What makes bonds “green” is not yet well established.

A green bond is a debt security that exclusively funds projects with environmental or climate-related benefits. As a financial instrument that aims to mitigate the negative impacts of human economic activity on climate change, green bonds have been gaining more attention from financial market participants.

Since the first green bond, Climate Awareness Bond, was issued in 2007, the global green bond market has expanded rapidly. According to the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI), annual global green bond issuance reached $155.5 billion in 2017.

Despite its rapid growth, the green bond market remains much smaller than conventional bond markets, accounting for less than 2 per cent of global bond issuances in 2016. One salient barrier to further develop the green bond market is the lack of a universally accepted definition of green bonds and commonly recognised standards and regulations.

In the conventional bond market, credit ratings, some of which are globally recognised, are widely used to capture default risk. These ratings provide financial risk assessment about a bond issuer or an investment project.

However, in the green bond market, such a commonly accepted standard of greenness—what makes bonds “green”—is not yet well established. The lack of a widely accepted standard not only exposes investors to information asymmetry, but also interferes with a clear pricing mechanism.

While in the conventional bond market, higher (lower) credit risk is compensated with a credit premium (discount), in the green bond market it is still unclear whether a premium/discount on greenness reflects the bond’s environmental merit or just demand-supply imbalance for green bonds.

How do we measure the “greenness” of a green bond?

The International Capital Market Association introduced in 2014 the Green Bond Principles (GBPs) to help define “greenness.” More specifically, it prepared a guidance based on four key elements of a green bond issuance—use of proceeds, process for project evaluation and selection, management of proceeds, and reporting—and in 2015 recommended a voluntary external review.

Separately, the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) also maintains a Climate Bonds Standard (CBS) and an international certification scheme for green bonds. The CBI scheme includes a framework for monitoring, reporting, and ensuring conformance with the CBS.

The CBS has pre-issuance and post-issuance requirements that need to be met by issuers seeking certification. In both stages, issuers are required to obtain independently approved Climate Bond Verifiers to assess whether a bond complies with the requirements of the CBS.

“

Other things equal, investors will tolerate a relatively lower yield for projects that have externally certified environmental benefits.

The CBI framework is fully aligned with the GBPs and certified by an independent CBS Board. Other regional or country green bond standards are also being developed.

The June 2018 edition of the Asia Bond Monitor (ABM) presents some evidence on the pricing mechanism in the green bond market. The study empirically examines whether green bonds that have an external review are compensated with a green discount compared to other green bonds that do not.

To obtain the premium (or discount) of a green bond, the ABM compares yields on a green bond and a matching conventional bond. A matching conventional bond is issued by the same issuers and has the same bond characteristics—credit rating, maturity, denominating currency, coupon type, option clause—as the green bond.

Green bond market does not systematically price in “greenness”

These matching method controls for characteristics that are the conventional bond market already prices in. Hence, the yield spread between a green bond and its matching conventional bond presents a broad measure of the yield premium in the green bond market.

Furthermore, since the green bond market is less liquid than the conventional bond market, the analysis adjusts for liquidity to get a more accurate measure of the yield spread or premium.

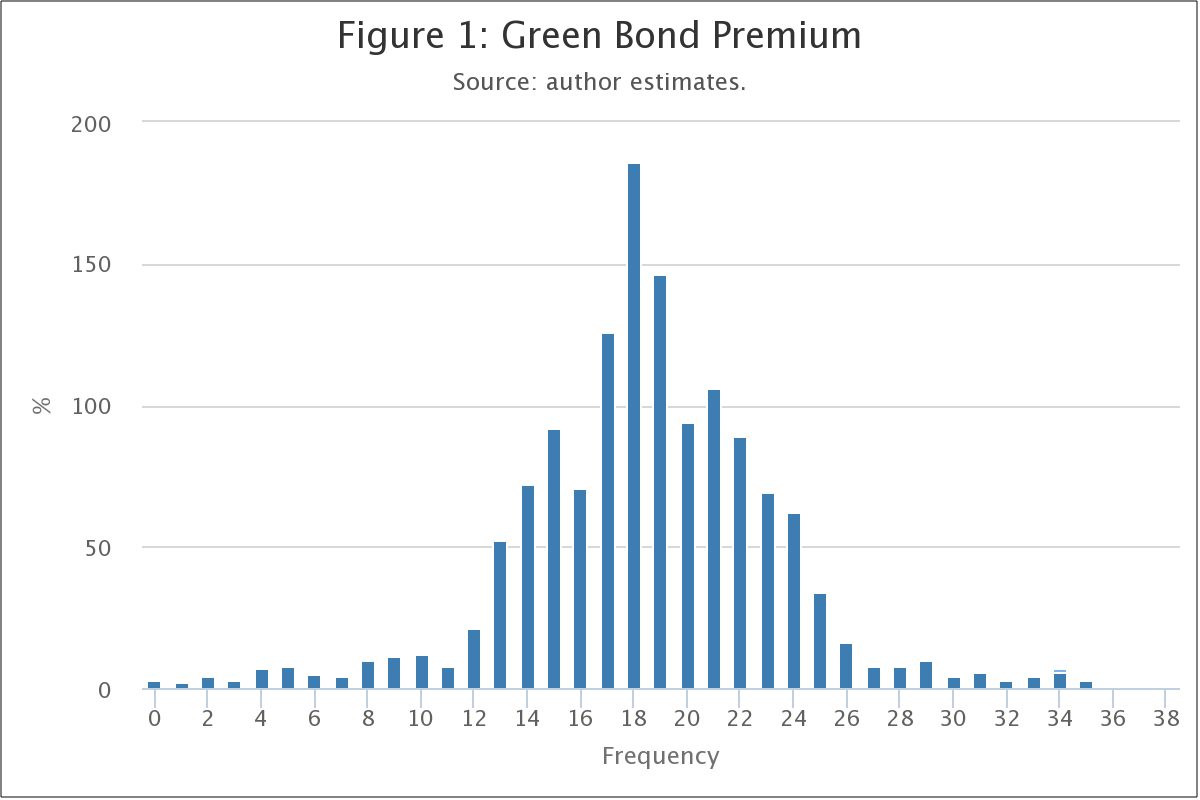

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the green premium in the sample. On average, the green premium is close to zero, indicating that the green bond market does not systematically price in greenness.

Figure 1

However, a close-to-zero average green premium does not necessarily mean that green bonds are not compensated for their environmental benefits. Further research using panel data will provide more information on what kinds of green bonds tend to enjoy a lower yield compared to others.

The empirical results show that after controlling for common pricing drivers such as maturity, issue size, credit rating, denominating currency, project sector and initial yield level, green bonds that obtain an independent review or CBI certification enjoy a 7 bps or 9 bps discount comparing to those that do not. This confirms the importance of a widely recognised and accepted standard in the green bond market.

Fluid green bond markets to spur more green investments

Such a standard enhances information quality and lowers the issuer’s financing costs. Measures that proxy for greenness, such as an external reviewer, or some well received green bond certification, can thus boost investor confidence.

Other things equal, investors will tolerate a relatively lower yield for projects that have externally certified environmental benefits.

Another interesting finding is that euro-denominated green bonds tend to have a lower green bond premium compared to green bonds denominated in other currencies. This may be largely due to the high degree of interest in environmental sustainability within the EU.

Green bonds ultimately finance investments that help tackle climate change and promote a cleaner environment. As such, vibrant, well-functioning green bond markets can become a vital source of funding for green investments.

While green bond markets have grown rapidly in recent years, there is a lot of scope for further expansion. The ABM analysis suggests that it is imperative for policymakers to develop widely accepted definitions and standards of greenness for green bonds.

Doing so will contribute to more accurate pricing of green bonds which, in turn, will encourage greater participation of both issuers and investors, and thereby foster further development of bond markets.

Dr. Hyun is a visiting scholar at the University of Southern California’s Department of Economics, Donghyun Park is the Principal Economist at the Economic Research and Regional Cooperation Department at ADB, and Shu Tian is an Economist with ADB. This post is republished from the ADB blog.