In a week’s time, Singapore shoppers without their own shopping bags will need to top up supermarket purchases with spare change, as a five-cent (US$0.04) plastic bag charge goes live across the country.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Or some of them could try to slip through the “honour”-based system that many retailers have chosen to implement at the ubiquitous self-checkout counters, environmentalists fear, denting the effectiveness of a major initiative to cut down on single-use plastics in the city-state. Plastic bags are one of the major contributors to Singapore’s domestic plastic waste stream.

The bag charge applies to about 400 large supermarkets, out of 600 supermarkets islandwide. While cashiers will be doling out the charges at manned counters, several operators are leaving it up to customers to pay for plastic carriers that are available to them at self-checkout counters.

Such honesty schemes are being used by major operators such as NTUC FairPrice, which has over 100 stores islandwide, DFI Retail Group, which has 75 supermarkets under the Cold Storage and Giant brands, and Prime Supermarket, with 24 outlets.

Meanwhile, Sheng Siong is introducing self-checkout kiosks with plastic bag dispensers that add the fees straight to customers’ receipts, instead of relying on shoppers to key in the number of bags they use.

The retailer is targeting introducing 30 such counters at six shops by next week, and 50 counters by year end. Unlike its competitors, few of Sheng Siong’s 68 supermarkets have existing self-checkout options. A spokesperson declined to reveal the setup costs of the bag dispensers.

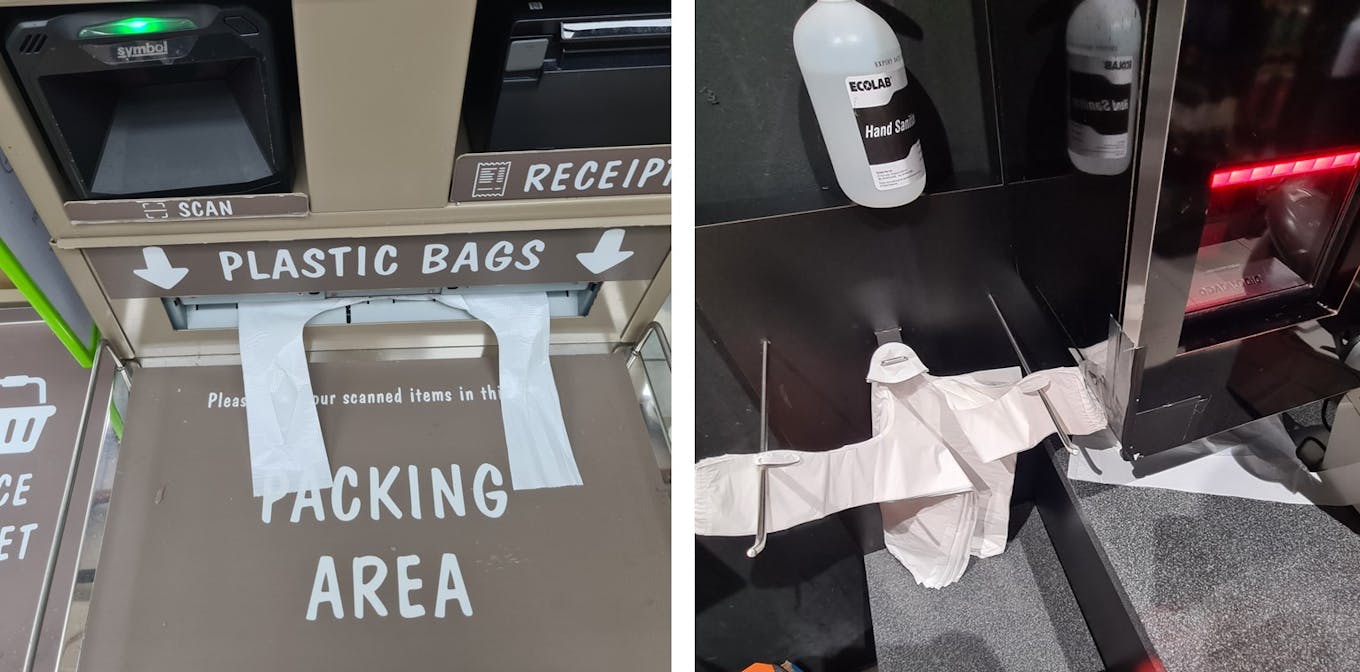

Checkout booths at different supermarkets in Singapore. Sheng Siong is rolling out kiosks with built-in dispensers that track the number of plastic bags that shoppers use (left), while other major supermarkets are opting to continue with existing hardware that stores plastic bags externally, such as this booth at a Cold Storage outlet (right). Images: Eco-Business/Liang Lei

Environmental policy observer Audrey Tan, in response to news of FairPrice’s plan, said it is an “unfortunate case of one step forward and 10 steps back”, and feels like greenwashing.

Tan wrote on her LinkedIn social media page that past trials with bag charges should have made clear if customers can be trusted to pay up.

FairPrice had trialled bag charges at a few stores in 2019. A survey by the supermarket then found that just over 70 per cent of shoppers supported the initiative, with the rest believing free shopping bags are an expected free service, and that they are needed to line trash bins at home.

There are other bags available, such as bread packaging, to store wet waste, Tan told Eco-Business, adding she wonders why more supermarkets do not adopt plastic bag dispensers for self-checkout booths.

Environmental advocate Robin Rheaume, who runs a Singapore recycling information website, said there may be a “relatively high” number of people – she expects about 30 per cent – not paying for bags at self-checkout counters.

They could either skip the charge as a personal protest, or genuinely forget to pay in a rush, especially with “a queue of people breathing down their neck”, Rheaume said.

The bag charge would unlikely make a meaningful impact on climate change – Singapore incinerates its waste which generates carbon emissions – Rheaume said, but added it may have a knock-on impact on people’s sustainability behaviour.

“So how the system is implemented, and not simply having a bag charge, is worth thinking about,” she added.

Shoppers took about 820 million plastic bags from supermarkets a year, according to a 2018 study by the Singapore Environment Council. They make up part of the 200 thousand tonnes of disposables that residents tossed in 2020, against nearly 6 million tonnes of total waste produced that year, according to the National Environment Agency.

Rheaume suggested putting barcodes on plastic bags, which she had seen implemented in Iceland. A spokesperson for Prime Supermarket in Singapore said its plastic bags will come with barcodes for the five-cent charge.

Are honour-based systems legal?

Legislation for Singapore’s plastic bag charge, passed March this year, states that retailers “must” collect at least five cents for each disposable carrier bag.

Retailers could be fined up to S$10,000 (US$7,400) and jailed up to three months for flouting the rule. But if hauled to court, they are allowed to argue their innocence by showing that “reasonable care” was taken to enforce the bag charge. It has led to questions online on the legality of the supermarkets’ honour systems in implementing the plastic bag charge.

Tiong Teck Wee, a partner at law firm WongPartnership, said it is not possible to say whether supermarkets have complied with the laws governing the plastic bag charge, just based on them adopting an honour system.

Tiong noted that there are already staff assisting shoppers at self-checkout counters today.

“It is hard to say at the moment where on the spectrum supermarkets are going to land [on enforcing the plastic bag charge], but they do not appear to be on either extreme [of being too stringent or lax],” he said.

But Meryl Koh, director of intellectual property and dispute resolution at law firm Drew & Napier, said retailers could indeed be breaching the law if they cannot charge for every plastic bag used.

Retailers opting for honour systems could find it hard to prove they have taken reasonable care, since some shoppers can slip through the system, though it is still unclear what “reasonable care” actually means in practice, Koh said.

Retailers could get staff to do additional checks on customers’ plastic bag payments, or hand out bags to shoppers only after payment, Koh suggested.

A Singapore lawyer, speaking anonymously due to existing work with retail clients, said a sizable mismatch between the number of bags dispensed and charge collected could denote a lack of reasonable care.

Retailers need to report such figures annually to the government. They could be asked to implement stronger measures if a large mismatch is reported, the lawyer said.

A FairPrice Group spokesperson said frontline staff have been trained to be “vigilant” in getting customers to adhere to the charge, and that checkout areas are already manned by security cameras.

The spokesperson said FairPrice will monitor its honour-based system and assess if modifications are needed. FairPrice had earlier said no extra staff will be rostered at the self-checkout counters to monitor that shoppers pay their plastic bag fees, according to local newspaper The Straits Times.

A DFI Retail Group spokesperson said all team members are briefed and trained on necessary procedures around the bag charge. A Prime Supermarket spokesperson said staff are on-hand to assist customers at self-checkout counters.

Singapore’s National Environmental Agency (NEA) said it will do compliance checks, and that the information retailers publish on bags dispensed and fees collected needs to be audited. The agency will direct operators with incomplete or inaccurate information to rectify or recompute their numbers, its spokesperson noted.

Dozens of jurisdictions globally charge for plastic bags, and some have likewise grappled with getting customers to pay up.

Hong Kong doubled its plastic bag charge to HK$1 (US$0.12) at the end of last year. The government told retailers to put plastic bags further from self-checkout counters, and conducted plainclothes spot checks, according to newspaper South China Morning Post.

Officials in Denver, Colorado in the United States have also admitted some shoppers jump the bag charge at self-checkout counters, where they self-declare how many bags they are taking.

Single-use plastics are major culprits in global marine pollution. They are also produced from fossil fuels, the dominant cause of man-made global warming.

In Singapore, the concern is that incinerating such waste adds to its carbon emissions, and takes up space in its only landfill, which the authorities are trying to extend the lifespan of past 2035. Only 6 per cent of Singapore’s plastics were recycled last year and the city-state’s domestic recycling rate dropped from 13 per cent to 12 per cent last year.

Free plastic bags have been slowly disappearing in Singapore. Many convenience store chains already have plastic bag charges in place. Furniture retailer Ikea pulled free bags from its megastores in the city-state a decade ago.

Note: Paragraphs 22 to 24 have been added to reflect additional views.