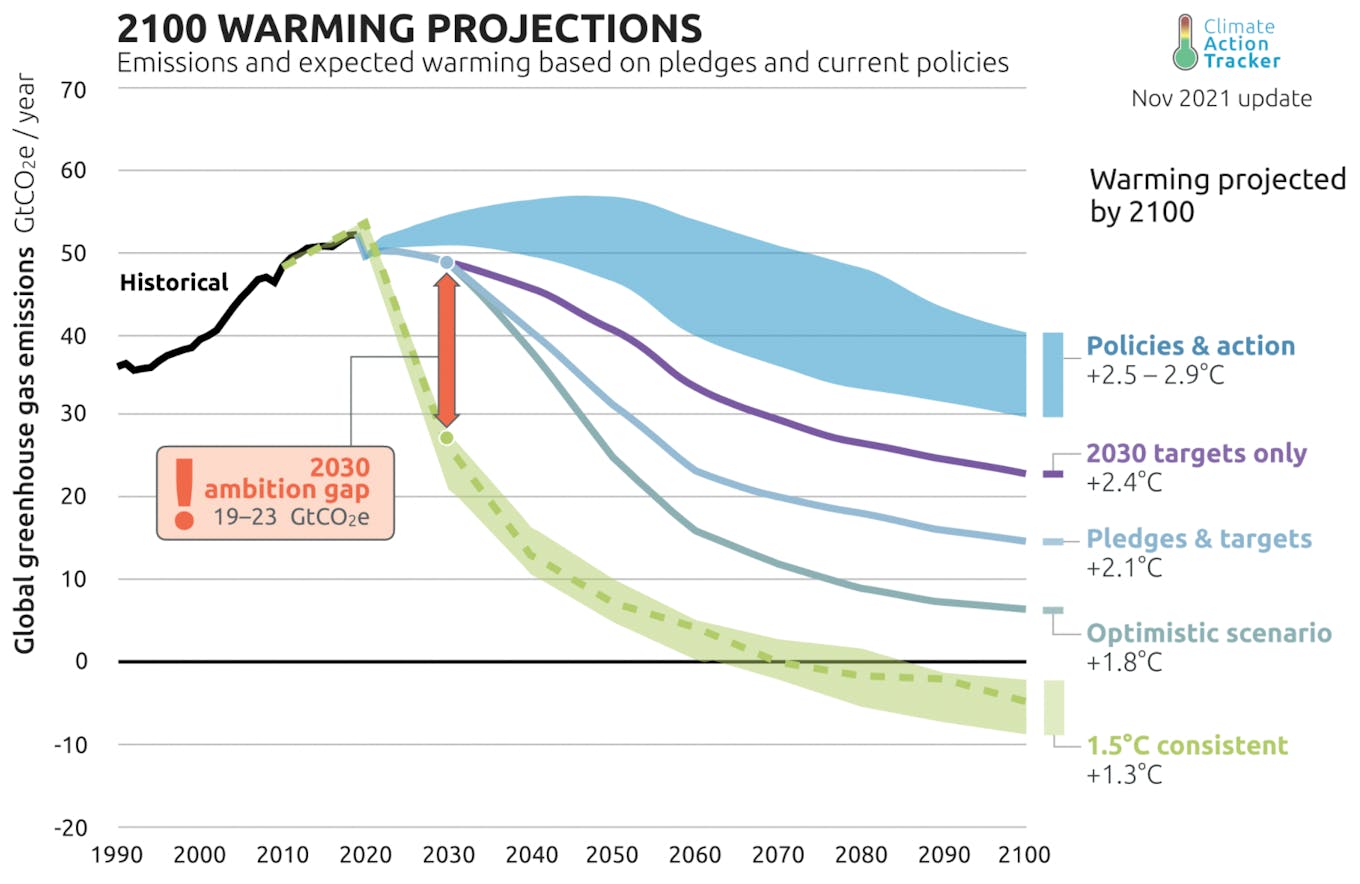

The world is on course to heat by a ruinous 2.4 degrees Celsius by the end of the century, according to a climate prediction model based on current national pledges to rein in greenhouse gas emissions.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

A study by Climate Action Tracker (CAT), published on 9 November, finds that if countries successfully meet the net-zero emissions commitments they have made by 2030, global average temperatures will increase by between 1.9°C and 3.0°C — which averages at 2.4°C — above pre-industrial times by 2100.

Countries were urged to commit to net-zero emissions by 2050 at the United Nations’ (UN) COP26 climate talks in Glasgow, by accelerating the phase-out of coal, ending deforestation, investing in renewable energy, and speeding up the switch to electric vehicles, but the UN has warned that updated national pledges to reduce emissions still fall short.

More than 2°C of global heating could mean that one billion people endure life-threatening heat waves, coral reefs that sustain fisheries are wiped out, violent storms become common, and cities face two metres of sea-level rise if ice sheets collapse, climate scientist Benjamin Horton, director of the Earth Observatory of Singapore and a professor at the Asian School of the Environment in Nanyang Technological University, told Eco-Business.

Most of the world’s nations agreed in Paris in 2015 to try to cap global warming to “well below” 2°C and to “pursue efforts” towards 1.5°C, but only one country — the small, forested West African nation of Gambia — is on an emissions path aligned with the Paris Agreement, a study by Climate Action Tracker found in September.

A flurry of commitments from countries to reach net-zero emissions — including India by 2070, China by 2060, Indonesia by 2060, and Japan by 2050 — over the past year have brought the world only 15 per cent closer to meeting the 1.5°C target, CAT’s analysis shows. When the Paris Agreement was signed, the world was on track for 2.7°C of warming.

“

COP26 has merely succeeded in candy-coating the appalling lack of concrete actions [to tackle climate change].

Yeb Saño, executive director, Southeast Asia, Greenpeace, and former climate negotiator

CAT’s prediction is gloomier than analysis by the International Energy Agency (IEA), a thinktank, which claimed that COP26 climate pledges could cap century-end global warming at 1.8°C. But IEA’s research assumes that countries would deliver on 2030 pledges, and nations that said they would reach net-zero by 2050 would actually do so.

CAT has pointed out that countries with ambitious targets are not on track to hit them, most lack concrete detail on how they will decarbonise, while others have resisted calls to bring forward their commitments to 2030 — the year the world must half emissions if it is to achieve the Paris Agreement 1.5°C warming limit goal.

If current commitments to reduce emissions are met, the world is on course for an average of 2.4°C of warming by the end of the century. Source: Climate Action Tracker.

To achieve a 1.5°C world, all fossil fuels subsidies should be stopped immediately, commented J. Sarvaiya, a former PwC decarbonisation and climate risk expert who joined the American Bureau of Shipping in March. Subsidies for fossil fuels, the burning of which is the biggest single driver of climate change, keep dirty energy artificially competitive with clean energy.

World leaders in Glasgow agreed to “phase down” coal use and fossil fuel subsidies, based on a last-minute objection made by coal-dependent India, to phase out the fossil fuel completely. Negotiations at the COP26 climate talks have “singled out coal but kept quiet about oil and natural gas,” Sarvaiya told Eco-Business.

“The commitments made at COP26 are still inadequate,” said Sarvaiya, who pointed out that global spending on the military rose to almost US$2 trillion last year, while only US$100 billion per year has been promised for climate funding to help developing countries mitigate and adapt to climate change. Environmental campaign group Greenpeace said the Glasgow Climate Pact “failed” to ramp-up climate financing from rich countries to help developing countries adapt to, and mitigate against the worst impacts of climate change.

“It’s not good enough, and COP26 has merely succeeded in candy-coating the appalling lack of concrete actions. Communities at the frontline of the climate crisis, including our youth, should be deeply concerned with this poor excuse of an outcome,” Greenpeace Southeast Asia’s Manila-based executive director Yeb Saño, a former climate negotiator for the Philippines, said.