In Taiwan, used coffee grounds collected from Starbucks cafes are turned into T-shirts, socks, and soaps by Taiwanese firm Singtex. Lighting giant Philips give office landlords such as in Singapore free lights in return for a share of the energy saved. In the Philippines, discarded fishing nets are sold by local communities to carpet maker Interface to make fresh carpet tiles.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

All over the world and in Asia, home-sharing platforms Airbnb, PandaBed, car-sharing services Lyft, Tripda and goods sharing apps SnapGoods and Rent Tycoon are fuelling collaborative consumption and changing the way people use goods.

These seemingly unconnected companies are all part of a new model that’s taking the business landscape by storm. Welcome to the circular economy.

While the concept cannot be traced back to a single date or originator, its underlying approaches such as cradle-to-cradle, industrial ecology and biomimicry have been practised since the 1970s and popularised by pioneers such as American designer Bill McDonough, German chemist Michael Braungart and Swiss architect and economist Walter Stahel.

It has also been linked to other concepts such as the Blue Economy, a movement initiated by Belgian entrepreneur Gunter Pauli, formerly chief executive of Ecover, which emphasises solutions based on local environments and conditions.

In recent years, the circular economy has gained traction thanks to the work of several organisations. In particular, in 2012, the charity Ellen MacArthur Foundation – set up by the retired British sailor whom it is named after – and McKinsey & Company published a first-of-its-kind report making the business case for it.

In an update of the study, Towards a Circular Economy, published last year, the authors found that the economic gain from material savings alone is estimated at over US$1 trillion a year by 2025 if companies focused on circular supply chains that increase recycling, reuse and remanufacture.

‘It’s the circular economy, stupid’

So what exactly is it? Simply put, the circular economy is one that seeks to “design out” waste and to keep products, components and materials at their highest value at all times.

Ynse de Boer, managing director at Accenture, Strategy & Sustainability for Asean, tells Eco-Business: “We’re at an inflection point where businesses understand that the circular economy is simple logic.”

Resources are finite, commodity prices are rising, and the world needs to decouple economic growth from resource consumption, he says.

The World Economic Forum estimates that 80 per cent of the US$ 3.2 trillion value of the global consumer goods sector is lost irrecoverably each year due to the current inefficient linear “make, take, waste” model.

Accenture notes in a report published last month that besides being unsustainable, this excessive use of natural resources also leads to environmental problems such as soil degradation, water pollution, waste generation and carbon emissions, just to name a few.

If nothing is done, total demand for natural resources is expected to reach 130 billion tonnes by 2030 – up from 50 billion in 2014 – and a more than 400 per cent overuse of Earth’s total capacity.

This is why in Asia, the manufacturing centre of the world, the opportunity for the circular economy is massive, says de Boer.

Accenture’s report observes that while the concept has been around for decades, what makes it “so ripe for widespread adoption now” are the disruptive digital technologies that allow massive change.

Companies, for example, can use social, mobile, machine-to-machine communication to interact with the marketplace and products in use to analyze and optimize value chains, and reduce prices for consumers, said the report.

New business models for a new world

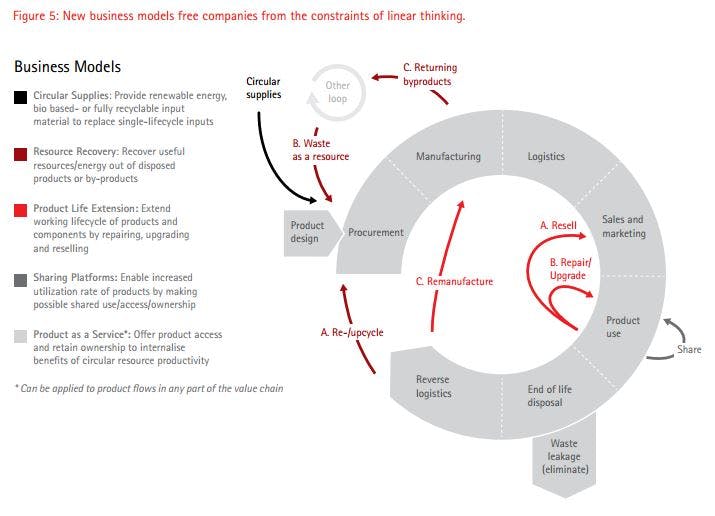

The firm identifies five business models that drive the circular economy. They are: circular supplies, resource recovery, product life extension, sharing platforms, and product as a service.

Five business models identifed in Accenture’s report, Circular Advantage - an ASEAN Perspective: Innovative Business Models and Technologies to Create Value in a World without Limits to Growth. Image: Accenture

The underlying strategy requires product vendors to think of the resources in their products as assets rather than inputs and their customers as users rather than buyers.

Some companies which have successfully applied this thinking include Singapore- based Omni United and United States casual outdoor brand Timberland, which have launched a new line of tyres in which they are collected back and recycled into soles for shoes – an example of how cross-industry collaboration can help reduce resource use.

“

We’re at an inflection point where businesses understand that the circular economy is simple logic. Resources are finite, commodity prices are rising, and the world needs to decouple economic growth from resource consumption.

Ynse de Boer, managing director, Accenture, Strategy & Sustainability for Asean

In another instance, UK firm Vodafone has started leasing phones to customers for a year, when old phones are then collected and valuable materials recycled.

In Asia, the Chinese government adopted the circular economy as early as 2002 as a way to approach its urgent problems of environmental degradation and resource scarcity.

The China Association of Circular Economy – a group of government, academic and business leaders promoting the circular economy - says that China’s circular economy grew by 15 per cent annually between 2006 to 2010 and that it will double from 1trillion yuan in 2010 to 1.8 trillion yuan in 2015.

A report by the Fung Global Institute and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, published last year, notes that China has the potential to lead the adoption of circular economies in Asia, and possibly globally.

China has the economies of scale and diversity in production processes to make remanufacturing and materials reuse economically viable, particularly for small and medium sized manufacturers, notes the report.

But even though it enacted its first Circular Economy Promotion Law in 2009, more leadership is required, especially in removing regulatory rigidities around waste in order to encourage competition and facilitate the flow of materials, says the report.

Public leadership

Junice Yeo, Southeast Asia director for sustainability consultancy Corporate Citizenship, notes that across Asia, stronger regulatory frameworks and clearer government signals are needed for businesses to respond to the circular economy.

Anne-Maree Huxley, a sustainability consultant on the Blue Economy based in Australia, says that governments should provide incentives for companies and industries to invest in circular economy technologies like some governments in Europe and the United States.

Europe, for example, has been a global leader in promoting sustainable growth. It tabled a circular economy package last year which includes an 80 per cent recycling target for packaging by 2030 and a ban on sending recyclable materials to landfills by 2025.

These are valuable examples Asian governments could consider. Governments should create policies such as shifting taxation from labour to resources, setting specific recycling targets for industries, and making companies responsible for products throughout their life cycle, says Accenture’s report.

Some such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan have done so, ensuring manufacturer responsibility by demanding that they recycle 75 per cent of their annual production. Other governments apply it to their urban planning, says de Boer. He cites Singapore’s Jurong Island, an artificial island home to the country’s energy and chemicals industry, which is set up such that one refinery’s waste stream is another refinery’s feedstock.

“This is a great example of circular economy thinking of the entire value chain,” he says.

Beyond regulation, security and privacy concerns are trickier to resolve, he notes. The sharing economy has spawned an entire ecosystem of new businesses that challenge regulations. Home sharing, for example, has been banned in European capitals Berlin and Barcelona, and may possibly be banned in Asian countries such as South Korea and Singapore, where governments are conducting public consultations.

“Things will play out differently in different countries. In some, privacy will prevail, while others will find value in such services. Hopefully, the companies and governments can find common ground,” adds de Boer.

Breaking free of business-as-usual

Besides public leadership, there needs to be a mindset shift in the private sector.

Ariel Muller, director of sustainability non-profit Forum for the Future’s Asia office, notes that one of the key barriers is “companies see themselves as part of one linear value chain”.

Enlightened companies that are breaking free of this business-as-usual thinking are finding ways to collaborate to pilot the new model and create circular waste streams, she adds.

Although market disruption in this new landscape is initially driven by start-ups, large multinationals are also creating waves of their own.

Global companies who have embraced this include H&M, which collects garments in all stores globally to close the textile loop; Philips, which offers “light as a service”- where customers pay for the performance of the lights rather than own them - to governments and businesses, car manufacturer Renault, and logistics company DHL, just to name a few.

Renault’s Eco2 cars are designed so that 95 per cent of their mass can be recovered and reused, while DHL is now championing the concept of “reverse logistics” – moving a product from its point of consumption to the point of origin to recapture its value - which it believes will be crucial in the transition to a circular economy.

They form part of a global platform by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation called the ‘Circular Economy 100’ which provides support such as consultancy and collaboration opportunities for companies to adopt circular economy strategies.

“Being accepted into this group is a confirmation of our focus on sustainability,” said DHL’s executive vice president for corporate communications and responsibility, Christof Ehrhart, in a statement.

“We all know that resources are limited, that our climate is being affected by carbon emissions, and that our consumer behaviour may lead to greater problems in the future. Joining ideas and forces to tackle these challenges is an important step for coming generations.”

Huxley says education is also key, starting with government and industry leaders and SMEs.

“Companies have to rethink their business models, adopt systems thinking, redesign their products and processes, and explore reuse, remanufacturing and recycling. Let’s not forget our students either,” she says.

So where can companies begin?

Huxley has some advice: Learn as much as you can about the circular economy and its approaches.

“If you manufacture, get a life-cycle analysis of your products to identify what you are working with, talk to your suppliers to establish how you can recycle materials as a substitute to virgin materials or up-cycle waste. Systemic thinking must guide our supply chains,” she says.

Accenture, in its report, identifies five sets of questions for business leaders to consider. Some key ones include identifying opportunities in the value chain, what is a company’s value to customers, and what technologies can be applied?

De Boer notes that today, there is a business case for all companies to go zero-waste not only because of profits but also for intangibles such as brand reputation and long-term stability.

He adds: “There’s a whole slew of business opportunities that no one has even thought about. This entrepreneurial journey is there for all businesses willing to give it a try.”

This story was first published in the Eco-Business Magazine. Read it here.