A report released on Monday has found that between January 2013 and July 2018, Japanese financial institutions have poured US$92 billion into coal and nuclear development—a sum bigger than the gross domestic product of Sri Lanka.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Commissioned by non-government organisation (NGO) 350.org, the research paper Energy Finance in Japan 2018: Funding Climate Change and Nuclear Risk found that Japan’s finance industry provided US$80 billion in loans and underwriting services, with half of this amount going towards coal development projects and the rest to nuclear and companies that own fossil fuel resources.

A further US$12 billion was spent on bonds and shares in companies engaged in these areas. Of the 151 financial institutions analysed, only 38 were found to be uninvolved with coal or nuclear energy projects.

Coal is a fossil fuel and energy generation from coal has been credited as the single biggest driver of climate change. Nuclear energy—produced by splitting atoms in a reactor to heat water into steam, which drives a turbine that then generates electricity—is not a fossil fuel and does not release carbon emissions. But concerns around the safety of nuclear energy have increased since 2011’s Fukushima nuclear plant disaster, prompting governments to freeze development of or shut down nuclear plants around the world.

An update of a similar paper 350.org published in 2016 that looked at which financial institutions had ties to fossil fuel and nuclear energy, one key finding of the new report is that Japan’s major insurance companies—together with its major banks—face significant exposure from shared ownership in coal financing, said Shin Furuno, Japan divestment campaigner, 350.org.

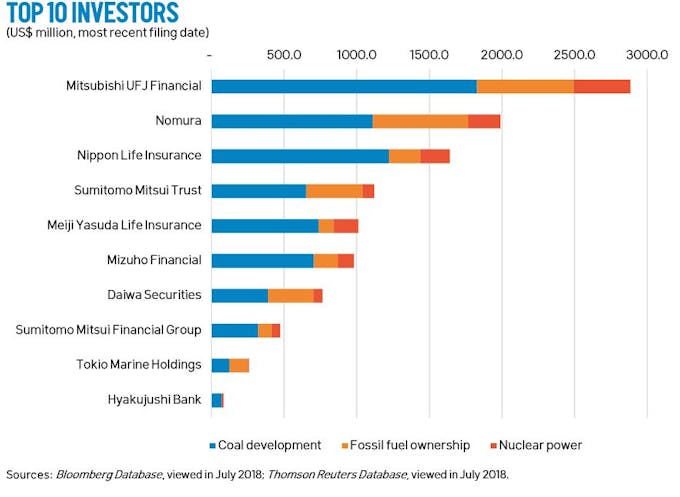

Nippon Life Insurance (NLI) was found to be the second largest investor in coal for the five-year period under study, topped only by Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (MUFG) and followed by Nomura Holdings. Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance was fifth.

But NLI, the country’s biggest insurer by revenue, in July announced that it would no longer provide loans to new coal projects or invest in coal-fired plants for environmental reasons, while Dai-Ichi Life Insurance Company in May said it would end new project financing for overseas coal plants.

Top 10 Japanese investors in coal development, fossil fuel ownership and nuclear power between 2013 and 2018. Image: Energy Finance in Japan 2018: Funding Climate Change and Nuclear Risk, 350.org

Insurers are not the only ones taking a stance. Japanese banks—Mizuho Financial Group, MUFG, Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (SMBC)—have tightened funding criteria on funds for new coal plants, but have not ruled out the option completely. Only Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank, which is a separate entity to SMBC, has committed to not financing coal power plants, regardless of location.

The Fukushima effect

But campaigners from 350.org say these policies are only the beginning. Furuno said the report would put the onus on the banks to make further disclosures about their exposure to carbon intensive assets.

Pointing out that none of the policies have amounted to a hard stop to coal financing, he added: “It’s only when we begin to see a reduction in exposure [or divestment], either through lending or investment portfolios, that we can actually say these institutions are starting to move.”

The report does not detail how much of the funding goes to domestic or international coal projects, but new analysis by Australia-based NGO Market Forces states that should the big three banks Mizuho, MUFG and SMBC—the first, second and fifth largest global lenders to new coal developments—enforce their newly minted policies, up to one-third of overseas coal plant finance would go up in smoke.

Top lenders for coal plant development. Image: BankTrack

The three banks are slated to back 10 coal-fired power projects in developing economies that have not yet reached financial closure. These projects would produce around 1.6 billion tonnes of carbon emissions, and includes the upcoming Nghi Son 2 power plant in Vietnam.

At home, coal development surged in the aftermath of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami that led to the country’s nuclear power plants, that collectively generated close to 30 per cent of the country’s electricity, being taken offline for safety reasons.

“In 2011 there was a big jump [in coal financing], then a period of stabilisation and then another big jump in 2015. What’s new here is the expansion of coal plants—35 new plants on the drawing board, but also those companies developing within Japan looking to develop overseas,” Furuno commented.

“

It’s only when we begin to see a reduction in exposure [or divestment], either through lending or investment portfolios, that we can actually say these institutions are starting to move.

Shin Furuno, Japan divestment campaigner, 350.org

So drastic was the cut in energy supply post-Fukushima that electricity prices shot up and Japan watered down its 2009 target to reduce emissions by 25 per cent by 2020 from 1990 levels, to 3 per cent. Under the Paris Agreement, the country promised to cut emissions by 18 per cent from 1990 levels by 2030—a target experts say is grossly inadequate and yet still too high for it to meet based on its current trajectory.

According to Climate Analytics, the world’s fifth largest emitter has 45 gigawatts (GW) in capacity for coal-fired generation and plans to add another 18 GW locally. It is already building 5GW.

Changing tides

Speaking about the spate of financing restrictions for coal power plants, Furuno says that pressure since the Paris Agreement is pushing these organisations to change.

“Since Paris, there’s been more focus on the responsibility of financial institutions to decarbonise their portfolios through direct finance as well as indirect finance,” Furuno told Eco-Business.

International reports have put Japanese financial institutions in the spotlight for their role in international coal development, and investors are getting antsy. He said: “Investors are saying to banks, are you managing your climate risks? Because there’s a significant stranded asset risk if these coal plants that you’re investing in are no longer operating 10 to 15 years later when renewables will be much cheaper.”

After the publication of the first report, 350.org has been encouraging investors to move their funds to banks that do not finance climate change and nuclear risk and has so far shifted US$6.5 million in a divestment campaign.

“We encourage banks to disclose that they are fossil- and nuclear-free so that people who want to be confident that the money they’re entrusting to the institution will not be used to speed up climate change,” Furuno explained. “We’re hoping smaller, more responsible banks can see it as a positive way to attract new customers.”

So far, 13 organisations have joined 350.org Japan’s divestment campaign, including Zenryouji Temple in Yokohama. Pointing to the fact that Buddhist temples and religious organisations the world over manage a lot of money through major banking institutions, Furuno said it’s an opportunity to divest and develop green finance.

“When we look at where we can manage finances from an ethical perspective, that puts pressure on institutions to meet the expectations of their customers,” he added.