In recent years, South Korea’s rampant state funding of overseas coal power plants earned it a reputation as one of the world’s worst climate villains. But the colossal sums pumped into the dirty fuel over the past decade have been eclipsed by finance funnelled to oil and gas, according to a new analysis that is set to further tarnish the country’s image on the international stage.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

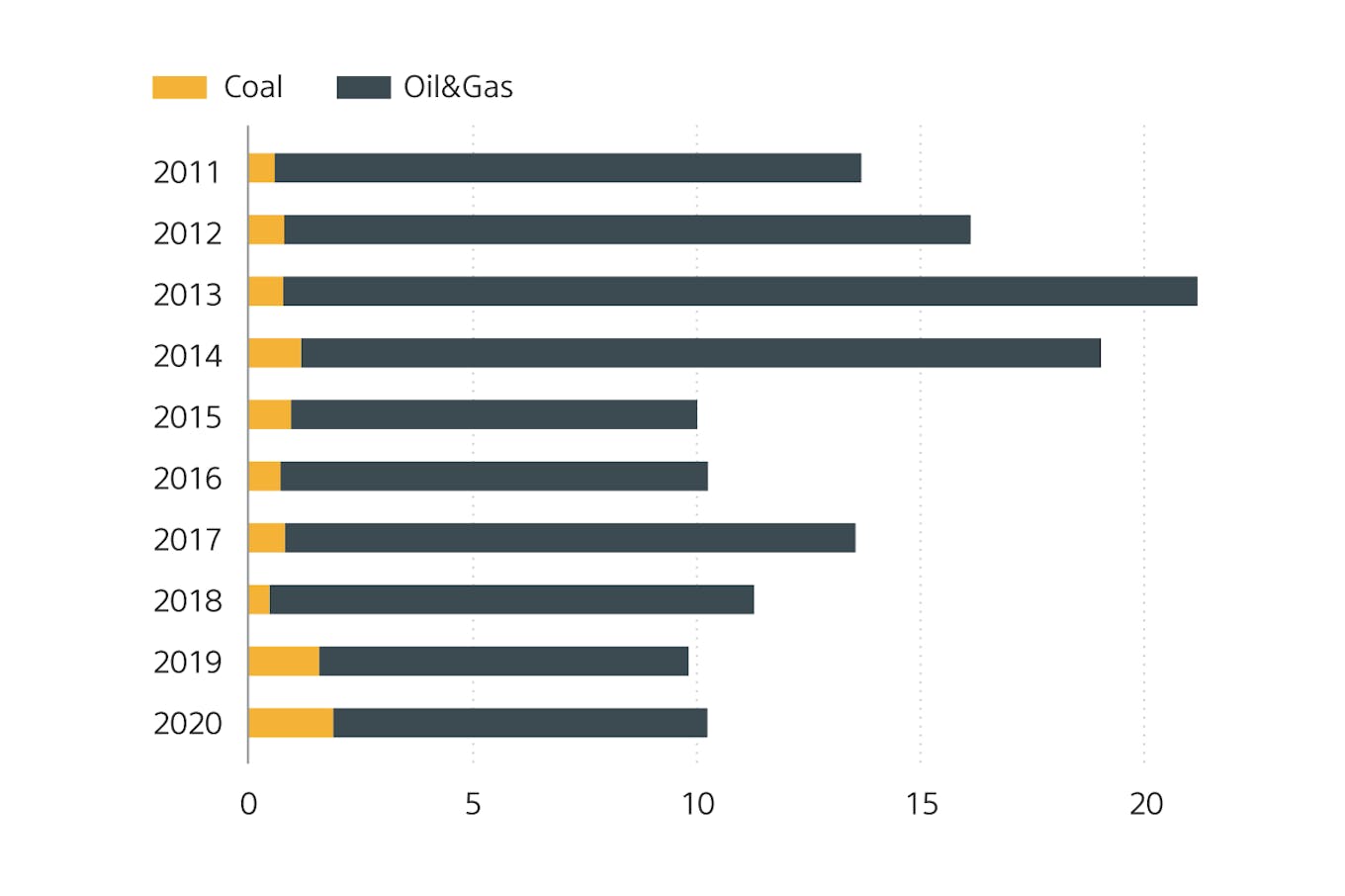

The report, by Seoul-based research and advocacy organisation Solutions for Our Climate (SFOC), reveals that Korean public financial institutions such as the Export-Import Bank of Korea (KEXIM), Korea Trade Insurance Corporation (K-SURE), and Korea Development Bank (KDB) channelled a staggering $127 billion into overseas oil and gas projects from 2011 to 2020.

That’s nearly 13 times larger than the nation’s controversial support for the coal industry over the same period, which amounted to about $10 billion, shows the study, titled Fueling the Climate Crisis: South Korea’s Public Financing for Oil and Gas.

“The figures are shocking,” said Sejong Youn, climate finance programme director at SFOC and lead author of the report. “South Korea has long been criticised as a climate villain for providing massive support to overseas coal power projects, but the country’s newly revealed public finance to overseas oil and gas completely dwarfs its backing of coal.”

Breakdown of South Korean public financing for fossil fuels by year. Image: SFOC

While the analysis does not provide data on emissions resulting from Korea’s public financing, the overwhelming difference in the scale of financing means that the contribution of oil and gas funding to global greenhouse gas emissions is likely to be larger than that of coal investments, Jeeyeon Song, SFOC’s communications officer, told Eco-Business.

The oil and gas industry is responsible for nearly half of global carbon dioxide emissions and has recently come under scrutiny for its emissions of methane, a greenhouse gas that boasts a 100-year global warming potential about 30 times that of carbon dioxide. It is the second-biggest driver of human-caused climate change today.

The Paris-based International Energy Agency (IEA), widely considered the leading voice on energy transition issues, estimates that the sector emitted 82 million tonnes of methane in 2019—about three times the carbon dioxide equivalent that Germany released into the atmosphere that year. Despite various industry-led initiatives, methane emissions have remained high.

In a recent landmark report, which examined what it will take to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 and stay within safe limits of global heating, the IEA warned that investment in new oil and gas exploitation and coal-fired power stations must stop immediately, and the demand for oil and gas would need to drop by 75 per cent and 55 per cent, respectively.

Enormous sums

SFOC’s study shows that loans and guarantees have been dished out both to state-owned enterprises and private sector companies in all segments along the value chain, with $32.2 billion (25 per cent) invested in upstream projects such as exploration and drilling, $49.7 billion (39 per cent) in midstream projects including pipelines and storage, and $45.1 billion (36 per cent) in oil refining, gas processing and other downstream sectors.

Geographically, the Middle East hosts most ventures backed by Korean banks ($35.3 billion), followed by Central Asia, which includes Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Russia ($10.1 billion). The biggest recipient was Kuwait, with $7.6 billion deployed. Oil and gas projects across Southeast Asia, South Asia, and East Asia received $6.8 billion.

In the upstream sector, Australia is home to most Korean-backed ventures, with $3.6 billion invested, followed by Mozambique with $2.7 billion, and the United States with $2 billion. Among projects funded is the $5.6 billion Barossa-Caldita gas field off the northern coast of Australia, which has come under fire for its potential to emit twice as much carbon dioxide as other gas fields due to high content of the heat-trapping gas present in the reservoir.

The most notable beneficiaries in the industrial sector are major Korean shipbuilders, including Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering, Samsung Heavy Industries, and Hyundai Heavy Industries. Nearly half of the country’s oil and gas public finance was invested in shipbuilding and offshore plant financing, with liquefied natural gas carriers receiving the most at $23.1 billion. South Korea’s shipbuilding industry is the world’s second-largest after China’s and an integral part of the country’s economy.

Rising pressure

SFOC’s analysis warns that South Korea’s financial backing for oil and gas increases transition risk for domestic industries and stranded asset risks for state banks while bucking global public financing trends.

Last December, the United Kingdom announced it would end taxpayer support for fossil fuel projects overseas “as soon as possible”—albeit with “limited exceptions”—to support a transition to low-carbon energy. The following month, the European Investment Bank, the world’s largest multilateral lender, pledged to stop all funding for fossil fuels before the end of the year.

Recently, the United States narrowed its fossil fuel financing through multilateral development banks, though it left the door open for fossil fuel-based energy financing in developing countries if clean alternatives are “unfeasible”. And two Swedish export credit agencies, Exportkreditnämnden (EKN) and Svensk Exportkredit (SEK), are set to cease all financing for fossil fuel exploration and development by 2022.

Financial markets, too, have begun to respond to the industry’s shifting economic tides. A 2020 report by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), a global energy finance think tank, argued that progressively tighter oil and gas lending guidelines and market trends indicated that investors had begun to reassess financial strategies amid looming stranded asset risks.

Like other nations, South Korea has come under pressure to reduce climate impacts and redirect financial flows to low-carbon development as this year’s United Nations climate conference (COP26) approaches and scientists sound the alarm bells over irreversible climate disaster if emissions keep soaring. After China and Japan, South Korea is the world’s third-largest financier of coal, the biggest culprit behind man-made climate change. It is also the seventh-biggest emitter of carbon dioxide globally.

Following last year’s declaration that South Korea would go carbon neutral by 2050, President Moon Jae-in pledged at a climate summit hosted by United States President Joe Biden in April that the East Asian nation would stop state funding for coal power beyond its border and commit to a tougher 2030 emissions reduction target by 2022, although the government reportedly mulled backpedalling from the announcement a month later.

Dongjae Oh, a researcher at SFOC and co-author of the report, said: “Further investments in oil and gas projects go against the public’s interest by contributing to climate disasters and is a direct contradiction to the country’s carbon neutrality drive.”

“To minimise risk to the Korean economy and public funds, and to build demonstrate climate leadership, Korea needs to rapidly stop the pipeline of overseas fossil fuel projects like public institutions in the United Kingdom, Sweden, and United States.”