Having set a goal to reach zero carbon by 2050 and with its eye on hosting COP26 in November, the UK is now freed by Brexit from having to stick to European state aid rules and its environmental legislation, and is therefore able, should it wish, to set more ambitious standards and financially support its industries.

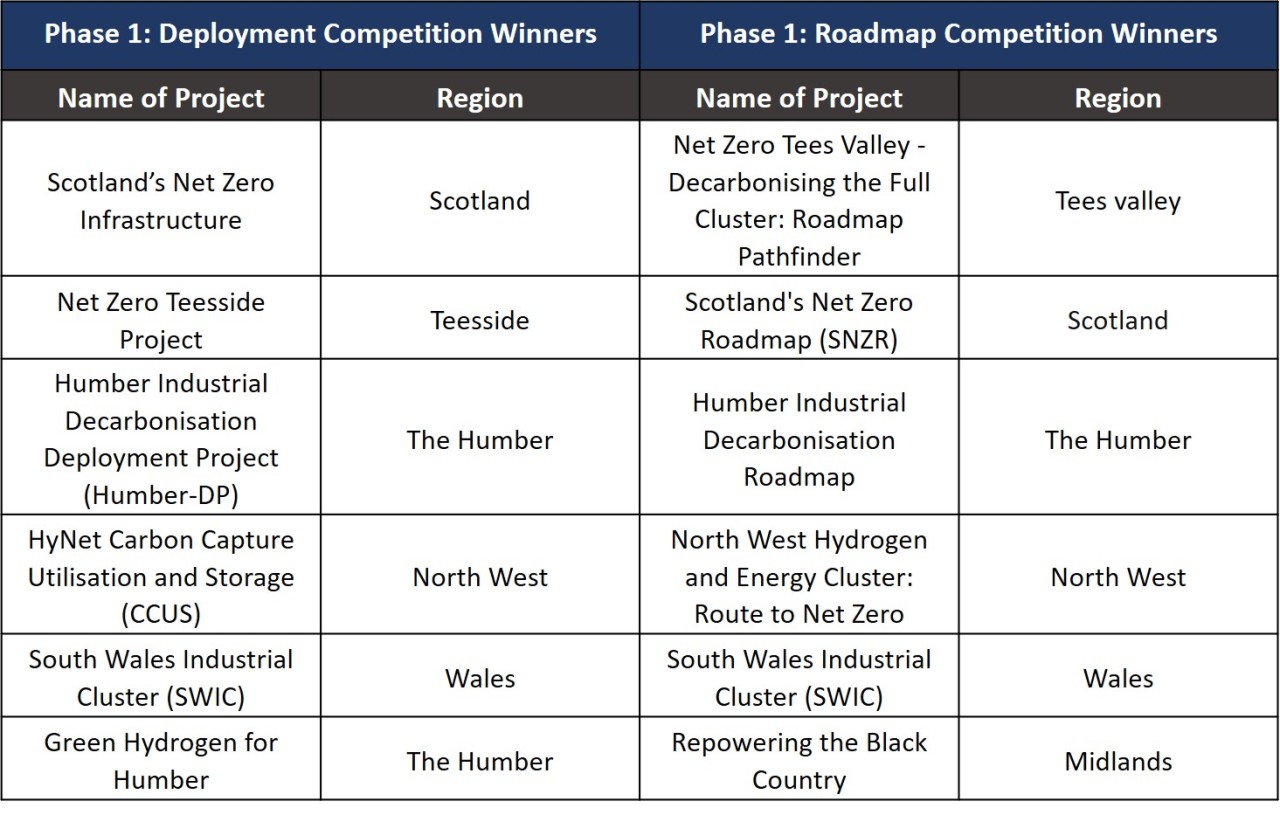

The day after it formally left the European Union, the business and industry department announced that six projects across the UK will jointly receive £8 million (USD$11 million) in funding to help them create plans for net-zero emissions industrial zones using partnerships between local authorities, academia and industry.

One scheme alone hopes this will generate over 33,000 new jobs and more than £4 billion (USD$5.48 billion) of investment. It will also become the world’s first net-zero industrial zone.

The Industrial Decarbonisation Challenge, originally launched in October 2019, will commit a total of £170 million (USD$232.77 million) towards deploying technologies like carbon capture and hydrogen networks in industrial clusters.

Pilot projects will hunt for cost-effective ways for industry to reduce carbon emissions at a large and easily replicable scale.

However, energy efficiency is not in this copy book. None of the projects show awareness of the Energy Management Standard for industry, ISO50001, which maps the easiest and most cost-effective ways to reduce emissions.

Instead, this funding is aimed at finding ways for existing inefficient and polluting industries to continue as they are, but to sequester their emissions or use them to create a pollution-free fuel (hydrogen).

This process is called carbon capture, utilisation and storage, with the utilisation part being the hydrogen creation.

But fifteen years of previous R&D around the world have not yet found a way of accomplishing either of these tasks.

Four carbon capture projects in the UK failed to pass practical or economic tests nine years ago despite much public money going into them; yet several players in those projects can be found in these six new ones.

The six projects

The six selected areas have high concentrations of industrial activity, which are expected, eventually, to collectively reduce their carbon dioxide emissions to as close to zero as possible using these methods.

Humberside’s project in the North East of England will focus on Drax Power Station in hoping to develop carbon storage and hydrogen generation.

This used to be the dirtiest coal-burning power station in Europe until it started burning large amounts of timber imported from the states turned into wood pellets – a controversial fuel challenged for its climate neutrality claims.

Because Drax already regards itself as carbon neutral, it is claiming that the end result, if successful, would be carbon negative.

This is hotly disputed by groups such as the Cut Carbon Not Forests Coalition. Other critics focus on the biodiversity loss caused by the fuel’s plantation supply chains, and the entire lifecycle emissions.

Not far away from Humberside, Net-Zero Teesside is another carbon capture, utilisation and storage project hoping to decarbonise numerous carbon-intensive businesses by as early as 2030 with up to 6 million tonnes of CO2 emissions captured each year.

A consortium of traditional fossil fuel companies has been formed led by BP and including Eni, Equinor, National Grid, Shell and Total to develop offshore carbon dioxide infrastructure in the North Sea, which is said to have over 1000Mt of storage capacity in cavities left by former gas and coal extraction.

A similar earlier carbon capture project involving Drax was one of the four that failed nine years ago (led by the Progressive Energy consortium), when it received much government and European funding under the DECC and NER300 programme.

In the northwest of England, a hydrogen production plant plans to produce “grey” hydrogen from natural gas at Stanlow Refinery at Ellesmere Port (on the Manchester Ship Canal, which transports seaborne oil for Essar and Shell), and a carbon capture and storage project in Liverpool Bay gas fields.

Over the border in Scotland, Project Acorn is already the first UK project to receive a CO2 appraisal and storage licence from the Oil and Gas Authority.

Like the other projects, it hopes to use a repurposed pipeline to take 2 million tonnes of industrial CO2 emissions each year from the Grangemouth industrial cluster to undersea storage.

It’s also expecting to pump its hydrogen into the National Gas Transmission System at a maximum proportion of 2 per cent of the total volume of gas.

The manufacturing or repurposing and burial of long carbon dioxide-carrying pipelines, with pumping infrastructure, running across the country and the safe securing of the gas in undersea repositories would in itself be a highly carbon-intensive series of engineering projects.

In the fifth project, the West Midland’s Black Country Consortium dreams of an industrial base of more than 3000 energy-intense businesses capturing 2.3 MtCO2 emissions a year. The region has many traditional metal processing operations that are carbon-intensive.

Finally, a South Wales Industrial Cluster suggests “use of hydrogen, creating sustainable aviation fuel and carbon capture usage and storage, including CO2 shipping from South Wales ports”. It’s led by CRPlus and has given rise to a zero carbon 2050 vision for the region.

What colour is your hydrogen?

Big industry is talking loudly now about the hydrogen storage age having finally arrived.

To get your head around the hydrogen production component you’d better get used to these colours – used to signify the way in which the gas is created, and its carbon footprint – as you’ll be hearing a lot more about them:

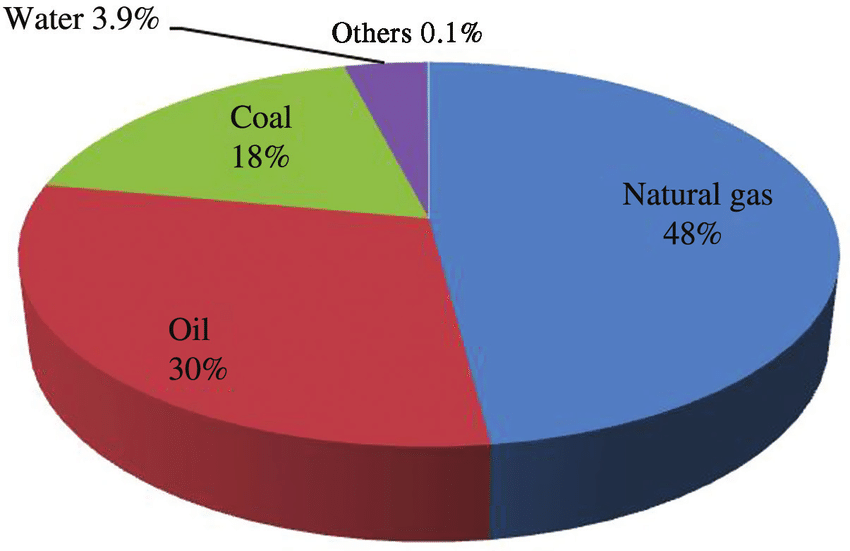

- Brown hydrogen: is created through oil and coal gasification, and produces lots of greenhouse gases (48 per cent of hydrogen is produced this way nowadays);

- Grey hydrogen: from natural gas; produces carbon dioxide (48 per cent of hydrogen is produced this way nowadays);

- Blue hydrogen: involves capturing carbon capture and storage of the greenhouse gases produced in the creation of grey or brown hydrogen; currently not proven or commercial; and

- Green hydrogen: made from renewable energy using electrolysis of water; totally eco-friendly and well-proven (4 per cent of hydrogen is produced this way nowadays).

Presently, 95 per cent of hydrogen is produced from fossil fuels. Wood MacKenzie predicts green hydrogen won’t become cost-competitive until 2040. It will only do so if there is a sufficiently high carbon tax.

Having your cake and eating it

The UK’s approach is in line with a global trend that sees oil and gas producing nations trying to protect these old-school industries, which still power the world even though they got us into this mess, by bolting on technologies that are claimed – but not proven, certainly not using lifecycle ecological footprint evaluations – to be zero carbon.

A CO2 Storage Resource Catalogue was launched last summer by the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative, the Global CCS Institute and Pale Blue Dot Energy in an attempt to position itself as the go-to global index of worldwide geologic CO2 storage resource assessments.

It contains 525 potential sites so far. Canada, Norway, the UK and the US are the main countries involved in this because their economies are dependent on oil and coal.

Russia and China are also pursuing the same goal.

Russia has already said that it has no plans to cut production of fossil fuels and will be developing hydrogen and carbon capture.

Its energy minister, Alexander Novak, has said he sees gas production only increasing and is investing hugely in gas distribution for export.

As such, pressure group Climate Action Tracker has branded Russia’s climate plans “critically insufficient”.

China projects that its pathway to its self-declared goal of carbon neutrality by 2060 will be achieved with the use of carbon capture use and storage as well as widescale electrification of transport, heating, and industry.

Energy efficiency is the cheapest way of reducing energy demand and therefore carbon emissions, and renewable energy just gets cheaper and cheaper to install.

But it seems neither of these are, alone, attractive enough to those politicians who are eager to lend their ears – and taxpayers’ money – to the lobbyists from polluting industries worried that climate change will kill off their cash cows.

This story was originally published by The Fifth Estate under a Creative Commons’ License and was republished with permission.