Indigenous groups from Indonesia, Malaysia, and China were among the 21 global communities to receive a US$10,000 award and recognition for their conservation efforts in Paris on Monday.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

An group of four forest communities from Indonesia and Malaysia who have developed sustainable agricultural methods to support local livelihoods, a climate research project by villagers in Papua New Guinea, and an agroforestry initiative in China were some Asian efforts celebrated at the star-studded Equator Prize ceremony, organised by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

Hosted by American actor Alec Baldwin and held at the Mogador Theatre in the French capital, the prize recognises efforts by local and indigenous communities all over the world to protect nature, reduce poverty, and strengthen climate resilience.

It was first launched in 2002 by the Equator Initiative, a partnership between UNDP, governments, and non-government organisations which aims to develop and recognise community-driven sustainable development solutions. Almost 200 community organizations from 70 countries have received the prize to date.

The award organisers, in their citation, said the prize winners have secured land rights for hundreds of communities, protected millions of hectares of forests, and created tens of thousands of jobs for their communities.

One of the winners, Formadat, is a collective of four indigenous groups from the Indonesian and Malaysian regions of Borneo, who promote local heritage and livelihoods by practicing a type of wet rice farming which allows padi fields to be cultivated all year round. This rice has been recognised by international NGO Slow Food International, which creates demad for the crop in global markets.

The group also grows native fruits and actively lobbies for greater land tenure security, indigenous peoples rights and forest protection.

Lilla Raja, a Formadat member, said in a speech on behalf of several winners that “we have come to Paris to stand together to demand that world leaders reach an ambitious agreement to combat climate change, and to say that we are important partners in climate change solutions.”.

But “this agreement will not succeed without recognition of local land rights”, she added.

Helen Clark, UNDP administrator and former Prime Minister for New Zealand, who handed out the prizes, said: “These winners show what is possible when indigenous people and local communities are backed by rights to manage their lands, territories and natural resources.”

“Local and indigenous communities play an indispensable role in protecting the vital ecosystems which sustain life on our planet,” she added.

Other indigenous groups recognised at the awards included the Kayapo people from Brazil, whose activities include documenting illegal logging in their territory and developing alternative livelihoods for the community; and a coalition of Maya leaders from the Caribbean, who took the Belizean government to court to get their traditional land rights recognised.

The Munduruku People, a forest group from Brazil, were also recognised for their efforts to protect their territories in the Amazon from threats posed by hydroelectric dams, as well as illegal logging and mining.

Maria Leusa Munduruku, a member of the community, said in a statement: “We’ve come to the COP to bring international visibility and gather support for our struggle for our rights, our lands, and our rivers”.

The Brazilian government has given away indigenous land for hydroelectric dam construction without their consent, she added.

“

Too many countries are handing over indigenous land for economic development, and they get pushed aside without free, prior, and informed consent.

Gro Harlem Brundtland, chair of the World Commission on Environment and Development and former Prime Minister of Norway

Rozeninho Saw Munduruku, a member of the same community, noted that “while in Paris, we must also denounce the European companies who are responsible for supporting projects of destruction in the Amazon.”

The 21 winners, from 19 countries, were selected from a record 1,461 nominations received. The event was organised on the sidelines of the UN climate change conference in Paris, where world leaders are expected to ink a universal agreement on reducing greenhouse gas emissions to curb climate change.

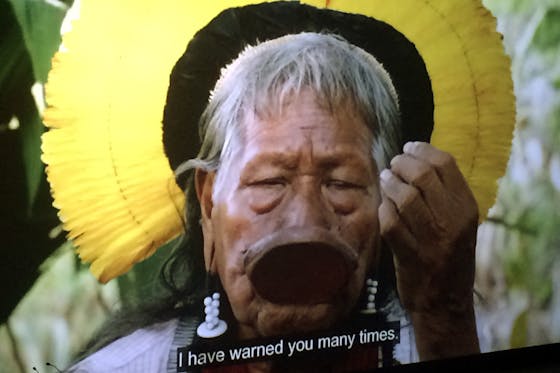

In a video screened at the awards, Chief Raoni of the Kayapo people outlines the damage done by climate change to his community. Image: Eco-Business

Research has shown that indigenous people play an essential role in achieving these climate goals, as their knowledge and resource management practices are effective in protecting carbon-rich rainforests. For instance, a recent study by the US-based Environmental Defence Fund and Woods Hole Research Center found that indigenous lands hold more than 20 per cent of the world’s tropical forest carbon.

But when indigenous peoples and local communities don’t have legal land rights, or their rights are weak, their forests become more vulnerable to deforestation, noted UNDP’s Clark.

Gro Harlem Brundtland, chair of the World Commission on Environment and Development and former Prime Minister of Norway, added in a keynote address: “Too many countries are handing over indigenous land for economic development, and they get pushed aside without free, prior, and informed consent”.

Indigenous leaders have also been murdered for resisting expansion by logging, agribusiness, and mining companies into forests. For example, José Isidro Tendetza Antún, a leader of the Shuar people in Ecuador was later found dead in an unmarked grave days before last year’s UN climate summit in Lima, Peru. He had planned to protest against a mining operation encroaching onto this people’s land.

Indigenous people’s efforts are the foundation for landscape conservation, but they also ignite social conflicts, noted Brundtland, urging governments to protect the these vulnerable communities.

“Evidence is mounting of the climate, social, and economic benefits associated with granting indigenous people control of their land,” she said.