bengal to Southeast Asia. Image: Sasha Cabais

Dr Jon Paul Rodriguez, chair of global conservation organisation International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Species Survival Commission, said that there does not appear to be an alternative suitable habitat the dolphins could move to in the event that they are displaced by the bridges.

“The coasts of Buenavista in Guimaras Island and Pulupandan and Bago City in Negros Island] currently chosen as bridge entrances and exits are the very areas where the critically endangered Irrawaddy dolphins feed, rest, and breed,” Rodriguez told Eco-Business.

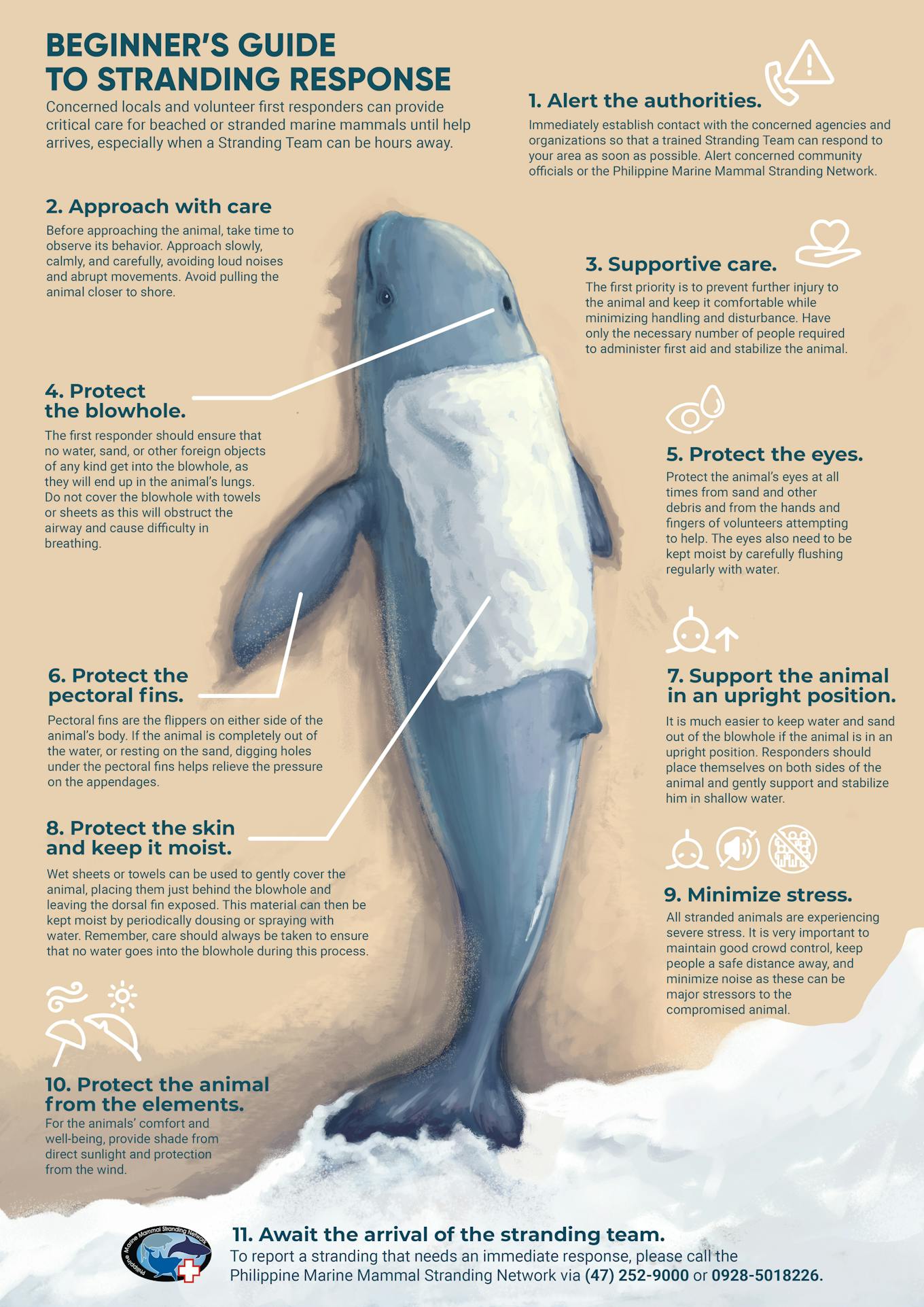

As well as concerns about habitat loss, there are fears that the noise pollution created by the construction work will harm the Irrawaddy dolphins. Sound travels five times faster in water than in air and, and as they rely heavily on echolocation, dolphins are extremely susceptible to acoustic trauma.

Loud noise can disrupt a marine mammal’s ability to communicate, orientate and forage, noted a 2021 study by Archie Veloria of the Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology of the University of the Philippines Diliman. Noise-induced stress often leads to fatal strandings.

Adult Irrawaddy dolphins can range in size between 2 and 2.8 metres long and weigh up to 130 kilograms. Image: Kaila Ledesma-Trebol

In a 2020 study in the journal Oryx, Angelico Jose Tiongson of the Institute of Environmental and Marine Sciences at Silliman University, and colleagues, pointed out that the construction of the Hong Kong-Macau-Zhuhai bridge harmed local Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins. They warned that the decline of the Irrawaddy dolphin population “is likely to be exacerbated should the Philippine government pursue plans to construct the Panay–Guimaras–Negros bridges.”

Scientists in the region have drawn attention to the notable absence of the Irrawaddy dolphins in the bridge project’s feasibility study and environmental impact statement, prepared by China-based CCCC Highway Consultants Co and KRC Environmental Services of Angeles, Pampanga. The project description for public scoping does not mention the dolphins or other vulnerable species. Meanwhile, the 588-page environmental impact statement makes only a single passing reference to the dolphins.

The threats the bridges pose to the dolphins have attracted international attention. In August 2020, the IUCN wrote to then Philippine Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) secretary Mark Villar, saying that while his organisation “recognises the importance of connecting the Panay, Negros and Guimaras Islands to facilitate efficient and safe inter-island transport,” it is concerned about the impacts of the proposed megaproject on biodiversity.

Non-profit Society for Marine Mammalogy also wrote to Villar expressing concern that construction at the proposed entrances and exits of the bridges would damage and degrade vital areas that the dolphins use for feeding and nursing their young.

“The only response was an acknowledgement of receipt from the Office of the Secretary of the National Economic and Development Authority,” Littman told Eco-Business in an email. “There was no response addressing our concerns, or indication they were being incorporated into any planning.”

Villar’s tenure as DPWH Secretary ended in October 2021. Elected a senator in the recent May 2022 Philippine elections, he remains a strong supporter of the bridges. In a statement released on March 13, he vowed to lobby for their completion.

The Iloilo-Guimaras Straits subpopulation of Irrawaddy dolphins is already on the decline and on the brink of extinction, browbeaten by habitat destruction and coastal pollution, as well as the advent of motorized boats and increased chances of entanglement. Image: Mark de la Paz

The shadow of the proposed bridges looms large over the region’s coastal and marine life, casting doubt on the long-term survival of not just Irrawaddy dolphins, but other vulnerable species and ecosystems.

Economic growth versus conservation

Expected to tower some 53 metres over the waters of the Iloilo-Guimaras Strait, the first phase of the four-lane bridge is expected to cut commutes from the city capital of Iloilo and Buenavista, Guimaras from one hour to 15 minutes.

Nueva Valencia native Kimberly Gadian is among those hopeful that the bridges will bring rapid development for her home island of Guimaras. Gadian is a graveyard-shift worker for an outsourced call centre in Iloilo City.

“Right now, I stay in a boarding house during workdays and can only go home to the island during the weekends, due to the time-consuming commute,” Gadian shares in her native Hiligaynon. The Panay-Guimaras bridge would change that, she says, but only if there are public transport routes across it to serve commuters like her, who don’t have their own cars.

A 2016 study by Nicanor Roxas Jr. and Alexis Fillone, of De La Salle University, also noted that the US$1.26-billion (P65.7 billion) Panay-Guimaras and the US$2.37-billion (P123.82 billion) Guimaras-Negros bridges have the potential to reduce emissions of air pollutants, but acknowledged that no sea vessel operators in Western Visayas have concrete emissions data.

The bridges will come at a hefty environmental price, not just threatening the survival of the dolphins.

“The bridge proposal includes the building of new roads connecting the bridge to the main highways,” said Rodriguez. “On Negros Island, this new road would destroy a portion of the Negros Occidental Coastal Wetland Conservation Area (NOCWCA).”

The Irrawaddy dolphin, alongside the dugong or sea cow, are the two most endangered marine mammals in the Philippines. Image: Kaila Ledesma-Trebol

Established in 2017, the NOCWCA is the Philippines’ seventh ‘wetland of international importance’, also known as a Ramsar site after the UN treaty under which it has been listed. It consists of 89,607 hectares of coastal wetlands encompassing the municipal waters of 10 adjacent cities and towns in Negros Occidental, including Bago City and Pulupandan.

The wetlands have been recognised for their rich biodiversity, particularly as a feeding ground for migratory birds. The site hosts five globally threatened species and two globally near-threatened species, notably the country’s largest population of endemic Philippine ducks, a species threatened by overhunting and habitat loss.

Other remarkable birds in this region include the endangered great knot, the spotted greenshank, and the far eastern curlew. Some 73 species of water birds live there, representing 41 per cent of the 177 bird species documented on Negros Island. Also inhabiting the coastal area are endangered green sea turtles and olive ridley turtles, and the critically endangered hawksbill turtle.

Rodriguez says the bridges would also bisect vital habitats for sea cows, also known as dugongs, a critically endangered species in the Philippines. Historically, the animals occurred throughout the archipelago, but their numbers have declined as they have lost 30 to 50 per cent of their seagrass habitats.

The animals have been documented grazing in the Tumalintinan Point Marine Protected Area, a sanctuary of mangroves, seagrass, and coral reefs off the coast of San Lorenzo, Guimaras. But this is one of the proposed anchor points of the Panay-Guimaras section of the bridges project. Rodriguez says dredging for the project would likely affect the seagrass beds that the protected mammals feed on.

Mangrove forests are also under threat, according to the project feasibility study. It says that, depending on the approved alignment of the bridges, the first section of the project could entail cutting down between 38,361 to 404,036 mangrove trees, mostly on Panay Island.

Call to action

With public awareness lacking, environmental group Earth Island Institute Philippines has launched a campaign to encourage local governments to implement plans scientists have laid out for saving the Irrawaddy dolphins.

“The dolphins continue to die at a rate of one individual per year,” wrote the organisation’s regional director for Asia Pacific, Trixie Concepcion, in February 2021. “This kind of mortality rate is alarming given the very small number of Irrawaddy dolphins in Negros.”

Irrawaddy dolphins are often sighted very close to the Negros Occidental coastline and seldom seen farther than 2 kilometres from the shore and are known to co-habit areas frequented by local fisherfolk. Image: Mark de la Paz

As of April 27, a campaign and petition spearheaded by the organisation had 10,526 signatures. Among other things, the petition urges central and local governments to designate the entire habitat of the Irrawaddy dolphins in the Philippines as a Marine Protected Area (MPA), and to ban or limit boats and fishing activities in particular zones.

This would mean building on existing conservation plans. In 2017, the City of Bago, through Ordinance No. 17-02, set aside 130 hectares of coastal waters as a Marine Protected Area, with 30 hectares designated as a “no take zone” where fishing and collecting of marine resources is strictly prohibited. Scientists are lobbying for a similar ordinance in coastal Pulupandan, but local legislators there haven’t been as receptive.

Conservationists say that, if the plan for the bridges goes ahead, the DPWH and other relevant government agencies must act to mitigate threats to biodiversity in consultation with local experts and marine biologists.

“If the construction of the bridge goes ahead, we would recommend that alternative sites be selected for the entrances and exits or, at the very least, no posts be constructed in the very core of the dolphin habitat,” says Rodriguez of IUCN.

He says that regional scientists need to be consulted to identify locations of least harm, and that marine mammal observers should be present during dredging and construction, to ensure that these activities are suspended when dolphins are nearby.

“Passive acoustic monitoring of the presence of dolphins should also be employed, especially if dredging and construction proceeds at night,” he says. “This may not protect this particular population, but could at least provide useful information for similar future projects in areas that are home to marine mammals.”

Vanishing heritage

Marine biologist Dr Louella Dolar, founder of Tropical Marine Research for Conservation, a research and conservation group, remains hopeful that proponents of the bridges will consider alternative exit and entrance points, to avoid impacting the core habitats of Irrawaddy dolphins off the coasts of both Pulupandan and Guimaras.

“I am aware of how important these bridges are for people’s connectivity, and the transfer of goods,” she continued. “However, you can do conservation and also go forward economically, it’s just a matter of doing it the right way. There doesn’t have to be an environmental trade-off, there is always a way of balancing the two.”

“Conservation is very difficult work because it’s utlimately about people,” she adds. “The loss of these vulnerable animals reflects on us as people. These species are the pride of the Negrense, the Guimarasnon, the Ilonggo. We shouldn’t be the generation that loses them.”

This story was produced with the support of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network under its Biodiversity Media Initiative.

Relying heavily on echolocation, marine mammals like Irrawaddy dolphins are extremely susceptible to severe acoustic trauma. Noise-induced stress often leads to fatal strandings. Image: Isaac Bravo