Indonesia will require nothing less than a policy overhaul—starting with its state-owned power utility—to meet the target of having 23 per cent of its electricity generated from hydro, solar and other renewable sources in 2025, according to a new report released last week.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Unless Southeast Asia’s largest economy “radically changes” its roll-out of renewable energy, clean sources will only make up 12 per cent of the energy mix in 2025, said management consulting firm AT Kearney in its report titled Indonesia’s Energy Transition: A Case for Action. This means it would only achieve about half its target.

There are four main barriers to renewable energy growth, but at the heart of the issue is that no single agency in Indonesia is accountable for the development of renewable energy, stated the report, done in partnership with the Employers’ Association of Indonesia, or Asosiasi Pengusaha Indonesia (APINDO), which has over 14,000 corporate members across the country.

The government should make state-owned power utility PLN, or Perusahaan Listrik Negara, accountable for the deployment of renewable energy, argued the authors.

“

We believe that with a new government in place, Indonesia is now well-positioned to drive a targeted initiative to take a fresh look at how it can accelerate the adoption of renewable energy for electricity generation, especially through the lens of new policies.

Alessandro Gazzini, partner, AT Kearney

Conflict of interest

As it stands, PLN may not be fully incentivised to boost the growth of renewables, the authors said. It has a monopoly on electricity distribution in the country and is also the largest owner of fossil fuel generation assets.

“Historically, there have been many cases where PLN has not signed a power purchase agreement with renewable energy developers, even with feed-in tariff schemes,” noted the authors. A feed-in tariff is a fixed amount paid to renewable energy producers for the power they export to the grid.

Purchasing more renewable energy might require more subsidies, at least until scale is reached and lessons learnt, which would weaken PLN’s financial position, noted the report.

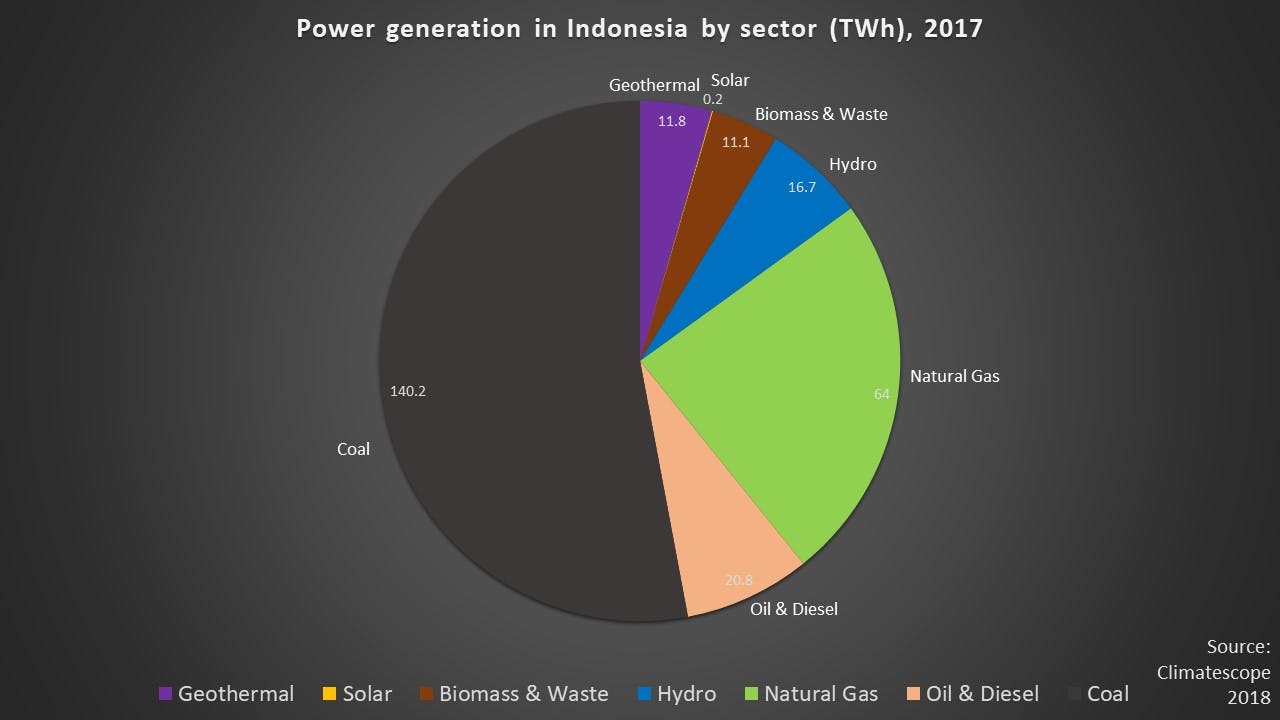

And with PLN owning and operating more than half of the coal power plants in Indonesia, rapid renewable energy growth could pose a direct risk to these assets. Coal makes up 51 per cent of Indonesia’s energy mix.

Small renewable energy projects with variable output may also expose PLN’s grids to stability issues.

The authors—AT Kearney partners Sandeep Biswas and Alessandro Gazzini, as well as its principal Sayak Datta—called for the government to provide PLN with the tools and incentives to boost renewable energy.

For instance, it should agree on and approve subsidy amounts to PLN for renewable energy growth.

Redirecting subsidies

Some unfavourable policies and regulatory uncertainty are also hindering the growth of hydro, solar, wind and geothermal power, with installed capacity a mere fraction of the total potential estimated by the government.

In 2017, the installed capacity of solar was 0.01 per cent of the estimated potential while hydro was at 7 per cent, the report noted. That same year, the country invested US$1 billion in renewables, a fraction of the US$62 billion that AT Kearney estimated is needed annually between 2018 and 2025.

Eco-Business graphic: Power generation in Indonesia by sector (TWh) in 2017. Source: Climatescope

Coal mining groups in Indonesia receive sizeable government support in the form of loan guarantees, tax exemptions and other fiscal support, said the report. In 2015, Indonesia’s post-tax energy subsidies amounted to US$97 billion, according to a recent International Monetary Fund working paper, which noted that China, the United States and Russia were among the top subsidisers of fossil fuels.

This may have been appropriate years ago when Indonesia was trying to supply electricity to many more citizens, but the government should now direct more subsidies towards renewable energy to achieve long-term economic and climate goals, said Gazzini.

Policies such as the cap on feed-in tariffs for wind and solar mean that renewables essentially compete directly with coal, rendering many clean energy projects economically unfeasible. In contrast, Southeast Asian neighbour Vietnam has stipulated feed-in tariffs for solar and wind that are higher than the tariff for power generated from conventional sources.

Renewable energy developers in Indonesia also struggle with the lack of private financing, according to the report. To tackle this, the government could expand the use of guarantees for renewable energy projects and increase the awareness of local commercial banks of renewable energy technologies.

And while Indonesia’s geography—an archipelago of 17,000 islands with an estimated 45 per cent of the population living in rural areas—poses a challenge to design and operate electricity networks, the government can provide PLN with the budget to build distribution networks in remote locations for off-grid projects. Off-grid projects are standalone power systems that operate independently of the national electricity grid.

Generating more electricity from renewables would not only enable Indonesia to reach its energy targets and combat climate change, but also enhance the country’s fiscal stability as it would make gas and coal available for export, improving Indonesia’s trade balance and strengthening the performance of the Indonesian rupiah.

‘Take a fresh look at policies’

Adoption of renewables in Indonesia has lagged strides made by other countries, said Jakarta-based Gazzini.

President Joko Widodo was re-elected this year for a second five-year term, and Gazzini said: “We believe that with a new government in place, Indonesia is now well-positioned to drive a targeted initiative to take a fresh look at how it can accelerate the adoption of renewable energy for electricity generation, especially through the lens of new policies.”

“

Indonesia should transition to renewable energy because it is the wise thing to do.

Marcel Silvius, country representative for Indonesia, Global Green Growth Institute

The Indonesian government issued a report earlier this year that showed business-as-usual practices would lead to stagnation of its economic growth in the longer term, noted Marcel Silvius of the Global Green Growth Institute, an inter-governmental organisation headquartered in Seoul. In the Low Carbon Development Initiative report, the government said that less carbon-intensive, more efficient energy systems can deliver an average of 6 per cent gross domestic product growth per year until 2045, with gains in employment, income growth and poverty reduction.

“Indonesia should transition to renewable energy because it is the wise thing to do,” said Silvius, the institute’s Indonesia representative. “Renewable energy has also many benefits for public health and offers more inclusive development options.”