Since the adoption of the landmark Paris Agreement on climate change in 2015, global momentum to tackle the climate crisis has been building.

Progress has been made on almost every front, from bold corporate emissions-reduction targets and investors shifting away from coal to a surge of support for net-zero targets and a rising movement of youth activists from Uganda to India, culminating in Greta Thunberg being recognised as Time Magazine’s 2019 “Person of the Year.”

At the same time, the progress on climate action has not been anywhere near fast enough.

“

Business executives, city mayors, investment bankers, technological innovators and young people everywhere have spoken: They want greater global action on climate change. Now countries need to step up.

The climate movement faced plenty of troubling headwinds over this period. President Donald Trump officially withdrew the United States from the Paris Climate Agreement in November 2020 — the only country to do so — although President-elect Joe Biden has promised to rejoin on his first day in office in January 2021.

While the coronavirus pandemic led to a historic drop in global emissions this year, this drop will be a blip in the ongoing trend of ever-climbing GHG emissions unless backed up by changes in policy and business practices. Last year was the second-hottest on record globally, and 2020 is on track to be the warmest year ever.

From wildfires in Australia and the western United States to this year’s record-breaking hurricane season, communities around the world continue to face devastating extreme weather events, many exacerbated by the climate crisis. A lot of work lies ahead of us.

The coronavirus pandemic, while first and foremost a health, employment and economic crisis, will also impact efforts to advance climate action.

On the one hand, most leaders are not focused on climate action these days, and the COP26 climate summit originally scheduled for November 2020 in Glasgow was postponed until next year. On the other hand, this health crisis shows that countries can respond rapidly to a global emergency.

Here are six ways the world has shown it’s ready for more ambitious climate action since the Paris Agreement was adopted in 2015:

1. Over 1,000 big companies pledged major emissions reductions

Private sector leaders increasingly recognise that transitioning our high-carbon economy to one built on low-carbon activities is not only essential to limit dangerous climate change impacts; it’s also good for companies’ bottom lines.

Under the Science Based Targets initiative, over 1,000 companies have committed to set emissions reduction targets based on the science, and more than 340 have committed to set net-zero targets across their operations and value chains. The net-zero targets align with limiting warming to 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F).

Collectively, these high-ambition companies — including many globally recognised brands, from Chanel to Nestlé — represent $3.6 trillion and have an annual carbon footprint larger than the annual emissions of France.

Companies’ approaches to cutting their emissions vary. For example, 270 are committed to transitioning to 100 per cent renewable energy. This includes Nike, which already powers all its North American facilities through renewables.

The Consumer Goods Forum recently launched an initiative leading major brands, retailers and manufacturers in an effort to eliminate deforestation and forest degradation from supply chains of commodities including soy, palm oil and paper.

Ninety-two companies — including Air New Zealand, Baidu and HP — have joined EV100, a worldwide initiative seeking to accelerate the transition to electric vehicles by 2030. And IKEA and H&M — companies known globally for the affordability of their products — are exploring ways they could profit from repairing and reselling products in a circular economy.

Many of these companies are leaders within their sectors and are setting a new standard for what corporate climate action should look like. Microsoft, one of the world’s largest companies, will shrink its carbon footprint and invest in carbon removal solutions to become carbon negative by 2030.

2. Major cities are improving urban life while building climate resilience

More than half the world’s population lives in cities, and the U.N. predicts that percentage to grow to two-thirds of humanity by 2050. As a result, how cities act now against climate change will directly affect the lives of billions.

Worldwide, around 400 cities have committed to reaching net-zero emissions by 2050, and more than 10,500 have joined the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy.

In the United States, cities are a major player in America’s Pledge, a coalition of cities, states and businesses committed to fulfilling the Paris Climate Agreement’s target despite the Trump administration’s withdrawal. Together, these entities account for almost 70 per cent of the US economy. If they were a country, their economy would be larger than China’s and second only to the full United States.

Many individual cities worldwide are also taking commendable action to reduce emissions and create better lives for their residents. In Medellín, Colombia, the installation of an aerial tram system called Metrocableis linking low-income hillside communities with the center of the city and thus boosting access by residents to jobs, education and other services.

The mayor of Paris made her plan for a “15-minute city,” where residents can meet all their needs within 15 minutes of traveling from home, a cornerstone of her re-election campaign. And in China, the city of Shenzhen more than tripled its number of electric buses since 2015, making it the first city in the world to electrify 100 per cent of its bus fleet.

Others are focused on adapting to a changing climate. In the northern Indian city of Gorakhpur, city officials are encouraging a range of tactics — from reducing monoculture to protecting water bodies — to reduce flooding and boost resilience as monsoons get stronger and more unpredictable.

To help all cities reduce emissions and weather climate impacts, WRI and C40 have created a roadmap for equitable city climate action that will include and benefit all residents without leading to unintended burdens on poor and otherwise vulnerable communities.

3. Financial institutions recognise that funding fossil fuels is a bad investment

To shift onto a more sustainable path, the world’s leading public and private financial institutions need to not only invest more in the new clean alternatives, but also stop investing in the old polluting technologies.

In the wake of the Covid-19 crisis, governments are providing unprecedented levels of investment to reflate economies and generate jobs. As they do so, there is strong evidence that these investments should be targeted to projects that are low carbon and climate resilient.

South Korea provides a good example; after the 2008-09 economic crisis, the country invested more in green stimulus measures than any other OECD country — and was one of the countries that rebounded the quickest.

As a recent WRI paper revealed, the countries that invested in green measures after the Great Recession can show what worked, what didn’t and how to apply these lessons to green Covid-19 recovery.

So far, the European Union is leading the pack when it comes to investing in green recovery. About 30 per cent of its €750 billion ($891 billion) EU-wide stimulus plan and its €1.1 trillion ($1.3 trillion) 2021-2027 budget will be dedicated to climate-friendly investments.

The European Investment Bank (EIB) aims to align its strategy with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5 degrees C goal by the end of 2020 and plans to stop funding oil, gas and coal projects at the end of 2021 — both pioneering moves for multilateral development banks. In addition, the bank’s new “climate roadmap” promises to invest €1 trillion ($1.2 trillion) in climate and other green actions by 2030.

Meanwhile, more than 130 private banks — representing one-third of the global banking sector — signed onto the Principles for Responsible Banking. This framework that seeks to align banking practices with the Paris Agreement.

Through the United Nations-convened Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance, 33 major institutional investors with $5.1 trillion in assets committed to net-zero investment portfolios by 2050.

In January 2020, BlackRock, the world’s largest asset management firm which alone manages $7 trillion, announced that it was shifting its financial strategy to center around climate change.

With this move, it joined more than 370 other investors in an initiative called Climate Action 100+, whose members are engaging companies that produce two-thirds of global industrial emissions.

4. Technological advances make renewable energy and other solutions more attainable

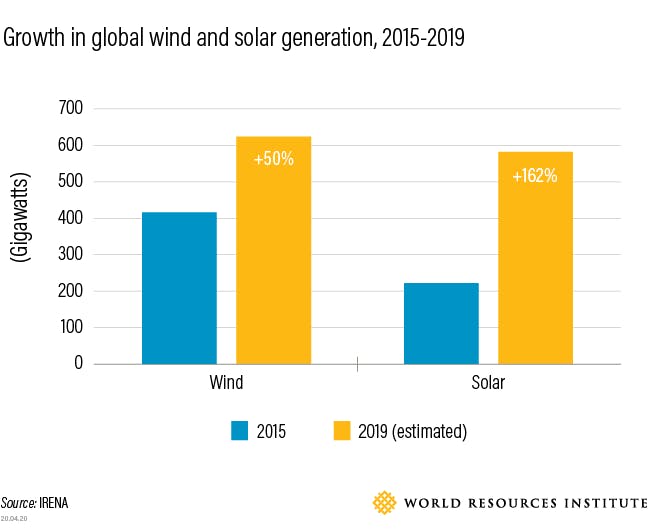

Growth in global wind and solar energy, 2015-2019. Image: IRENA

Renewable energy is increasingly cost-competitive with coal. Between 2010 and 2019, solar energy prices dropped 90 per cent. In sunny regions around the world, it’s already cheaper to get electricity from solar than fossil fuels.

Similarly, the cost of wind energy has declined significantly in recent years and is cheaper than natural gas in some regions, including parts of the United States.

As prices drop and the adoption of renewable energy expands, so does the industry behind it. In the United States, clean energy already employs almost 3.3 million Americans, more than fossil fuel generation.

The last few years have also seen further signs of technological progress toward tipping points for a zero-carbon future. Electric vehicle technology improved so quickly that an increasing number of major automakers, including Toyota and Daimler, are planning to stop making internal combustion engines.

Iron and steelmakers, which have struggled to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, are now exploring using hydrogen as a clean fuel to replace carbon within their industrial processes.

Knowledge about the opportunities to sequester carbon in trees and soil, as well as how to sequester carbon industrially, is also advancing rapidly.

5. Expanding social movements reflect the public’s growing demand for climate action

In 2019, Greta Thunberg and other young climate activists exploded onto the global stage with their weekly school strikes, known as Fridays for Future, protesting the lack of climate action by world leaders.

Bolstered by other youth-fueled activist groups — including the Sunrise Movement and Extinction Rebellion — more than 7 million people across 185 countries joined the world’s largest climate strike in history in September 2019 to demand stronger governmental action.

And during the 2020 protests for racial justice in the United States and around the world, participants frequently spoke out about the disproportionate threats that climate change and other environmental hazards pose for communities of color and other vulnerable groups.

But activists aren’t the only ones who want climate action. According to a September 2019 poll taken in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Brazil, France and Poland, climate change ranks ahead of migration and terrorism as the most important issue facing the world.

In a separate US poll conducted in April 2020, two in three Americans are at least “somewhat worried” about global warming; the majority of both Republicans and Democrats support the United States’ participation in the Paris Climate Agreement.

6. Country-level action is starting to accelerate

Business executives, city mayors, investment bankers, technological innovators and young people everywhere have spoken: They want greater global action on climate change. Now countries need to step up.

Twenty-five countries and the EU are currently working toward some sort of net-zero commitment (in many cases by 2050, though some countries such as Denmark and Finland have earlier deadlines).

This year several Asian economic powers made net-zero commitments, including South Korea and Japan (by 2050) and China — the world’s largest emitter — by 2060.

However, all these goals are purely aspirational if they are not reflected in ambitious actions that countries begin to take now, Including their economic recovery plans from Covid-19 and the 2030 national climate plans countries are slated to update under the Paris Agreement this year.

So far, 15 have already done so, and 130 others have promised to follow suit. Ensuring that they follow through by COP26 will be critical to get global climate action on track.

Achieving a net-zero future

Slashing greenhouse gas emissions can’t be done overnight; countries should use their short-term climate plans as steppingstones that can help them reach a net-zero future.

As countries around the world now start to consider how to approach their economic recovery following the coronavirus crisis, they can use this turning point to accelerate investments in a low-carbon, inclusive and resilient economy to build back a better future for all.

Molly Bergen is communications manager for WRI’s Climate Programme. Helen Mountford is the vice president for Climate and Economics at WRI. This post is republished from the WRI blog.