When the Philippines’ main island of Luzon was placed under lockdown on 16 March to contain the spread of the coronavirus, roads to and from Metro Manila were sealed off, including farmers’ routes to the capital city.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

As the government scrambled to put together rules for food supply trucks to enter the city, Sonny Reyes found himself unable to deliver the 15,000 pineapples he had just harvested on his farm in Tanay, Rizal, about 60 kilometres from the capital.

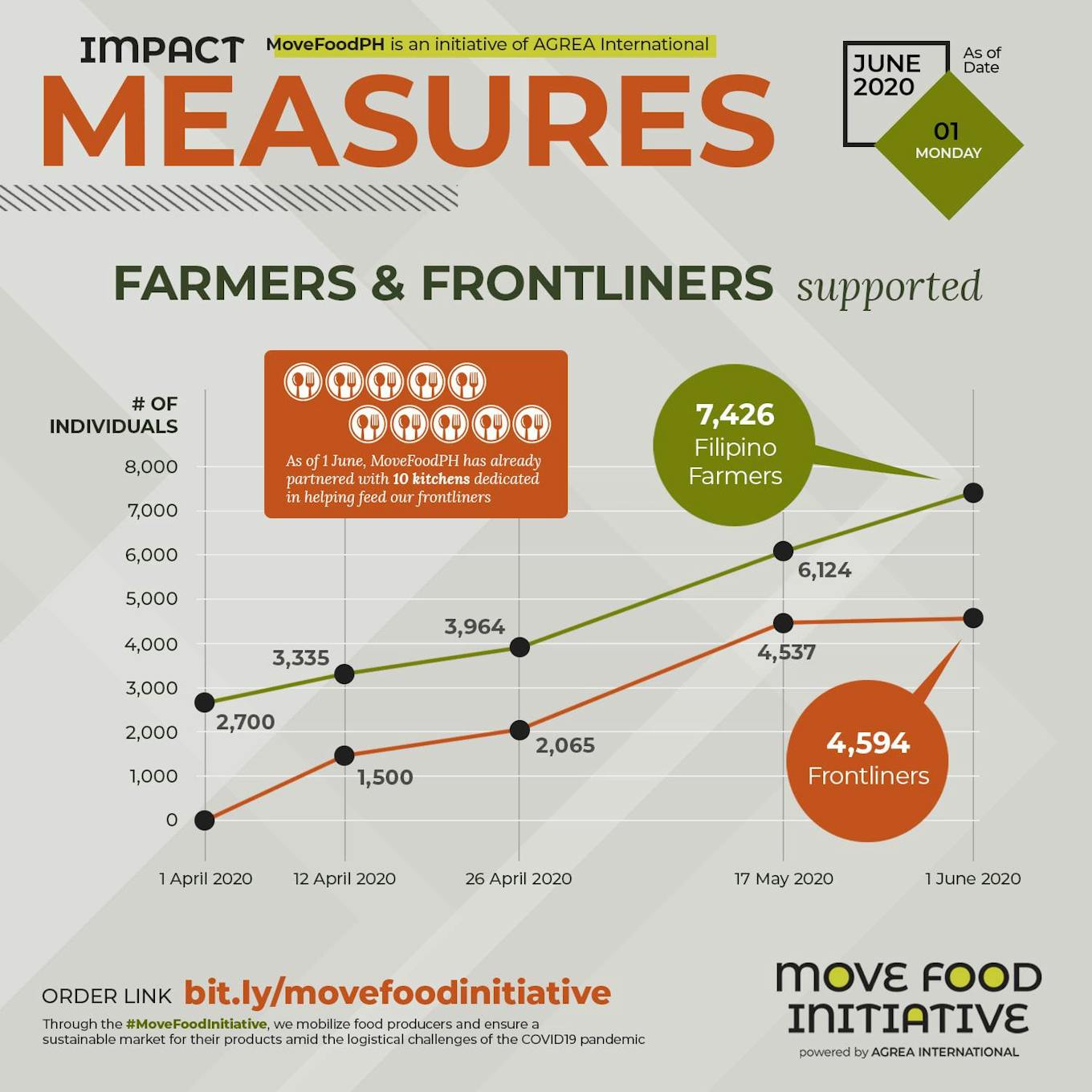

As of 1 June, the Move Food Initiative has delivered 160,190 kilogrammes of vegetables and fruits, supported 7,426 Filipino farmers, and partnered with and donated to 10 community kitchens feeding 4,594 front-liners. Image: Agrea

The 49-year-old had taken a loan of US$3,000 from the bank to be able to plant the fruits in time for the summer season. “If I didn’t sell the pineapples right away, they would spoil and I would have to throw them out. I would not be able to pay the loan and I would not have money to give my kids for school,” he told Eco-Business.

Reyes reached out to Cherrie Atilano, founder of non-governmental organisation (NGO) Agrea, for help.

Atilano—whose NGO aims to eradicate poverty among farmers and fishermen through training and education—helped him to source a truck owned by the Tanay municipal government that could easily pass through the stringent checkpoints and transport the pineapples to Makati City, where she lived.

In just three days, Atilano sold 3,500 pineapples. This sparked the idea for an online platform where consumers could order food directly from farmers and get them delivered to their homes.

Called the Move Food Initiative, Atilano and her team bought produce from farmers and sold it to consumers, strictly observing the government’s price freeze on the cost of basic goods for 60 days.

“

If we were able to have this much impact during a time when it was hardest to do business, what more after lockdown? The past months have shown us that we can be a player in this farm-to-table model.

Cherrie Atilano, founder, Agrea

As of 1 June, the day the Philippines began lifting lockdown measures, the initiative has shipped over 160,000 kilogrammes of fruit and vegetables from more than 7,400 farmers to nearly 52,000 families.

Atilano said the Move Food Initiative will continue as it pivots to become Agrea’s trading arm in Metro Manila.

“If we were able to have this much impact during a time when it was hardest to do business, what more after lockdown? The past months have shown us that we can be a player in this farm-to-table model,” she said.

The ‘Vegetable on Wheels’ programme is a rolling store that goes to all 36 barangays or villages in Iriga City, to support both the households and the farmers during the Covid-19 pandemic. Image: Iriga City Official Facebook Page

Meanwhile, in Iriga City in Bicol, southern Luzon, a truck loaded with essential goods such as rice, eggs, dried fish, onions and vegetables has served as a mobile store for over 100,000 of its residents during the two-month quarantine period.

Like Agrea’s food supply scheme, the Iriga city government bought produce directly from farmers, enabling them to sell food that would have otherwise have been dumped.

Dubbed Vegetable on Wheels, it was the first localised supply chain plan initiated by a Philippine city. The programme was soon adopted by larger metropolises like central business district Makati City, Baguio City, and Catbalogan City.

The department of agriculture came up with a similar scheme for cities that did not have such a programme. It got more stalls and mobile stores around the country on board, and went operational in early April.

From March to the end of May, the department reported that cities around the country which utilised mobile market programmes have procured more than US$40 million worth of produce directly from farmers. This helped the latter to stay afloat while ensuring food security for consumers.

“We will continue to help farmers even after the lockdown by increasing trading posts in strategic provinces in the country, where we eliminate the middleman so that farmers can directly bring their produce into food markets in Metro Manila,” said agriculture secretary William Dar in a webinar.

Residents in a city in Caraga, Mindanao practice social distancing as they line up to buy produce from a mobile market under the department of agriculture’s farm-to-table ‘Kadiwa’ programme. Image: Department of Agriculture-Caraga Facebook Page

Government intervention is important in exceptional times, but…

Food systems experts told Eco-Business that amid pandemic movement curbs, efforts by the government and other organisations to localise food supply chains helped prevent food waste and feed families that might otherwise have gone hungry.

In other countries, governments have also stepped in to support farmers and reduce the staggering amounts of food loss resulting from abrupt closures of restaurants and schools, which tend to order in bulk.

As supply chain players struggled with movement restrictions and to adapt quickly enough to cater to the surge in demand from supermarkets and individual households, the authorities have helped to ease the choke points. In Singapore, this meant keeping cross-border supply chains open, while in the United States, this meant buying surplus food from distributors for food banks.

“

Food security is a function of not just of the department of agriculture or local government units. It needs all government agencies to come together for an integrative food supply chain programme.

Domingo Angeles, professor and chairman, University of the Philippines Los Baños interdisciplinary studies on food security

At the height of the Philippines’ lockdown, restrictions in some provinces meant fruit and vegetable farmers could not even go into their fields to pick crops. And although trucks were available, drivers were staying at home. Poultry farmers complained that they found it difficult to supply chicken to Metro Manila as some local government units have set up roadblocks and personnel restrictions that have affected their deliveries and supply chains. The meat industry warned of a severe shortage of supply by April, as the lockdown disrupted deliveries and production.

Farmers and fishermen in the Philippines lost about US$3.6 million in income, as they were unable to market 35 per cent of their produce, reported a study conducted by the country’s socioeconomic planning body, the National Economic and Development Authority.

Around 4.2 million Filipino families also experienced involuntary hunger in the three months of the outbreak, according to a survey from polling institution Social Weather Stations. The number of hungry Filipinos nearly doubled.

“During those exceptional times, the government needed to step up and it did,” said Bruce Tolentino, former deputy general of the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), an agricultural research and training organisation based in Los Baños, Laguna in the Philippines.

“In the lockdown period, with checkpoints in place and marketing chains like aggregators, traders, wholesalers and retailers facing labour shortages and related logistical difficulties, it made sense for government agencies and local governments to connect producers with consumers.”

Better policies, infrastructure needed in the longer term

But in the longer run, experts said governments should not be in the business of buying food. Instead, their role in shoring up food resilience is to build the necessary infrastructure and set the right policies.

“Food security is a function of not just of the department of agriculture or local government units. It needs all government agencies to come together for an integrative food supply chain programme,” said Domingo Angeles, professor and chairman of the University of the Philippines Los Baños’ interdisciplinary studies on food security.

Agencies responsible for energy, transport, nutrition, information technology and defence are also needed to ensure the smooth supply of produce, including in conflict areas, noted Angeles.

Under normal circumstances, it is best to leave the buying of produce and the supply of food to consumers to the private sector, as the scheme will be much too “expensive” for city governments in the long term, said Tolentino.

“

Farmers don’t need subsidies or dole-outs. They need these technologies which are all available in IRRI, but the Philippines, sadly, is not taking advantage of it. Instead, our other Asian neighbours are.

Bruce Tolentino, former deputy general, International Rice Research Institute

Removing the middleman does not necessarily mean farmers get the best prices for their goods, he said. Instead, the key is to give farmers greater access to the market—proper infrastructure and telecommunications systems can help farmers to reduce the cost of fuel, seeds, labour, fertiliser and pesticides.

“Even after Covid-19, if these logistics (issues) are not solved then there will continue to be price issues in Metro Manila and other consuming areas. Delays will cause food to spoil and farmers will continue to be unable to get best prices for their products,” said Tolentino, who is now part of the Philippine central bank’s monetary board.

IRRI executives give Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi a demonstration of drone technology in agriculture. This modern management practice, which increases rice supply by using GPS technology to plot and spray the fields, has been adopted by the Indian government. Image: IRRI

Investment in agricultural research and development in the country is grossly lacking—for instance, innovations that would lead to more drought-resistant and high-yielding crops, and those able to grow in less fertile and more water-stressed areas are badly needed, he said.

The Philippines became the world’s biggest rice importer in 2019 with purchases estimated at a record 2.9 million tonnes.

Food prices in the archipelagic country are not competitive because public goods like transport, science and technology have not been provided, and this became “very apparent in the Covid period”, Tolentino said.

“Farmers don’t need subsidies or dole-outs. They need these technologies which are all available in IRRI, but the Philippines, sadly, is not taking advantage of it. Instead, our other Asian neighbours are,” said Tolentino.