A new wave of greenwashing is emerging that will give regulators in Asia still trying to figure out how to police misleading or bogus sustainability claims a fresh set of problems to navigate.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Newly launched guidelines for how Asian financiers can avoid greenwashing identified a medley of emerging forms of malpractice in how companies report their sustainability progress, including the over-use of carbon offsets by companies claiming to be “carbon neutral” without first reducing their emissions.

Speaking on a panel to launch the guide, Herry Cho, group head of sustainability and sustainable finance at Singapore Exchange (SGX), said that greenwashing can have a “devastating effect” on the financial markets, especially given the relative nascency of climate finance in Asia.

“If unchecked, it will represent long-term risks and will impede progress by preventing effective resource allocation for impactful climate action – and in the short term, a loss of public trust,” she said.

Another emerging trend is companies accusing their competitors of using fudged green claims to outdo their own sustainability brand positioning, the report by environmental law charity ClientEarth and Asia Investor Group on Climate Change found.

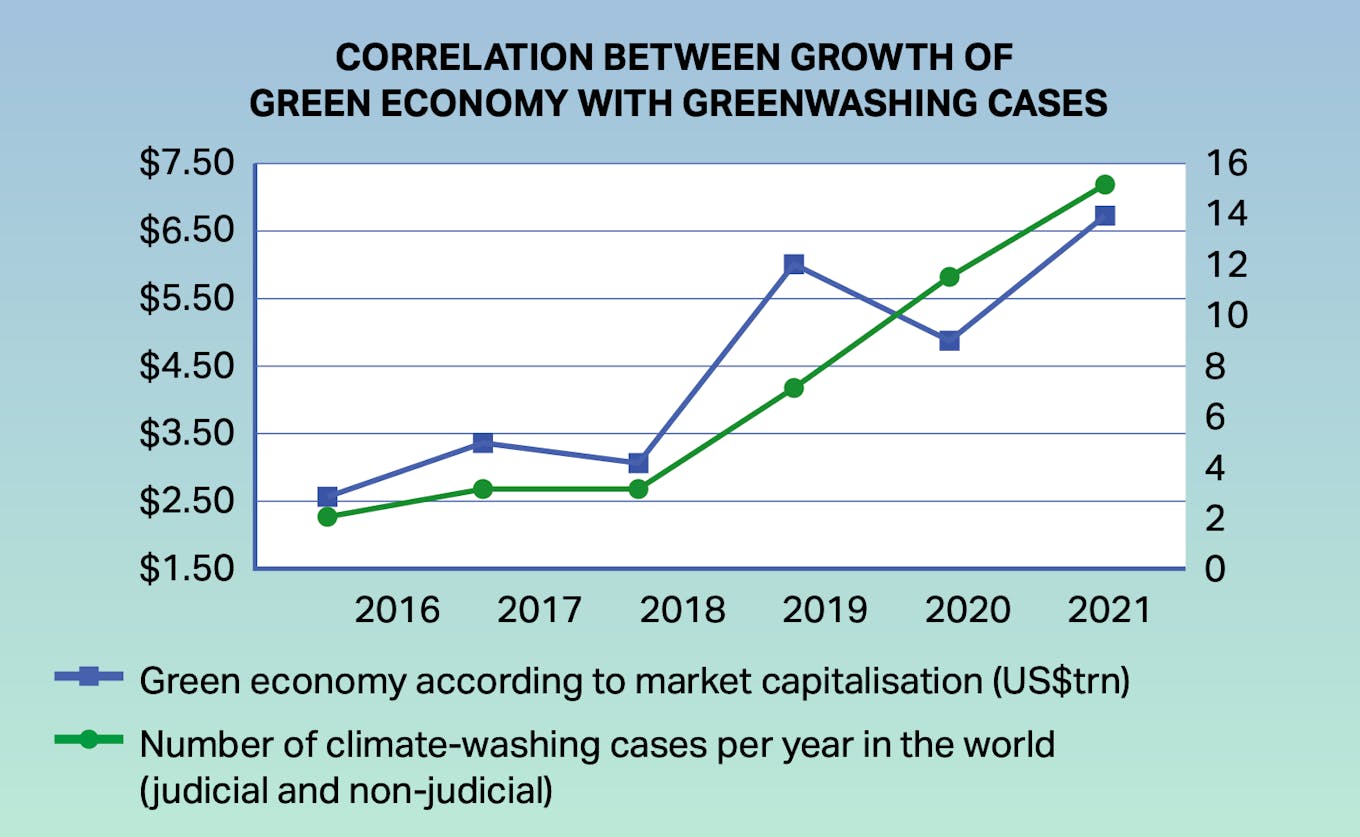

The size of the global green economy growing alongside the number of climate-washing cases between 2016-2021 [Click to enlarge] Sources: Climate Social Science Network, FTSE Russell, Greenwashing and how to avoid it

A less obvious new variant is greenwashing by association, when asset managers include companies in their green portfolios based on that firm’s greenwashing, and present their portfolios as sustainable to investors. This type of greenwashing also includes firms that have joined net-zero alliances but do not meet their commitments, or those that fund organisations which lobby against climate goals.

Arguably the biggest cause for concern is “transition-washing”, when companies provide so-called green finance to bankroll carbon-intensive firms that do not use the capital to pivot their business models away from fossil fuels, or only use the funds to transition in certain jurisdictions – a problem when firms only invest in the green transition in countries where regulations squeeze carbon-intensive finance.

The main problem is that there is no clear definition of what green is, what ESG is, or what defines sustainability.

Elaine Ng, associate director, international affairs and sustainable finance, Securities and Futures Commission, Government of Hong Kong

Regulation is not enough

The prevalence of greenwashing has ballooned in tandem with a market appetite for environmentally sustainable financial products that has soared since the Covid-19 pandemic.

From 2016 to 2021, the market for environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing has grown by an average compounded annual growth rate of 27 per cent in global assets under management (AUM), according to data from professional services firm KPMG, as have incidences of firms accused of greenwash – albeit mainly in the West.

Asia – which has experienced the slowest growth in ESG investing outside of Japan, with just 2 per cent growth between 2019 and 2021 – has been relatively slow to legislate against greenwashing. However, territories including Japan, Singapore, Hong Kong, Australia and South Korea have started to tighten rules for how companies disclose their environmental impact.

Speaking on the panel to launch the guide, Sean Tseng, a legal consultant at ClientEarth and co-author of the guide, said that regulation to grapple with greenwashing is difficult, because it involves trying to “control an ever-evolving and amorphous problem.”

Relying on what companies are telling investors in sustainability reports is risky, and efforts to mandate companies to disclose their climate impact since 2016 “unfortunately haven’t addressed greenwashing sufficiently,” Tseng said.

Asia is a patchwork of approaches to sustainability disclosure. Malaysia has mandated ESG reporting for all listed firms since 2016. South Korea is maintaining voluntary disclosure until at least 2025.

Companies in Asia may be particularly prone to sustainability overclaims, as the region is pursuing ambitious economic growth while at the same facing international pressure to decarbonise, said David Smith, senior investment director, Asia Pacific, at Abrdn, an asset management firm.

Southeast Asian ride-hailing firms Grab and GoTo and Indonesian steel maker Gunung Raja Paksi have spoken of the difficulty in setting credible decarbonisation targets that stand up to scrutiny while chasing heady business growth targets.

Smith said that while regulators “set the tone” for the finance industry with frameworks and expectation-setting, asset managers should recognise that regulators “can’t do it all” and need to “roll up our sleeves” to better interrogate the environmental claims firms are making.

“Even if there’s a disclosure that looks as though it’s gone through a [due diligence] process, we can’t assume that regulators have looked at everything in every annual report. We can’t take it at face value.”

Smith said that some greenwashing is “terrifically easy to spot”, particularly around the claims companies make about how well aligned they are with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), sustainability targets the United Nations has set for the world to meet by 2030.

“Some firms are claiming alignment with every single SDG,” he said.

What does green mean?

Smith noted that a considerable amount of greenwashing is unintended and is not the result of a company or individual “trying to pull the wool over investors’ eyes.”

Finance executives can find themselves accidentally greenwashing because of the shifting landscape for what constitutes greenwash and the myriad sustainability reporting frameworks designed to mitigate the problem.

Elaine Ng, associate director, international affairs and sustainable finance, for the Securities and Futures Commission for the government of Hong Kong, said the main problem with tackling greenwashing is that “there is no clear definition on what green is, what ESG is, or what defines sustainability.”

How to avoid greenwashing in finance

○ “Screen your green”. The accuracy and credibility of any green statement must be scrutinised.

○ “In good and green faith”. Be transparent about how green objectives are integrated into the financial product and/or its financial objective.

○ “Walk your green talk”. Ensure the firm or fund’s green image is consistent with the internal actions of the company or fund and their actions in relation to third parties.

○ Observe the changing shades of green. Expectations and regulations are fast evolving, so monitor developments in relevant jurisdictions.

○ Be alert to green duties. Know your legal and fiduciary duties to investors, beneficiaries and stakeholders.

Source: Greenwashing and how to avoid it: An introductory guide for Asia’s finance industry

Sophia Cheng, chief investment officer of Cathay Financial Holdings, Taiwan’s biggest financial group, welcomed moves to harmonise sustainability frameworks to bring greater clarity to ESG reporting and reduce greenwashing risk.

Next month, the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), which was formed after the COP26 climate talks in 2021 to create comparable disclosure standards, is set to introduce a global baseline for climate reporting which is expected to be widely incorporated into disclosure requirements globally.

Cheng noted that are challenges for implementing harmonised frameworks in Asia, a region at different stages of economic development with a range of national climate commitments that nudge businesses towards reliable disclosure at different speeds.

Competition between territories in the region, for instance the rivalry of Singapore and Hong Kong as regional green finance centres, is likely to push Asia towards progress in sustainability standard-setting and minimising greenwashing, she said.

Regulators need the right tools to be able to understand where greenwashing is happening, and “teeth” to properly enforce their regulatory frameworks, Cheng noted.

Punishment for greenwashing firms has been all but absent in Asia to date, with only South Korea declaring that it would fine companies found guilty – albeit with penalties (a maximum of US$2,300) unlikely to deter large polluters from making iffy green claims.

While regulators tighten the rules for ESG claims, non-government organisations are taking the lead in policing greenwashing. The act of filing a legal claim against a company sends a “signal” that can drive change through the market, said Zoe Bush from the Environmental Defenders Office.

NGOs are now focusing their work on how well aligned companies’ businesses models are with climate goals rather than how well prepared they say they are for the energy transition, said Bush.

“It’s not in anyone’s interests to penalise genuine transition efforts. So we’ll see more of a focus [from NGOs] on corporate alignment with the energy transition. And we’ll see more focus on the laggards rather than the leaders,” she said.