To most, irrigation is an invisible miracle that keeps our crops growing. For the Australian farmers who produce almost 93 per cent of the country’s daily domestic food supply, irrigation is a lifeline. But drought has pushed irrigation up Australia’s national agenda as farmers feel the effects of climate change.

The biannual Irrigation Australia International Conference and Exhibition was sold out in its last iteration, and this year, how to sustainably irrigate Australia’s water scarce arable lands is leading the debate.

Population growth and water stress in Murray Darling Basin are viewed as a double challenge to be addressed by stakeholders at the Exhibition. Murray Irrigation’s chief executive officer Michael Renehan has a vision for Australia’s irrigation systems to become fully automated. What does this mean for Australia’s farmers, and how can irrigation become sustainable?

“

Sustainable irrigation—targeting future water security—cannot be done in isolation. It is important to consider its interaction with other sustainable development goals.

Dr Jing Liu, agronomist, Purdue University

Sustainable irrigation: past and future

The Mulwala Canal is to Australia what the Nile is to Egypt. As Australia’s largest canal, the Mulwala has a storage capacity of 117,500 mega litres, or one quarter of the Sydney Harbour. Red gum forest was cleared in the 1930s to make way for the canal which was completed in 1942. The destructive impacts of large-scale, man-made waterways set a precedent for finding ways to irrigate sustainably.

Irrigation is already being revolutionised by technologies like internet of things (IoT) and satellite climate data to measure soil nutrient conditions, moisture content, and optimise water flows and efficiency. With increasing water scarcity, irrigation must do more with less.

That’s why Renehan envisions fully automated irrigation systems with customers self-servicing at automatic and remote-controlled water outlets.

In an interview with Eco-Business, Renehan says: “There will also be a shift in labour and skill sets as businesses become leaner as technology drives further efficiencies.” Experts agree that fixing leaks and using smart metering can shoot canal irrigation water efficiency up from 33 per cent to 90 per cent in developed countries.

However, research shows that engaging farmers to better manage irrigation infrastructure holds more promise for the long-term adoption of sustainable farming practices. If irrigation is to be fully automated, to what extent can farmers stay engaged?

The risks and distribution of ownership within a fully automated irrigation system are unclear. It is also hard to determine how much more irrigation can be sustainable even with optimised systems when dealing with a scarce, finite resource like water.

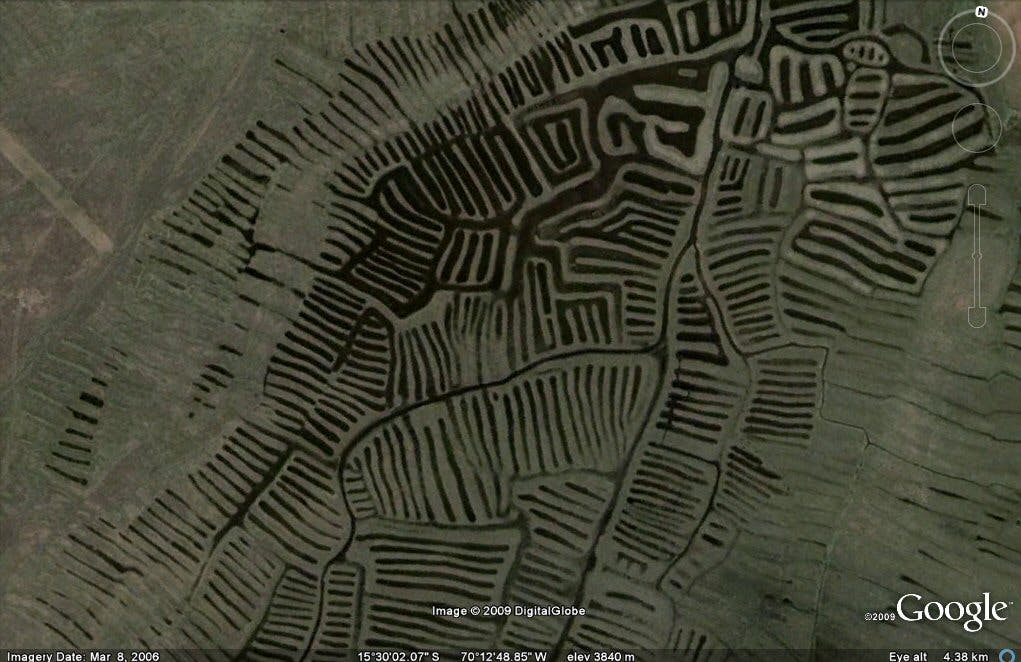

Water scarcity is an age-old issue that ancient civilisations have faced throughout time. These civilisations may hold some insights into sustainable irrigation. The iconic terraced rice fields in Banaue, Philippines have been carefully cultivated and irrigated for over 2,000 years. In other regions like India, Kenya, and Peru, age-old irrigation techniques are being revitalised and adapted to modern needs.

In Peru, suqakollos or waru-warus are patterned systems of raised cropland and water-filled trenches dating around 8,000 years old. Image: Google Earth

Non-government organisations like Natural Heritage First in India and the Africa Sand Dam Foundation (ASDF) in Kenya have been pushing the potential in applying traditional practices to contemporary issues. In Peru, the suqakollos project is funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) trust fund as one of several globally important agricultural heritage systems (GIAHS).

In many developing countries, dams and canals continue to be fetishised as symbols of development without taking into account biodiveristy loss, or the estimated 80 million people that have been displaced worldwide by dams, says Fiona McAlpine, communication manager of The Borneo Project.

As a developed country, Australia’s irrigation future can take past examples of ancient irrigation in tandem with the destructive recent past of hydro-projects in other countries to truly do more with less.

Beyond water-smart

A range of strategies for sustainable irrigation will converge at the Irrigation Australia International Conference and Exhibition. Dr Chantal Donnelly, head of water resource modelling at the Bureau of Meteorology, says that his organisation’s strategy is to focus on developing partnerships with irrigators on the ground. Working closely with agronomy specialists presents other avenues for innovation, she says.

Very much on the ground level are micro-irrigation systems (MIS).The market for MIS is growing at 40 per cent annually in India, one of the world’s largest farming nations, with enormous opportunity for business development and promising potential for the livelihood of farmers in Australia, too.

Combining the elements of sun and water is another encouraging path for irrigation. Solar energy entrepreneurs have created business models for solar irrigation in places like Ethiopia, India, Kenya, Myanmar, and Latin America.

Irrigation and the Sustainable Development Goals

Pursuing sustainable irrigation cannot be done separately from other development and environmental goals, cautions agronomist Dr Jing Liu of Purdue University in the US.

Research shows that higher food prices and cropland expansion will accelerate aggressive irrigation use. Liu, the lead author of the global study, says: “Our findings show that pursuing sustainable irrigation—targeting future water security—cannot be done in isolation. It is important to consider its interaction with other sustainable development goals.”

By zooming in on just water, other fluctuations in the environment like soil nutrients may be ignored, leading to inaccurate projections of local water demand and supply.

Dr Liu urges: “It’s also crucial to distinguish between sustainable irrigation and the overall conservation of the irrigated land. To ensure food security, irrigation should be encouraged wherever and whenever it is environmentally sustainable, so the key is to improve the spatial and temporal allocation of water used for irrigation.”

What do farmers need?

Irrigation policy must be considered alongside other elements including institutional and legal transparency, research and development, and ecosystems management, says Richard Munang, Africa regional climate change coordinator of United Nations Environment Programme, Kenya.

“I think what needs to be done is ensure that water-use policies should be developed within a broader framework that promotes agricultural growth through profitable investment,” he says.

In February 2016, Murray Irrigation struck a deal with Snowy Hydro to make up to 200 giga litres—or 200 billion litres—of water available as an advance to Murray Irrigation for the 2016/17 irrigation season. The offer was met with a “lukewarm response” that Renehan attributes to coincidental heavy rains. Only around two thirds of eligible farmers took up Snowy Hydro’s offer.

Snowy Hydro’s unsuccessful bid shows how better accounting for variations in weather will help to design viable and effective irrigation systems over the long-term.

Borrowing schemes and fully automated irrigation systems are just a few of the many options that will be up for discussion at the event. Even facing water scarcity, Australia has no shortage of opportunities to bring together private companies, government, and civil society to ensure a sustainable future for irrigation.

The 2018 Irrigation Australia International Conference and Exhibition will be held at the new International Convention Centre in Sydney, 13-15 June.