By Hannah Fernandez and Liang Lei

28 November 2023

Meet the people pushing to protect one of the most vulnerable parts of the world to global warming at the COP28 climate talks in Dubai.

Southeast Asia, home to 680 million people, has a complex relationship with climate change.

None of the region's nations industrialised early enough to warrant historical responsibility for climate breakdown. But Southeast Asia is nonetheless a growing carbon emitter, and one of the only regions in the world where coal is growing in the energy mix.

While the archipelago is at the forefront of climate risks, individual nations differ dramatically in their ability to respond to intensifying storms, floods and droughts – Singapore, for instance, has a per-person gross domestic product nearly 80 times that of Myanmar.

At COP28, nations will spar on disaster funds, the workings of carbon markets, and the role of fossil fuels – issues Southeast Asia have huge stakes in.

Eco-Business is featuring five Southeast Asians who will be attending COP28. Here's more about their work, concerns and aspirations for the negotiations in Dubai.

Robert Borje

A climate negotiator from the Philippines

Robert Borje grew up in Mindanao, the southernmost island group in the Philippines.

In a speech at a climate justice roundtable on Thursday, he shared how the 1990s was a tumultuous time of armed conflict and poverty in the Muslim region. He was not particularly conscious of climate change back then.

It was only in 2013, when he was a diplomat for the Philippines at the United Nations, that Typhoon Haiyan – the deadliest storm to smash into the archipelago – moved him to the urgency of curbing global warming.

Today, Borje is commissioner of the government body that represents the Philippines in the negotiations at COP.

It will be his second time attending COP as vice chairperson of the Philippine Climate Change Commission since he was appointed to his role in March last year. His term will run until 2027.

The Philippines is eyeing loss and damage as a key issue that it will be lobbying for, as questions over how the fund will operate, who will pay for it, who will benefit, and how it will be governed are expected to be tackled at the conference. Borje will be participating in the debate for climate finance, along with delegates from the departments of finance, energy, science and technology.

The career diplomat said the US$9.9 million worth of local climate funds approved by the commission in October is not enough. Since 2012, the government has been mandated to direct at least US$18 million into what is called the People’s Survival Fund used for climate change adaptation initiatives.

“What we want is a replenishment of the fund and … a drastic improvement in the process and the procedure so that we can truly say to the entire world that the Philippines is a model when it comes to climate finance,” Borje told civil society leaders at the roundtable event.

“When I personally go out there and negotiate for unlocking of climate finance, we can tell them we are doing it in the Philippines with our limited resources, [therefore] you in the international community, developed countries have that moral obligation to do much, much better.”

Jemilah Mahmood

A humanitarian veteran from Malaysia

Dr Jemilah Mahmood has witnessed intense human suffering in her over 20 years working in disaster and war relief. So she sees the first-time inclusion of a health theme at COP28 as a “huge step forward” – given how global warming is already wrecking humanity’s collective well-being.

In the coming weeks, governments worldwide are expected to endorse two declarations, one on health, and the other on relief, recovery and peace. Both documents, drafted by summit host United Arab Emirates, will call for greater political will, along with more funding and collaboration.

“People in the health sector have been pushing very hard for years for a COP to include a health theme,” Dr Jemilah said.

“I think [the effort] is timely, because we are all just coming through a pandemic," she said, adding that the link between planetary damage and infectious diseases is now clear.

The 64-year-old, who founded the global humanitarian nonprofit Mercy Malaysia in response to the Kosovo war in 1999, and in recent years advocated for healthcare workers to focus more on climate change, also thinks the COP28 health declaration will need a stronger stance against coal, oil and gas – a late-October draft omits the term "fossil fuels" entirely.

“Unless we are really talking about reducing fossil fuels, then we are constantly going to be putting out fires,” Dr Jemilah said. She is one of over 30 signatories in an open letter by global health professionals asking for a phase-out of fossil fuels to be included in the declaration.

Dr Jemilah is the co-founder and executive director of the Sunway Centre for Planetary Health, a university think-tank that works at the intersection of public health and climate issues.

Key issues in Southeast Asia, she said, include preparing for more outbreaks of diseases such as dengue and malaria, stemming from climate shifts. Biodiversity loss is also causing food security issues, she added.

COP28 will be Dr Jemilah’s first time at the summit in-person. She will be speaking at the health, humanitarian and Malaysia pavilions. She anticipates “a bit of a circus” around the huge conference, but added that the focus must be on outcomes.

“Health workers are the most trusted people in the world and our voices must be stronger,” she said, adding that the sector needs to get better at understanding and communicating climate risks.

She also will be keeping a keen eye on the loss and damage funding negotiations, and how developed countries have been trying to avoid strong terms obligating payments, while paying homage to the recently deceased Bangladeshi scientist Saleemul Huq, widely regarded a pioneer of the global loss and damage movement.

“I ask myself, in today’s world, where is the global solidarity, to want for others what you want for ourselves?” Dr Jemilah said.

Her take-home message? “Everything we do now, no matter how small, will contribute to some change. We have no time to lose, with everything stacked against us. I think we just need to push on”.

Tual Sawn Khai

A solitary voice from Myanmar

Dr Tual Sawn Khai, 31, has seen his fair share of extreme weather. In 2015, nine million people were affected by flooding and landslides. Dr Khai’s home region, the mountainous Chin state, declared a state of emergency, and he was involved in rehabilitation and emergency response work for over six months.

“I’m a survivor, you can say,” Dr Khai, who is from the Zomi-Chin ethnic group, said of the experience.

Myanmar is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate risks – Cyclone Mocha killed 145 people and affected millions this year – but Dr Khai worries that the world is not caring enough about Myanmar's climate vulnerability, with public attention firmly on the nation’s civil war.

Since the military overthrew the elected government in 2021, there has been no official representation from Myanmar at COP summits. It is not clear if anyone will be present at COP28 either. Both the junta and exiled government are vying for recognition at the United Nations, and hostilities have recently flared.

Dr Khai, currently a researcher at the United Nations University in Malaysia, will be at COP28 with Mountain Sentinels, a United States-based nonprofit that champions the sustainability of mountain environments and communities worldwide. His research has been focused on climate, health and migration issues.

He will be speaking about how 3 billion people rely on mountain ecosystems for food, water and livelihoods, and how mountain communities are often marginalised, while their knowledge is key to climate adaptation.

A town in Myanmar's mountainous Chin state. Image: Wikimedia Commons/ Salai Tinaung.

A town in Myanmar's mountainous Chin state. Image: Wikimedia Commons/ Salai Tinaung.

Dr Khai will also be looking for opportunities to raise awareness of what has been happening in Myanmar. Extreme heat has been ruining crops, environmentally destructive mining has increased under the military administration, and desperate farmers are turning back to opium farming, Dr Khai said. For these reasons, he doesn’t want the junta to represent the country at COP28.

There is the issue of Myanmar’s dam-building ambitions too. There are 29 sizable hydropower dams in the country and dozens more are in the pipeline.

Dr Khai singled out the Myitsone Dam, a 6-gigawatt megaproject that will flood an area equalling 60 per cent the area of Singapore, as a project that needs to stop because of the environmental and social harm it will cause. Construction has been suspended for over 10 years, though there have been murmurs about it restarting.

“We need to raise awareness globally that this dam should never be built,” he said.

It will be Dr Khai’s first COP, an experience he is both excited and nervous about. He would also have attended COP26 in Glasgow in 2021 as a United Nations youth advocate, but couldn't get his visa approved in time.

Dr Khai has been making inquiries about compatriots attending COP28, but thus far hasn’t found any other Burmese organisations going. Ground-up environmental groups are rare in Myanmar, he said, and the civic space is getting narrower for non-government organisations because they need to register with the military government.

“I think I might be the only one [from Myanmar] there,” he concedes.

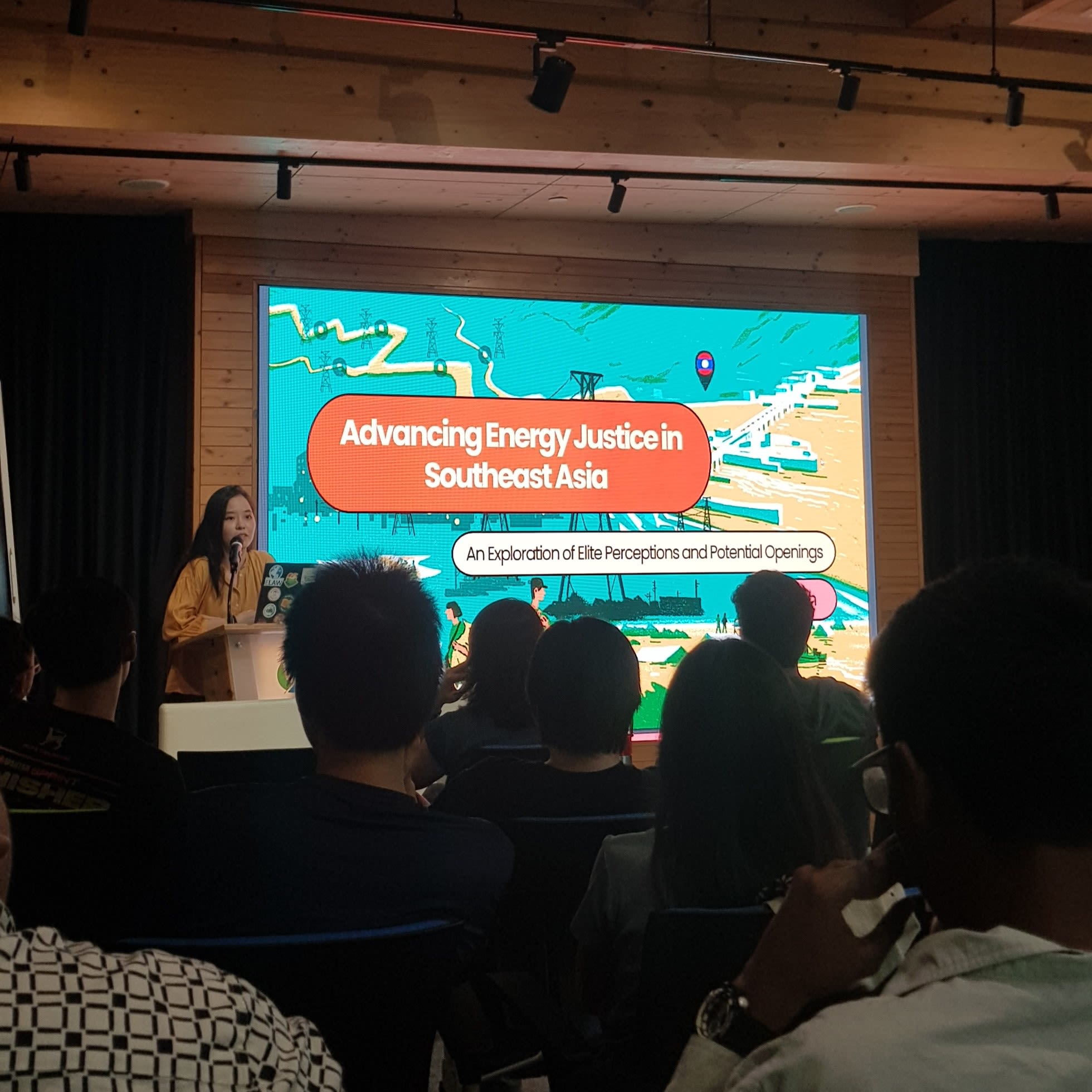

Ning Yiran

A youth advocate from Singapore

One of Ning Yiran’s most enduring impressions of a COP conference came from watching videos of policymakers moved to tears in 2015, when the Paris Agreement climate deal was adopted after days of intense negotiations.

But the 23-year-old felt conflicted when offered the chance to witness such negotiations up close at COP28. The opportunity came via a government climate programme, which will be sending 20 youths from the city-state to the summit.

For one, there is the issue of carbon emissions flying from Singapore to Dubai – 900 kilograms for a round trip. Ning has also been reflecting on what her presence at the summit will achieve, where she does not expect to have a platform to speak.

“I'm not sure if my participation will really make a difference to COP28,” Ning said.

It was ultimately the learning opportunity that convinced the youth advocate and environmental studies graduate from liberal arts college Yale-NUS to make the trip.

While in school, Ning worked with non-profit Advocates For Refugees to raise funds for a theatre group in Malaysia founded by displaced Afghans. She was part of a student movement that last year called for local universities to divest from fossil fuel firms.

Her undergraduate thesis examined how Southeast Asia’s renewables megaprojects, such as dams and solar farms, were displacing local communities. Some of these projects have attracted Singapore’s interest as potential sources from which to import low-carbon electricity. She found that while governments often talk about the economics and benefits of the green energy transition, local communities that are affected by renewables projects want to address issues such as climate justice and dignity.

Laos has been selling electricity from its many hydropower dams to neighbours and countries as far as Singapore, but development of the megadams also evicts riverine communities and hurts biodiversity. Image: Flickr/ WorldFish.

Laos has been selling electricity from its many hydropower dams to neighbours and countries as far as Singapore, but development of the megadams also evicts riverine communities and hurts biodiversity. Image: Flickr/ WorldFish.

“I want to attend COP28 to try to make sense of what I feel are two separate worlds that sometimes can end up in their own echo chamber,” Ning said.

Ning is also planning to share her experience at the summit through social media – “so that more people can feel excited, or frustrated, with us, and also benefit from the access and experiences we get to have”, she said.

She expects COP28 to be hectic and emotionally overwhelming, based on her friends’ experiences at last year’s COP27 where issues they cared about were sometimes dismissed by negotiators or caught up in power plays.

Meanwhile, Ning is keeping up with the latest developments. She has scrutinised United Nations climate reports, and tracked how loss and damage talks have been running overtime, with contentions in areas such as if the World Bank is fit to host a new fund.

She hopes to see the fund for helping vulnerable countries rebuild after extreme climate events fully address developing country concerns. There must also be agreement on a phaseout of unabated fossil fuels that leaves no one behind, she said.

“It is very easy to just go there and have a good time. But I want to go prepared, so that the spot I’m taking up is justified. I think that’s the pressure I’m putting on myself,” Ning added.

Hadi Prayitno

An Indigenous Peoples observer from Indonesia

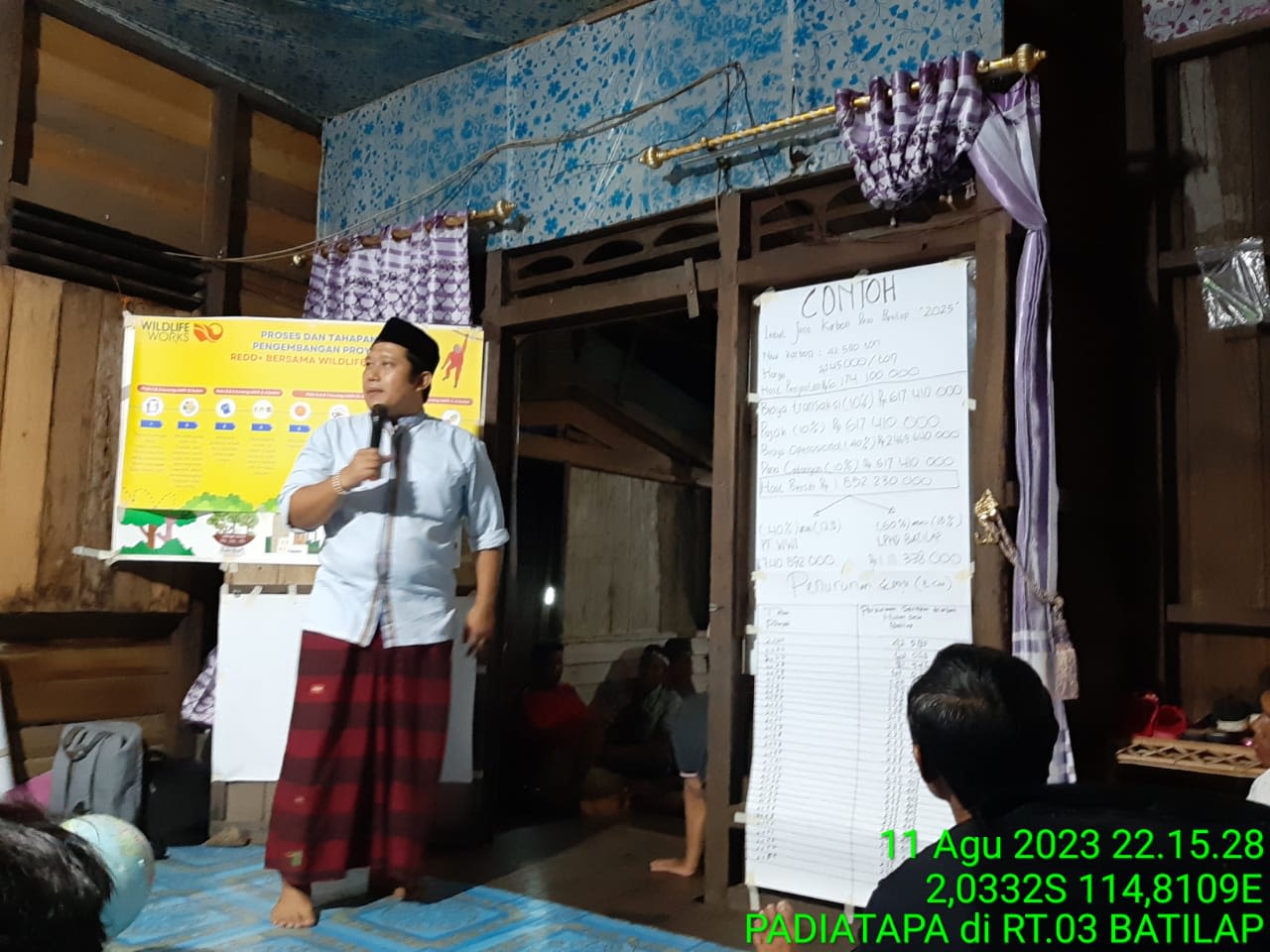

Hadi Prayitno has been working with communities, including Indigenous Peoples in Indonesia, for over two decades. But it is only now that he will be attending a conference that will tackle the rights of vulnerable groups at the same international level as the COP.

The 41 year-old is attending the world’s most important climate negotiations as the stakeholder engagement manager of United States-headquartered nonprofit Wildlife Works, which advocates for the voluntary carbon market as an effective and equitable financial mechanism to stop deforestation.

“I'm very excited and feeling lucky because the same opportunity is not provided to all people. I can learn many things from this event, even if my role is only as an observer,” Prayitno says.

Colleagues who attended previous conferences described to him how the Glasgow summit in 2021 was very grand, followed by a more understated event in Egypt last year.

He does not expect too much festivity for the one he is about to attend in Dubai, but what matters to him, he says, is the opportunity to learn and exchange experiences with countries similar to Indonesia which have some of the world’s biggest natural forests and communities of Indigenous Peoples, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo and Brazil.

"A successful negotiation will be when all parties declare loudly what they will do to respect the rights of Indigenous People and local communities," he said.