Reading this blog entry, you are most likely already aware of the fires in Riau province in Sumatra that have caused haze problems as far away as Singapore and Kuala Lumpur. You are no doubt aware that these fires indicate high rates of deforestation and high emissions of CO2 from peatlands. But you probably also share my concern about the lack of information and want to know more.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Last week (28-30 August), a team from CIFOR travelled to Riau on a fact-finding mission to better understand the issues from a local and in-depth perspective. We also wanted to identify priority research topics related to governance, livelihoods, the environment and economics of the Riau landscape.

We decided that the Giam Siak Kecil-Bukit Batu biosphere reserve would be a suitable landscape to examine more closely. The area was acknowledged as a biosphere reserve by UNESCO in 2009 and extends over 700,000 ha – almost 10 per cent of Riau province – in an area dominated by peatlands.

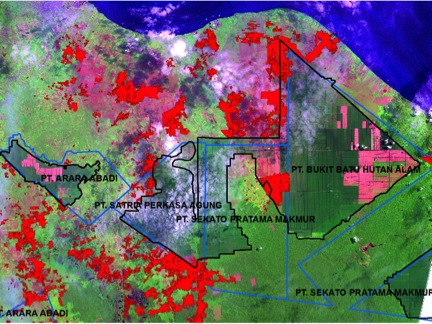

Further, it includes the full range of land uses we are interested in: reserves of pristine forests; corporate-scale planted forests; large expanses of oil palm plantations; and land managed by local communities and stakeholders. Figure 1 also illustrates that many of the 2013 fires occurred within this reserve.

“

One of our preliminary conclusions is that one cannot assume that land within a concession boundary is fully controlled by the corporation in question. Within these large areas, up to a quarter is said to be managed by local stakeholders.

This landscape has been subject to massive land-use change, as described in this assessment from 2003. Only a fraction of the once-dominant natural forest remains. The conversions we see today are not a new phenomenon – the development of commercial agriculture and forestry has been part of policy and practice for decades, which is an important perspective to have.

So what can we say about recent events in this landscape?

Before our field visit, CIFOR analyzed the fire events in some detail using remote sensing and map data. Using higher-resolution imagery with the hotspot indications, we were able to confirm fire scars in the landscape. Our preliminary conclusion was that the fires were mainly located in areas showing patterns of plantation management. We also concluded that most fires occurred outside the corporate-scale concessions, with about a quarter inside. We identified 140,000 ha of burned area within the studied 3.5 million ha, corresponding to 40 per cent of Riau province, with a high proportion of the Giam Siak Kecil-Bukit Batu biosphere reserve (three per cent) showing scars from fire.

Figure 1: Remote sensing analyses of the Giam Siak Kecil-Bukit Batu biosphere reserve, indicating June 2013 fires in bright red, located inside forest reserves, planted forests and in transition zones. See here for more detail.

Remote sensing will obviously not inform us about the underlying reasons and purposes for the fires, nor provide information on livelihoods, governance, conflicts or in-depth environmental impact. Our field visit, however, helped us to better understand these matters and identify topics for further research.

Flying over the Riau landscape (Figure 2), we were able to conclude that the remote sensing indications of fires were accurate. We also observed that the fires appeared to be due to agricultural practices exclusively, mainly conversion of forests into oil palm plantations. We saw a few cases where existing plantations and planted forests had been damaged by fires, but these appeared to be exceptions, and possibly not intentional. We observed fires within concessions and inside forest reserves, as well as outside federally designated lands.

Information from local stakeholders and professionals confirmed these general patterns.

One of our preliminary conclusions is that one cannot assume that land within a concession boundary is fully controlled by the corporation in question. Within these large areas, up to a quarter is said to be managed by local stakeholders. There are tensions between the large-scale top-down allocation and plantation management of these lands on one hand, and claims to the same lands through local agricultural practices and customs on the other. The legal situation is therefore not entirely clear, and fires or land conversions inside concessions may be linked to these governance issues. One should therefore be cautious in drawing the conclusion that corporations are causing fires on their lands, based only on remote sensing overlaid on general concession maps. That said, one should also avoid making conclusions as to the responsibilities for those fires given that there is clear legislation defining the obligations of concessionaires.

Figure 2: Fire in forests (top images), fire scar extending into planted forest (bottom left), newly established oil palms (bottom right). Giam Siak Kecil-Bukit Batu biosphere reserve, 29 August 2013.

Another observation is that investments in oil palm planting is profitable enough to attract capital in large quantities, leading to the substantial land conversions we observe. In fact, we neither observed nor heard of any reason for land conversion other than palm oil production. The main sources of capital and the pattern of investments appear to have shifted to entrepreneurs that are neither large corporations nor local ‘smallholders’, as has also been observed by the World Agroforestry Centre. Clearly, we don’t have the full picture of these investment trends – who is behind them, to what extent the investments are legitimate, how they impact local stakeholders and the environment, or how the value chains of oil palm are operating in relation to laws on issues like land use and corruption.

Where to go from here? CIFOR is engaging with partners to do further in-depth research of the Riau landscape, including governance and livelihood issues. One challenge we have is that the attention span for land management issues is very short at the policy level. We hope our contribution will both enrich the broader understanding and help maintain interest in a policy dialogue that integrates issues across the landscape and across sectors.

This is precisely in line with the ambitions of the Global Landscapes Forum, in which the Riau example of forestry and agriculture interlinkages is particularly relevant. This debate will certainly be a main feature in Warsaw 16-17 November.

Peter Holmgren is the director general of the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). This post originally appeared here.