Nature-based solutions are proven ways of reducing carbon emissions and capturing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through the protection, restoration and management of natural ecosystems.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The mitigation potential of these solutions ranges from the protection of old-growth tropical forests, to sustainable forest management and regrowing native cover on degraded lands.

Altogether, these solutions can reduce up to 11 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide annually, and provide over a third of cost-effective climate mitigation that is needed worldwide to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 and keep global warming below 2°C.

According to a recent report, the current investments in nature-based solutions globally amount to US$133 billion, but this figure needs to triple by 2030 if the world is to meet its climate change, biodiversity and land degradation targets. The majority of current investments are from public funds (86 per cent), which poses a huge opportunity for private sector investment.

For businesses and investors, especially for those with risks in their supply chain linked to deforestation and land-use change, or those that seek cost-effective investment options to meet their climate commitments and targets, nature-based solutions present a substantial opportunity.

Businesses are increasingly interested in nature-based carbon credits as a way to offset their own carbon emissions, and as a new type of commodity for investment and trade. A carbon credit represents the avoidance or removal of greenhouse gases equivalent to one tonne of carbon dioxide.

Nature-based carbon credits are gaining attention as a credible mitigation option, and have surpassed the value of renewable energy credits. “The market price of nature-based carbon credits is now three times that of renewable energy credits in the voluntary carbon marketplace,” said Koh Lian Pin, director of the NUS Centre for Nature-based Climate Solutions in Singapore.

But first and foremost, businesses need to know where to source for quality carbon credits.

Last month, a group of financial firms announced the launch of a new Singapore-based global carbon exchange and marketplace for high-quality carbon credits. Expected to be operational by the end of 2021, the joint-venture is tasked to overcome the lack of transparency and ineffectiveness of some carbon projects that currently undermine the market.

It will also leverage satellite monitoring, machine learning and blockchain to enhance the transparency, integrity and quality of carbon credits. By the end of the decade, the market could a huge multi-billion dollars opportunity, said Piyush Gupta, chief executive officer of DBS Bank, at a press conference.

But nature-based solutions should be part of a portfolio of different solutions that include the decarbonisation of a company’s footprint, cautioned Shyla Raghav, vice president of climate change at non-governmental organisation Conservation International at a webinar.

“Offsets shouldn’t be a replacement for decarbonisation. We’re at a point of urgency with climate change that it’s not a question of either/or. It should be both, in parallel and rapidly accelerated,” said Raghav.

Best opportunities in Southeast Asia

The NUS Centre for Nature-based Climate Solutions estimates that the preservation of tropical forests alone can generate US$46 billion worth of carbon credits annually, which would both pay for their own conservation and reap returns for investors.

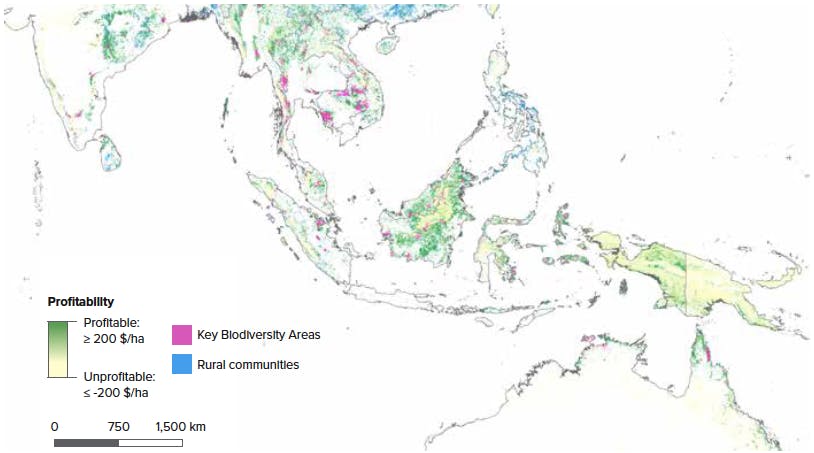

With carbon-rich ecosystems like peatlands and mangroves, Southeast Asia has the highest global concentration for carbon prospecting for investments in nature-based solutions. The top five countries in the region in terms of return-on-investment from nature-based carbon projects are Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia and Myanmar.

Southeast Asia carbon prospecting profitability and co-benefits. The region holds the highest potential for not only nature-based solutions return-on-investment, but also added key biodiversity co-benefits particularly in Malaysia, Thailand and Cambodia. Image: Koh et al.

“From my perspective as a conservation scientist, the protection of our remaining natural ecosystems from the threats of deforestation are the highest priority nature-based solutions to invest in,” Koh told Eco-Business.

“These include certified and credible deforestation and forest degradation projects (REDD+) that deliver not only climate mitigations benefits by avoiding the loss of their natural carbon stocks, but also co-benefits such as conserving biodiversity and safeguarding rural livelihoods,” he added.

On top of the financial returns of nature-based solutions, another plus point is the co-benefits they provide. Nature-based solutions bring a myriad of social and environmental co-benefits such as storm protection, water filtration and local employment gains.

A feasibility study on the market potential and drivers of nature-based businesses in Southeast Asia identified six business models that are likely to have long-lasting impact in the region. Under the category of ‘terrestrial’, the business models include forest carbon and agroforestry commodities with carbon and soil carbon, while the category of ‘marine’ included integrated marine protection areas with blue carbon, mangroves and seaweed production.

“These business models make sense from the perspectives of climate change mitigation and nature conservation, provided that they are implemented with proper safeguards. For example, the project implementers must be able to prove the value-add and non-trivial values of these nature-based solutions for avoiding emissions, conserving biodiversity and safeguarding rural livelihoods,” said Koh.

Next steps: Increasing collaboration in the region

But there are also limitations to the scaling up of forest conservation sites.

According to researchers of the carbon prospecting study, unless the price of carbon increases significantly, many forest preservation projects would not be viable as the cost to manage the land would be more than the potential returns.

Even for projects that are profitable, there are competing land uses that pose barriers to forest conservation, such as the use of land for agriculture in Indonesia.

In addition, the main issues with nature-based carbon projects and products have to do with their uneven quality, supply liquidity, and lack of pricing transparency, said Koh.

“Addressing these issues requires a multi-sectoral approach across Southeast Asia. For example, governments in the region may need to coordinate among themselves to create the regulatory environment to raise the floor on the credibility and integrity of nature-based carbon projects,” he said.

The research sector could help by developing better technologies, methodologies and standards for measuring, monitoring, reporting and verification of these projects, Koh added.

The private sector can also support the global transition to a low-carbon economy by stimulating investment, advocating for policy development, creating financial partnerships to de-risk nature-based projects, or advancing technologies to support project implementation and monitoring.

“Lastly, the corporate and government sector could create national or regional carbon exchanges to facilitate the trade of nature-based carbon as a new type of commodity, as well as ensure carbon price transparency, stability of demand and liquidity of supply,” Koh said.