The corporate world recognises the need to take faster climate action, but is struggling with how to curb emissions to bring about a net zero future, business leaders said at the Ecosperity sustainability conference on Tuesday.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

“I’ve spoken to 250 chief executives who have made net-zero commitments. None of us has a clue how we’ll get there,” said Sunny Verghese, chief executive of agribusiness firm Olam, on a panel on decarbonisation at the event hosted by state investment firm Temasek.

Verghese, who is also chairman of the World Business Council on Sustainable Development (WBCSD), whose 200 member multinationals committed to reach net-zero by 2050 last year, said that climate action is “not about bold announcements — it’s about getting it done”. Companies need a playbook to help them meet carbon reduction targets, he said.

More than one fifth of the world’s biggest companies have made net-zero commitments so far this year, with more expected to make carbon-cutting declarations in the run-up to the COP26 climate negotiations in November.

The root of the problem is that the way carbon is measured is “not trusted or robust,” said Verghese. Olam emitted 78 million tonnes of carbon last year, but 95 per cent of the total came from indirect Scope 3 emissions that are hard to measure, Verghese shared.

“

Climate risk is going to reshape finance. It’s not going to be an evolution, but a revolution in how we think about finance.

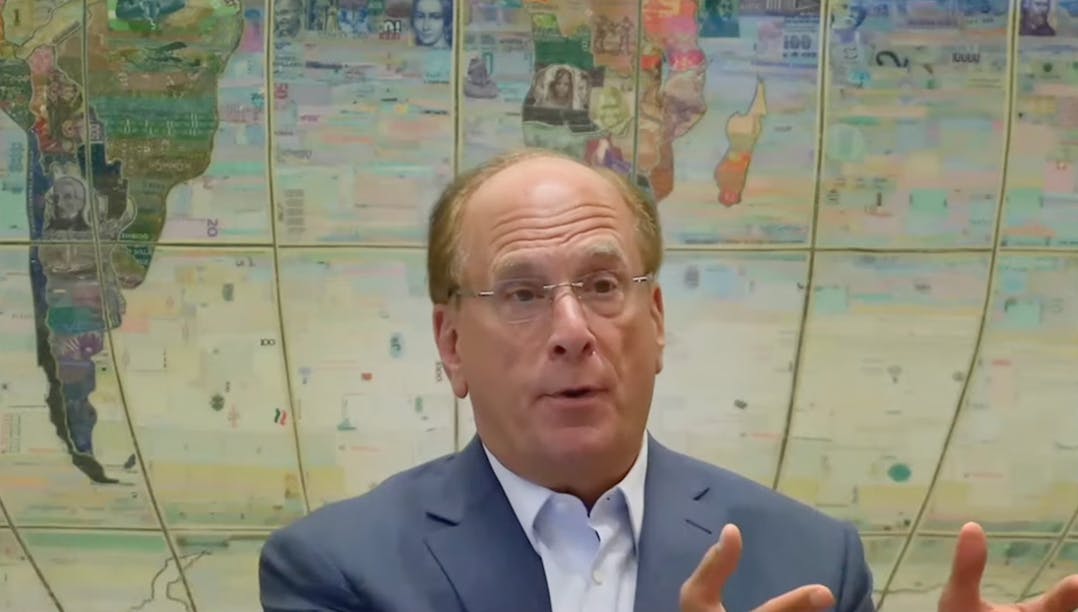

Larry Fink, chairman and CEO, BlackRock

“The granularity of the pathways [companies are taking to reach net zero] and how we’re going to get there is extremely flimsy, and does not give us confidence that we can meet these commitments,” he said.

Piyush Gupta, group CEO of DBS, Southeast Asia’s largest bank, shared his frustration with the “alphabet soup” of metrics for gauging sustainability performance, and a lack of clarity over which metric to use. “Two consultants will come to you with two different measures,” he noted.

Herry Cho, sustainability head, Singapore Exchange. Image: Temasek

Herry Cho, the newly appointed head of sustainability and sustainable finance at Singapore Exchange (SGX), acknowledged that navigating the complex language and landscape of decarbonisation can be a challenge for businesses in Asia, which is why SGX launched a guide for corporates on what actionable steps they can take earlier this year.

The various frameworks for measuring sustainability have been under pressure to merge to make life easier for disclosing businesses. New taxonomies for measuring green finance, such as the European Union’s Sustainable Finance Taxonomy and a coming rulebook for Southeast Asia, have been facing similar pressure.

Dr Ma Jun, chairman of the Green Finance Committee of China Society for Finance and Banking, said there was a “collective responsibility” for the finance industry and regulators to produce internationally consistent standards to help ensure a “just, affordable” transition to a low-carbon economy.

Getting the data right is critical for making carbon markets work, said Bill Winters, group chief executive of Standard Chartered Bank.

Voluntary carbon markets, which allow firms to offset their emissions by buying credits in projects that remove carbon from the atmosphere, have suffered from “uneven standards” and a lack of confidence in the integrity of credits, Winters said. This is evident in the price of carbon, which can range from $1 to $60 a tonne, he noted.

Carbon markets can reduce the carbon intensity of the economy and help companies achieve their net zero commitments, said Winters, who chairs the Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets (TSVCM), a private sector-led initiative working on a new governance framework to improve carbon markets.

“If we’re successful, we’ll take a fragmented market that cuts across geographies, project types and buyers and seller types, and bring consistency and coherence to this market, with a high level of integrity and transparency,” said Winters.

To cut global carbon emissions in half by 2030, and reach net-zero by 2050, to meet the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C target, action through voluntary carbon markets will need to grow 15-fold by 2030 and 100-fold by 2050 from 2020 levels, according to data from TSVCM.

Climate risk and inequality

Larry Fink, the chairman and CEO of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, was bullish on the role of the private sector in tackling climate change, saying that the “boldness” showed by corporates needed to be followed by governments ahead of the climate talks in Glasgow.

“We need boldness by governments, not just boldness by a couple of CEOs, because we know our power to move the [climate] curve is very small,” he said.

His comments echo a call from investors and companies worth US$2.4 trillion made in June for governments to draw up clearer policies that align countries with the Paris climate accord.

Larry Fink, chairman and CEO of BlackRock, speaking at Ecosperity Week 2021. Image: Temasek

Fink, who declared earlier this year that a “tectonic shift” in finance had shifted sustainability mainstream, said that governments should not rely on publicly listed firms to take climate action, as this would be “asking large companies to be the climate police — and that’s not our role.”

Leaving the heavy-lifting in carbon reduction to public firms could lead to “bad unintended consequences”, Fink said, adding that this was his biggest fear ahead of COP26.

Public firms are starting to sell off high-carbon assets to private firms to improve their carbon profiles, with no net benefit in reducing the world’s carbon footprint, he explained.

“Are public companies going to be able to do it [decarbonise society] themselves? The answer is no,” said Fink. “We need to get all of society on board and move carefully together.”

He warned that the energy transition would lead to inequality between the industrialised and emerging economies, which are taking climate action at different speeds.

“As we manage climate risk, we are going to create even more inequalities between developed and developing countries, and we’re going to create more inequalities within society,” he said.

“We can mitigate much of this if governments come up with a comprehensive plan together,” said Fink.