Cutting plastic bag use, reducing plastic packaging and redesigning products for recyclability have minimal impact in reducing the plastic waste that enters Southeast Asia’s seas.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

That was the conclusion from a study of waste management practices in Indonesia, Vietnam, Thailand, and the Philippines commissioned by Food Industry Asia, the Singapore-based trade association for the region’s food and beverage industry. FIA members include Nestlé, Unilever, Indofood and Monde Nissin, which beach audit studies have shown to be among the world’s biggest marine plastic polluters.

If consumers stopped using plastic bags, there would only be a 2 per cent drop in plastic leaking into oceans from these countries, according to the report, released in September.

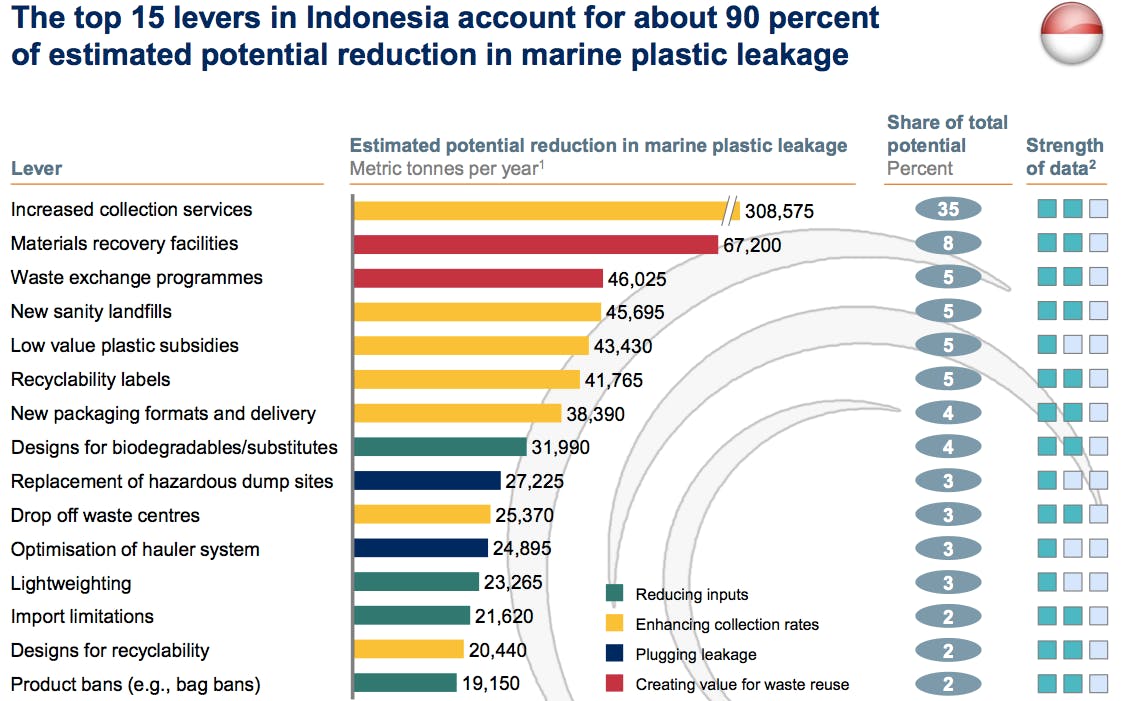

This compares to a drop in plastic leakage by 35 per cent from increasing garbage collection systems and 22 per cent from better materials recovery facilities (MRFs), solid waste plants that process recyclable materials.

The Singapore-based organisation revealed in its study that plastic bans, for instance removing free carrier bags from supermarkets, did not even rank in the top 10 ways to reduce plastic leakage in Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam and Thailand, which collectively contribute a quarter of plastic marine debris worldwide.

Possible reasons for this are ineffective enforcement and monitoring and a lack of education among consumers and businesses, the study found.

“A ban or tax on plastics might actually be counter-productive because such measures are difficult to monitor and enforce,” Edwin Seah, FIA’s head of sustainability and communications, told Eco-Business.

“These countries have already tried to ban single-use plastics but in most cities, these bans have failed as there are no viable alternatives or there’s a lack of enforcement. For instance, wet food cannot be contained in paper packaging.”

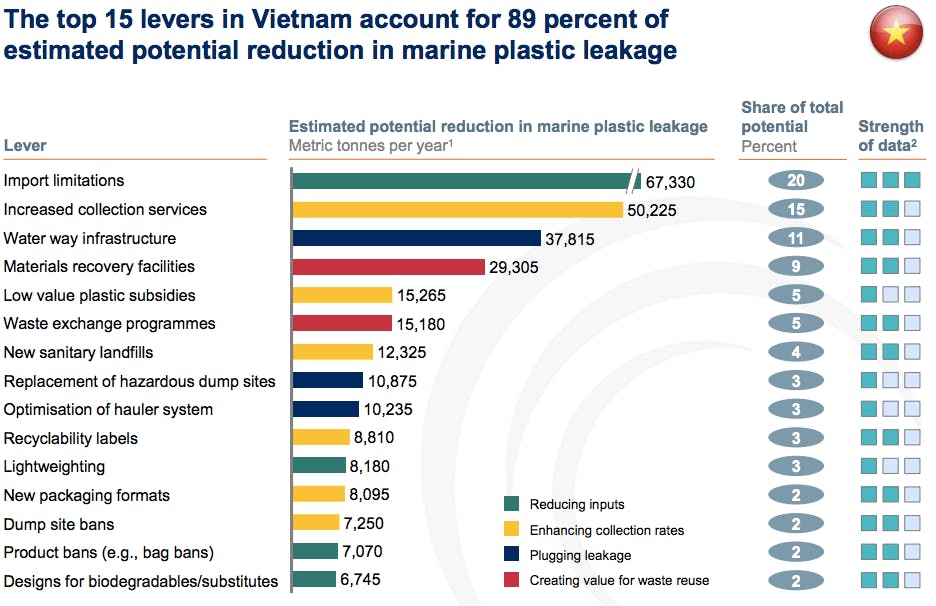

The report showed that in Indonesia and Vietnam, banning plastic bags ranked lowest in curbing plastic pollution, at just 2 per cent reduction in plastic waste for each country.

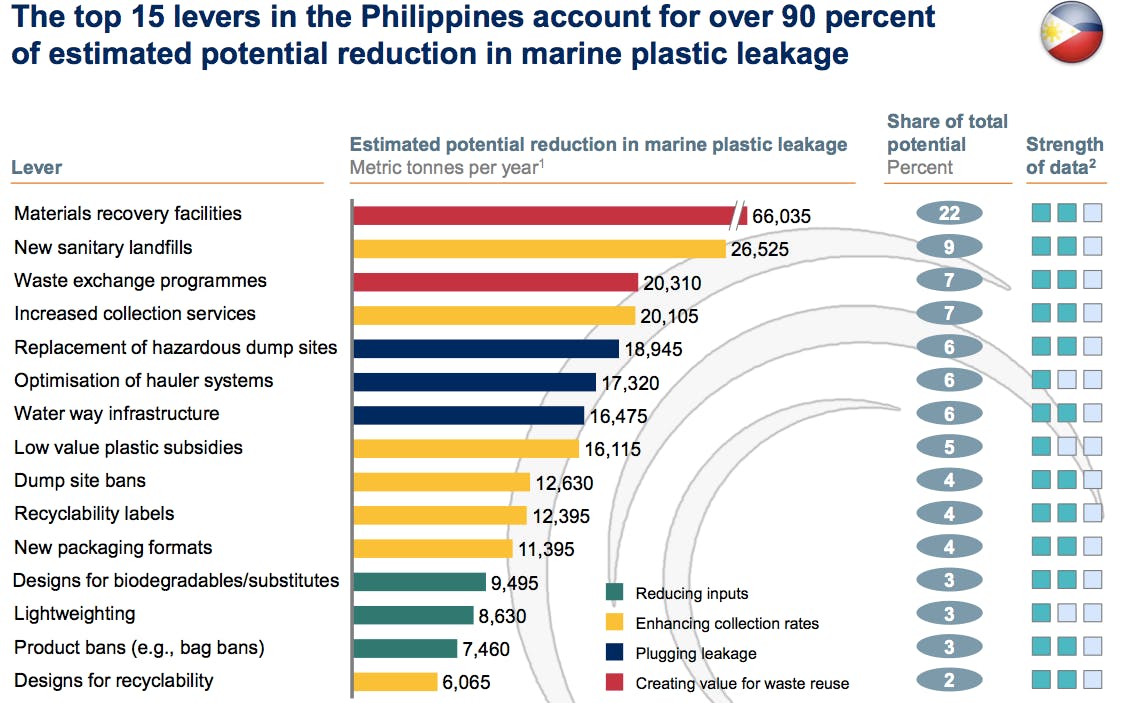

In the Philippines, designing recyclable products ranked as the least effective solution to plastic leakage, with a 2 per cent reduction, while in Thailand household garbage separation bins were the least effective.

“

These countries have already tried to ban single-use plastics but in most cities, these bans have failed as there are no viable alternatives or there is a lack of enforcement.

Edwin Seah, head of sustainability and communications, Food Industry Association (FIA)

So, what is the best way to tackle plastic pollution?

Rather than focusing on plastic consumption, Southeast Asian governments should ramp up initiatives to improve their poor garbage collection systems, the study suggested.

It showed that there would be an estimated 35 per cent reduction in plastic waste in Indonesia if its government increases its garbage collection services.

Indonesia is the world’s second-largest plastic polluter after China, producing 3.2 million tonnes of plastic waste yearly, 1.29 million tonnes of which ends up in the sea.

Source: Food Industry Asia (FIA)

Seah said that since waste collection rates are low in Indonesia, stakeholders must focus on increasing collection services rather than focusing on packaging designs and coastal clean-ups, which he said do not have significant impact.

After Indonesia, the Philippines ranks as the world’s third biggest polluter, with 1.88 million metric tonnes of plastic waste produced each year.

For the Philippines, the report recommends building more MRFs to have the most impact in solving the archipelago’s plastics problem.

The report noted a 22 per cent decrease in plastic waste if the government can meet the shortage of suitably trained staff to operate the facilities effectively.

Source: Food Industry Asia (FIA)

In Vietnam, the world’s fourth largest plastic polluter, the most effective way to curb plastic pollution would be to limit imports of waste, the study found.

When China banned plastic imports in January, Vietnam became the biggest importer of plastic waste from the United States, and the study showed that import restrictions would curb plastic leakage by 20 per cent.

Vietnam announced in July that shipping terminals would temporarily stop accepting imported waste after ships containing waste caused congestion in the country’s ports.

Source: Food Industry Asia (FIA)

As for Thailand, the report found there would also be an estimated 35 per cent reduction in plastic waste with an increase garbage collection services.

Seah said it was important for Thai stakeholders to prioritise increased collection services and subsidies for low value plastics over sustainable packaging design as most of the waste leaking into the ocean comes from uncollected waste.

Can innovation beat pollution?

The Thai authorities have tried to do their part in the Songkhla province by separating the area into many communities to decentralise collection services and promote collaboration with the informal sector.

One of the main findings of the study showed that most of waste projects are focused on large towns and cities. Seah called for more initiatives to be scaled up to cover a wider geographical area and population.

The study pointed to innovative ways to tackle plastic pollution, such as Philippine city Bayawan’s pay-as-you-throw fee, which has led to a 20 per cent drop in waste sent to landfills, and Bangkok’s introduction of global positioning systems to improve post-collection systems.

Biodegradable alternatives to plastic were also proposed, although these substitutes rate highly as effective anti-pollution measures in the study. In Indonesia, where Unilever has set up a pilot programme to recycle single-use sachets last year, green tech firm Evoware has started producing edible plastic sachets made from seaweed.