Factories that produce footwear for brands like Adidas and Nike and fast fashion online retailers including BooHoo and ASOS may be plunged under water by 2030 as the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere continues to build, and the rate of sea-level rise accelerates, according to research by Cornell university.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

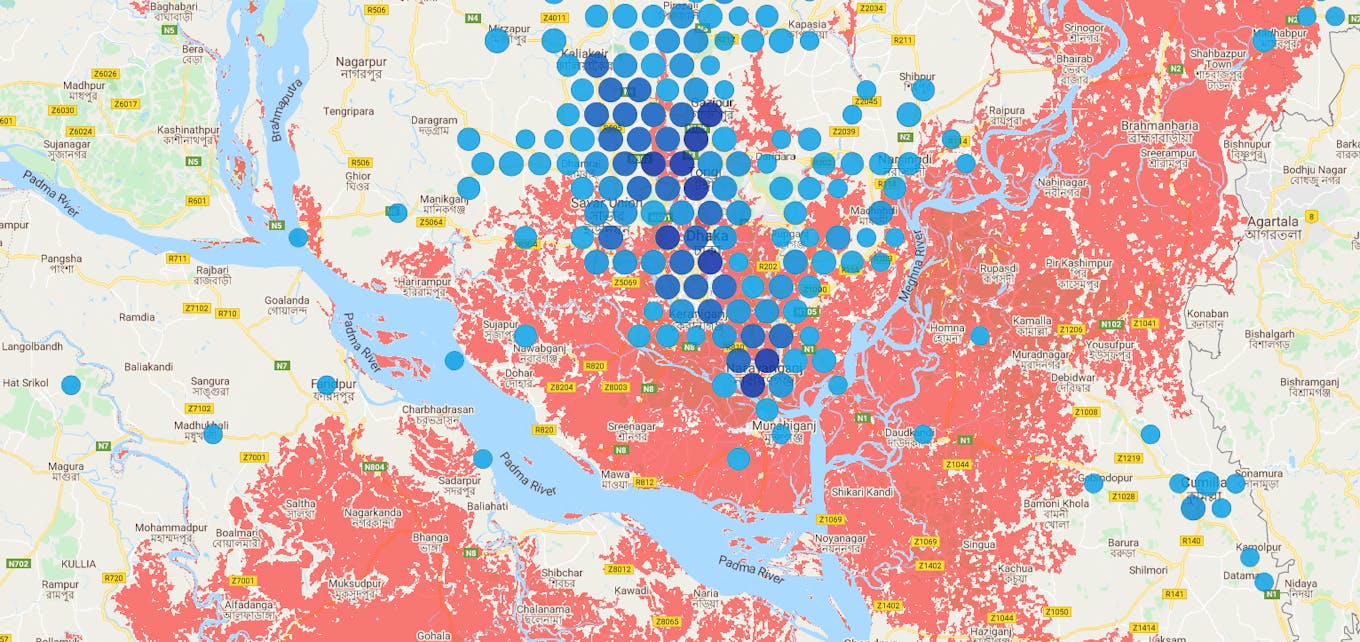

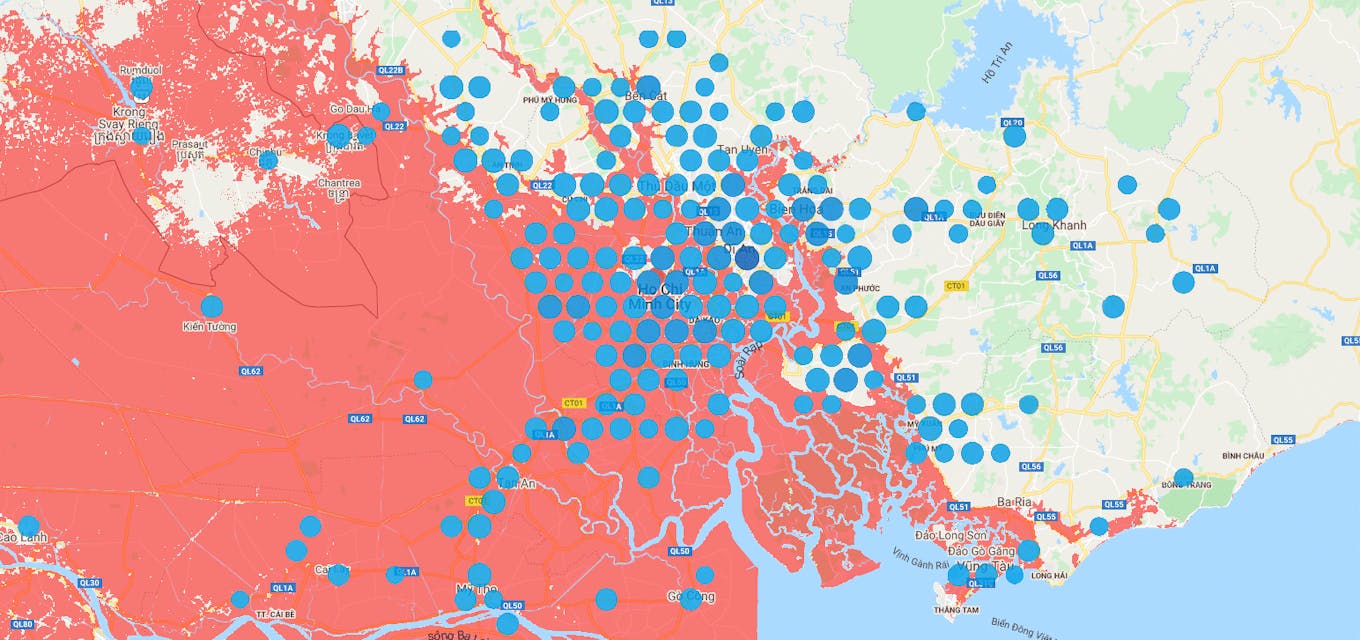

Cornell’s analysis overlaid a map of factory locations in Jakarta (Indonesia), Phnom Penh (Cambodia), Tiruppur (India), Dhaka (Bangladesh), Guangzhou (China), Colombo (Sri Lanka) and Ho Chi Minh City (Vietnam) from the database of the Open Apparel Registry, an open source mapping tool, onto data from the United States climate change think-tank, Climate Central, on where elevation will fall below the level of a coastal flood on average once per year by 2030.

In its paper, ‘Repeat, Regain or Renegotiate? The post Covid future of the apparel industry’ Cornell revealed that buyers had “no plans” to mitigate possible large-scale losses of jobs and income due to sea-level changes.

Many of Asia’s rapidly expanding cities are coastal and low-lying, making them vulnerable to rising sea levels and extreme weather such as flooding and cyclones. Around 600 million people live in low-lying coastal regions at risk of flooding, with 11 of the 15 highest risk cities in Asia, according to Verisk Maplecroft, a United Kingdom-based risk analysis firm.

“Companies operating and investing in Asian cities are going to face an increasingly stiff test to their resilience,” said analysis by Will Nichols, head of environmental research at Maplecroft.

Rising sea levels could inflict US$724 billion in economic damage to seven of Asia’s major cities this decade, a report by environmental campaigners Greenpeace cautioned in June.

Buyers, including well-known high-street brands, with very few exceptions do not own factories and risks such as catastrophic flooding belong to their suppliers.

Despite the apparent risk to factories and the people working in them, suppliers in apparel-producing areas such as Dhaka, Ho Chi Minh City and Jakarta “revealed little anxiety about the threat of flooding and dangerously high temperatures,” the report said.

Bangladesh’s industry, for now the apparel industry’s second biggest exporter, appears particularly vulnerable. Workers, except those able and willing to migrate for work, “have few options,” the report said.

Apparel and footwear manufacturing sites and 2030 projected sea-level rise in the Dhaka, Bangladesh. Projections of sea levels (red) by Climate Central overlaid with apparel and footwear factory production areas (blue) available through the Open Apparel Registry. Blue circles represent clusters of factories with darker blue circles indicating greater factory density. Image: Cornell University

High-street retailers, selling ‘fast-fashion’ that emulates catwalk fashion at a fraction of the price including BooHoo, and ASOS use factories in Dhaka that are in areas of high flood risk. They did not respond to requests for comment.

H&M Group, which buys from apparel factories in high-risk areas told Eco-Business that it, “acknowledges” the impact of flooding and other climate related disasters in its value chain.

“We are also concerned about the possible mitigation response to adapt and make our supply chain more resilient to such risk. We are working close[ly] with our business partner and collaborator like WWF [World Wide Fund for Nature] to work together to formulate such action plans as part of our sustainability strategy 2030,” the Group said in emailed comments.

Vietnam’s footwear factories located in Ho Chi Minh, which makes shoes for giants such as Adidas, Nike and Converse, are also at risk, according to the research.

Nike plans to increase its reliance on the Southeast Asian country to make its shoes, according to a report on the Vietnam government’s website on Wednesday. Production has restarted in the nearly 200 Vietnam factories that make Nike products after disruptions from Covid-19 outbreaks stopped operations at 80 per cent of supplying facilities, the government website reported.

Nike’s 2020 Impact Report acknowledges flooding as a risk to its suppliers and states that all 13 at-risk facilities the company has identified have put some mitigation measures in place. The report does not cite details about what these are and where the suppliers are located.

Using the OAR registry, together with the demarcated flood-risk area provided by Climate Central, Eco-Business found that there are about 90 facilities that supply Nike that will be impacted by flood by 2030.

Nike and Converse did not respond to requests for comment. Adidas declined to comment on the issue.

Ho Chi Minh City’s projected 2030 sea levels will consume nearly 55% of the mapped apparel factories. Projections of sea levels (red) by Climate Central overlaid with apparel and footwear factory production areas (blue) available through the Open Apparel Registry. Blue circles represent clusters of factories with darker blue circles indicating greater factory density. Image: Cornell University

“The analysis from Cornell…demonstrates the urgency of the issues facing our sector and is a sobering reminder that we can no longer afford to wait to take action towards a more sustainable future,” Natalie Grillon, executive director of the OAR said.

However, action is unlikely to come from the consumer, according to Jason Judd, report author and executive director at Cornell University. “While the gap between the way consumers talk about worker and environmental protections and the way they buy may be narrowing, the data shows it cannot be the basis for big, urgent change,” Judd told Eco-Business.

Instead, brands need to focus reporting requirements to track outcomes and impacts. “Public regulation, trade policy and bargained agreements to raise the floor for the entire apparel industry,” Judd said.

A growing number of countries are pushing companies and financial institutions to report their climate-related risk on a mandatory rather than a voluntary basis in-line with guidelines set by the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

The task force encouraged “all organisations to implement these recommendations” in its revised guidelines, published in October, in anticipation of climate-related issues being determined as material to a firm’s balance sheet.

Time is ticking for the world’s biggest fashion brands, according to Nichols. “With investors and regulators increasingly concerned about broader ESG issues, organisations unable to account for the full spectrum of environmental threats and impacts will face some difficult conversations.”