Indonesia goes to the polls to choose a new president on 14 February.

Unlike the previous election in 2019, all three presidential and vice-presidential candidates pairings – Anies Baswedan and Muhaimin Iskandar, Prabowo Subianto and Gibran Rakabuming Raka, and Ganjar Pranowo and Mohammad Mahfud – have promised to take climate action if they win.

These pledges are crucial for a country that ranks in the top third of the most at-risk nations to climate change, and is one of the world’s biggest carbon emitters, with much of its climate pollution coming from forest and peatland clearance as well as burning coal for energy.

Indonesia has a mixed track record in responding to the climate crisis over the past decade, since incumbent president Joko Widodo, better known as Jokowi, came to power. Though Indonesia has received international acclaim for slowing the rate of deforestation during Jokowi’s administration, 3.1 million hectares of rainforest were lost between 2015 and 2022.

The expansion of mines and plantations, as well as the development of national infrastructure projects have caused an estimated 2,393 agrarian conflicts – a 100 per cent-increase compared to the previous decade, according to data from Agrarian Reform Consortium, a non-profit.

Production of the most climate-harming fossil fuel is increasing rapidly. Coal production reached 686 million tonnes in November 2023 and is projected to rise of 710 million tonnes this year. Coal production in the world’s biggest exporter of the most polluting fossil fuel is not expected to peak until 2030.

Indonesia’s booming industry for nickel has drawn criticism for ignoring the socio-economic and ecological impacts of mining the important transition metal. In the extraction heartlands of Sulawesi and the Maluku islands, fishermen have blamed nickel mining and smelting on the depletion of fish in their traditional fishing grounds.

Jokowi’s legacy has left a wide range of environmental and social issues for the incoming president to address. But while all three presidential candidates have included climate in their vision statements, other issues such as the economy and infrastructure development have dominated their campaigns, commented Abdul Ghofar, urban and pollution campaign manager at WALHI, Indonesia’s largest environmental advocacy group.

Candidates’ climate policies only partially address the issue, and do not fully address the root causes of the climate crisis and its far-reaching effects, Ghofar noted.

A study published in December by energy transition non-profit Indonesia Cerah concluded that climate issues and the energy transition are not top priorities for Indonesia’s election hopefuls.

The study’s findings played out in a vice-presidential debate held on 21 January in which the candidates gave unconvincing responses to questions from panellists and used the debate to score political points against their opponents.

Eco-Business has analysed the policies of the three candidates to understand who has the most climate credibility.

Anies Baswedan, the former governor of Jakarta, on the campaign trail. Image: Media Indonesia on X

Anies Baswedan – Muhaimin Iskandar: Social and ecological justice but light on detail

Under the banner “A just and prosperous Indonesia”, Anies Baswedan, the former governor of Jakarta, and his running mate, Muhaimin “Cak Imin” Iskandar, have been campaigning with a focus on ecological justice.

The platform consists of eight elements, including strengthening environmental governance, renewable energy and the green economy, climate adaptation, air, water and waste pollution, and natural disaster resilience. On social and economic injustice, there are three key issues: unequal access to education, poverty, unemployment, and income inequality, and the climate crisis.

Unlike the other two candidates who have focused more on the economy, Anies-Imin have made social and ecological justice a foundation pledge, with a focus on intergenerational justice for communities affected by development, including Indigenous peoples and other marginalised groups.

Anies-Imin also highlighted food security as a key issue by ensuring affordable fertiliser and other agricultural resources, as well as promising to retire coal-fired power plants early in Java and Bali, followed by other islands, to help meet Indonesia’s national decarbonisation goal of net-zero emission by 2060.

At the latest vice-presidential debate, Muhaimin’s opening statement highlighted the importance of intergenerational climate, ecological, and agrarian justice. However, when challenged on deforestation, Muhaimin only talked about reforestation as a solution and overlooked the systemic issues that drive deforestation.

He did not elaborate much on his vision for food industrialisation, and whether he was referring to contract farming or reforming land ownership rules – a persistent issue in Indonesia.

“[Anies-Imin] successfully addressed and criticised the failures of the incumbent government, but they failed to elaborate on their own ideas,” said Ghofar.

Anies’ track record as Jakarta governor from 2017-2022 has raised questions about his climate and environmental policies.

Prior to his election as governor in 2017, Anies had opposed a major land reclamation project that would affect 17 islands around North Jakarta. But after he came to power, several islands were given a permit to continue construction. While Anies did stop some reclamation projects, he was heavily criticised by environmental activists and fishermen for greenlighting the ones he did.

Anies has also been challenged legally over his environmental policies while Jakarta governor. In 2019, Gerakan Ibu Kota, a Jakarta residents group, filed a lawsuit over worsening air quality in the capital, suing Anies as well as Jokowi and the governors of Banten and West Java.

“While other top officials decided to appeal, Anies did not and instead abided the court’s decision that found him guilty of negligence over air quality in Jakarta,” commented Dwi Sawung, infrastructure and spatial plan campaign manager at WALHI.

By creating the Jakarta Cleaner Air 2030 roadmap, at least he left a “good legacy” for tackling air pollution, Sawung said, although critics have challenged the roadmap for not going far enough to cut pollution in what regularly ranks as the world’s most smoggiest city.

Prabowo Subianto addresses young supporters at an event in Jakarta. “Indonesia’s future belongs to young people,” he said. Image: Prabowo on X

Prabowo Subianto – Gibran Rakabuming Raka: Food self sufficiency but more deforestation?

Defence minister Prabowo Subianto with Jokowi’s son, Gibran Rakabuming Raka, as his running mate, have set out to transform Indonesia into a renewable energy and bioenergy powerhouse, using natural resources to achieve energy independence.

In their mission statement, Prabowo-Gibran identified a number of strategic challenges for Indonesia over the next five years, including the impacts of climate change, such as lowering food production and rising food prices.

Among their top priorities is for Indonesia to achieve self sufficiency in food, energy and water. A key initiative for doing so is the food estate programme, which aims to develop vast fields of rice, corn, cassava, soy and sugarcane. In tandem is a programme for agrarian reform to improve the lives of farmers and boost food production.

On energy, the duo plans to develop biodiesel and bioavtur from palm oil, as well as bio-ethanol from sugarcane and cassava. Through this strategy, they are aiming to produce diesel with 50 per cent palm oil (known as B50) and petrol with 10 per cent bioethanol (known as E10) by 2029. Prabowo has claimed that B50 biodiesel will not contribute to air pollution.

However, these plans could lead to more deforestation, suggested Sawung. Boosting biodiesel production could mean developing more palm oil plantations, while the food estate programme that has already been running under Prabowo’s leadership as defence minister has been heavily criticised. The programme mirrors that of the Mega Rice Project from the mid-1990s, which failed to boost agricultural yields and left vast tracts of carbon-rich peatlands drained.

“There are around 2.7 million hectares of land that have been converted for the food estate programme. It is clear that the programme has failed to meet its goals and has caused socio-economic and ecological problems. They should be brave enough to discontinue the project or thoroughly evaluate it and change their approach,” added Sawung.

During the vice-presidential debate, Gibran pledged to continue the incumbent government’s commitment to industrial downstreaming, but did not address emerging problems in the nickel sector. An explosion at a nickel smelter in Morowali, Central Sulawesi in December that killed 21 people highlighted emerging problems in the downstreaming policy started by President Jokowi that Prabowo-Gibran has pledged to continue.

Questions have been raised about how Prabowo’s business interests might affect his policies, since the defence minister owns 500 thousand hectares of land in Sumatra and Kalimantan. The food estate programme is suspected to be linked to a private entity run by Prabowo allies, as well as by several people from his political party, Gerindra.

“[Prabowo-Gibran] tend to see environmental issues through a business lens, instead of providing real solutions to the climate crisis. Although they use jargon like “no one left behind” and claim to be finding the middle ground between profit and sustainability, their approach is still based on commodification of resources for profit,” said Ghofar.

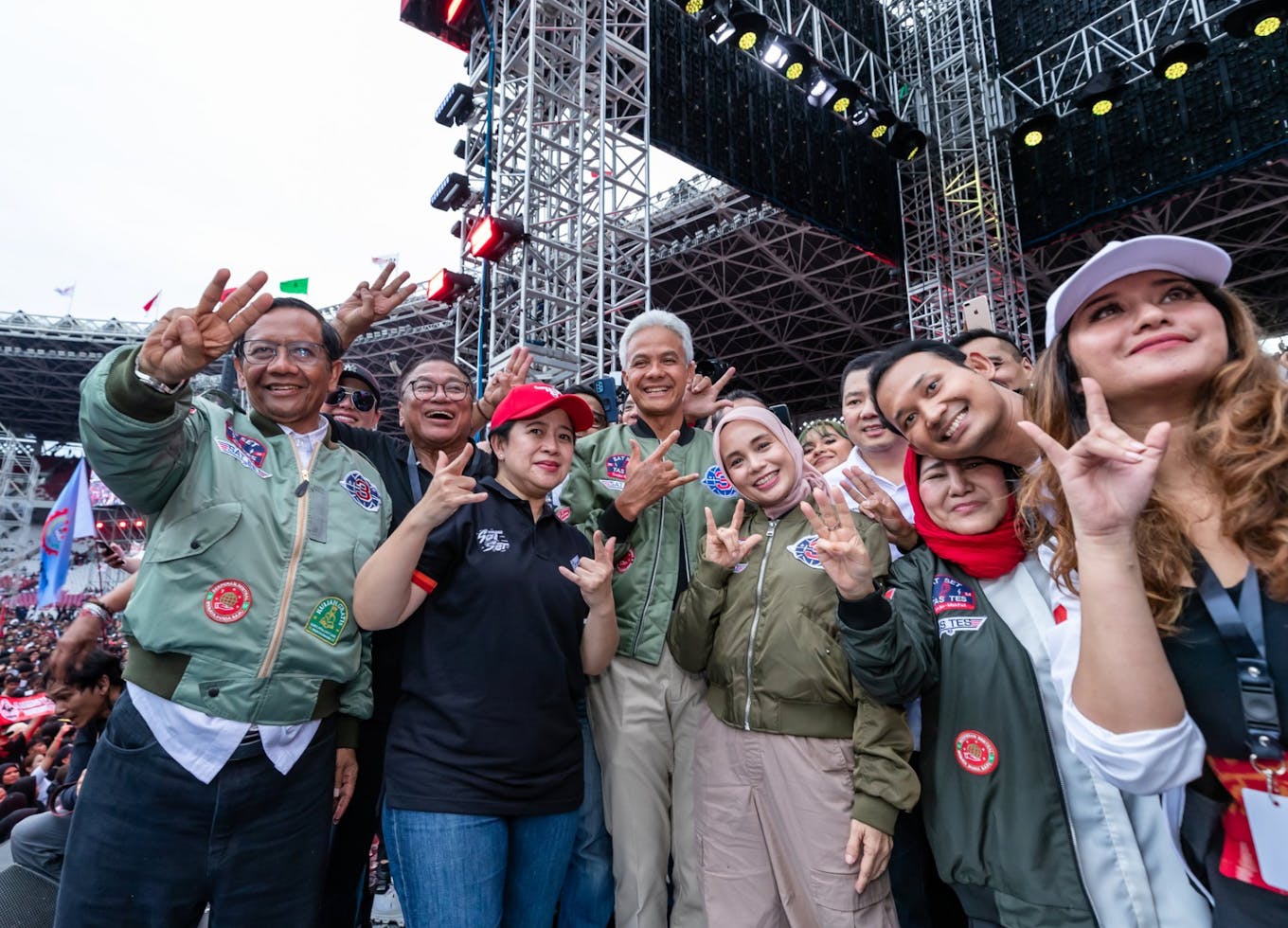

Mohammad Mahfud (far left) and Ganjar Pranowo (centre) on the campaign trail in Jakarta. Image: Ganjar/Pranowo on X

Ganjar Pranowo – Mohammad Mahfud: Green and blue economy push but with governance concerns

The third election hopefuls, led by the former governor of Central Java, Ganjar Pranowo, are basing their campaign around the green and blue economy.

Their green economy plan includes cutting greenhouse gas emissions by accelerating the adoption of clean energy, with a target renewables ratio of 25-30 per cent of the energy mix by 2029, up from 10 per cent currently. This is a slightly more ambitious target than the previous 23 per cent by 2025, which the incumbent government recently lowered to between 17 and 19 per cent by 2025.

They also intend to decentralise Indonesia’s energy system, with a plan for villages to become self sufficient in energy by sourcing renewables locally, and boost the circular economy with an integrated waste management system that enables people to trade their waste for cash (schemes like this already exist in Indonesia, albeit on a small scale).

Ganjar-Mahfud plan to rejuvenate the blue economy, introducing a quota-based fishing policy and new rules for zoning Indonesia’s waters to preserve marine biodiversity. They also say they’ll get tough on water polluters and work to improve protections for maritime sector workers and fishers.

In the vice-presidential debate, Mahfud covered sensitive issues that are rarely touched on in Indonesian politics, including the criminalisation of environmental activists, illegal mining and the mafia tanah, or land mafia, which collect rent from the transfer of ownership and control over land.

According to WALHI, 827 environmental defenders have faced criminal charges during the Jokowi administration. Although regulation to protect activists is enshrined in the constitution – Law No. 32/2009 on Environmental Protection and Management Article 66 – the regulation is not considered effective and is therefore a threat to activists’ rights.

While Mahfud raised the issue during the debate, he did not offer concrete solutions to protect activists nor a way to give the regulation teeth, commented Ghofar.

Mahfud was similarly vague about how to tackle illegal mining, Ghofar said. He did not provide solutions, such as pursuing law reform and setting strict regulations, which he had the power to do as he was previously coordinating minister for political, legal, and security affairs.

Ganjar’s track record as governor of Central Java raises questions about how he would approach environmental and social governance. In 2022, security forces cracked down on villagers – 67 people, including 13 children, were arrested – protesting against the impacts of a planned quarry in Wadas, Central Java, that would supply materials to build a new dam.

The Bener dam project is a national initiative instigated by Jokowi, not Ganjar himself. However, activists objected to the use of intimidation tactics by the local police. “Ganjar should have been able to intervene in this case,” commented Sawung. “Although it was a national project, he could have initiated a dialogue with the villagers, or delay the project.”

In another case of conflict with local communities over development, Ganjar decided in favour of a controversial cement factory in Rembang regency that had been opposed by local farmers who were concerned about groundwater depletion and pollution. Ganjar issued a permit for the factory in 2017 despite an Indonesian Supreme Court ruling the previous year to halt construction of the factory.

The vote for practical climate solutions

Climate issues are closely intertwined with other sectors in Indonesia, as seen by the rising price of staple foods exacerbated by the climate crisis. The country needs a leader who can provide workable, detailed solutions that join the dots between climate and key sectors such as energy, waste, transport, and infrastructure.

While all three candidates have climate and environmental programmes, it is important that they avoid false solutions and lay solid foundations for navigating the climate crisis as they chart a course for Indonesia to become a developed country by 2045.

Critical to this aim is the understanding of the climate crisis as a systemic issue that affects all aspects of life, from local communities to big business. That requires a range of practical and technical solutions and a holistic approach to managing climate risk that includes all elements of society, said Ghofar.

The election could be a catalyst for change in how Indonesia responds and adapts to climate change. But the door should be kept open for democracy to enable Indonesians to push the government to make better choices as climate impacts intensify, he said.

For more Indonesia ESG and sustainability news and views, subscribe to the Eco-Business Indonesia newsletter here.