Southeast Asia is at high risk from the adverse impacts of climate change. Average yields of cereal production in the region including that of rice, wheat and other staple crops, are projected to decrease by between 7 and 9 per cent by 2050, significantly affecting food security in Southeast Asia. With the region’s population projected to grow by 100 million by 2050, crucial interventions are needed to counter this trend of contracting food supplies.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a promising intervention to moderate growing threats of food insecurity. Large companies, startups and research institutions are already applying AI to improve agricultural production yields and reduce waste. According to the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), AI could potentially increase farm productivity globally by as much as 67 per cent by 2050.

By using images or sensors, via mobile phones, drones or satellite imagery, AI algorithms are used to diagnose crop health, analyse soil moisture levels, project weather patterns, and identify optimal harvest timings. This empowers farmers to make data-driven decisions on irrigation, fertilisation, and pest and disease control to maximise yields and minimise wastage, thereby increasing productivity. Furthermore, AI can be used for crop monitoring and disease prediction, based on pest movement trajectories or environmental conditions, helping to alert farmers to stem crop damage. In Southeast Asia, AI-driven applications such as Dr Tania (Indonesia), AI Plant Doctor (Vietnam) and Plantix (Malaysia) are prime examples of how AI technologies can help farmers to identify plant diseases and pests, and to find treatment options. Producers have used AI to improve livestock farms, by providing recommendations to increase efficiency in operations and productivity. Pitik (a startup in Indonesia) has applied this innovation to broiler farms to help more than 500 farmers, enabling the supply of up to 5 million chickens a month for the market. In aquaculture, researchers are using AI for feed management and to optimise fish survival in Singapore.

Aside from food production, AI can aid in quality grading and the reduction of food waste by optimising supply chains through analysing transport routes and storage capacities to get food to market in good condition. Moreover, other AI periphery tools related to agricultural activities can equip agrifood system stakeholders with real-time data for the better understanding of markets, food trends, and weather patterns, so that they can make informed decisions on production plans, harvest times and pricing strategies.

Despite the immense benefits of AI-enabled technologies to food security, challenges in its adoption remain, especially amongst the smallholder farmers. Globally, 83 per cent of all farmers are considered smallholders, of which 100 million are in Southeast Asia. Barriers include the lack of digital literacy leading to lack of awareness among farmers about the availability of such tools and the high cost of adoption. A critical obstacle is infrastructural: although mobile phone access and usage are relatively high in most of Southeast Asia, the same cannot be said for internet usage and connectivity.

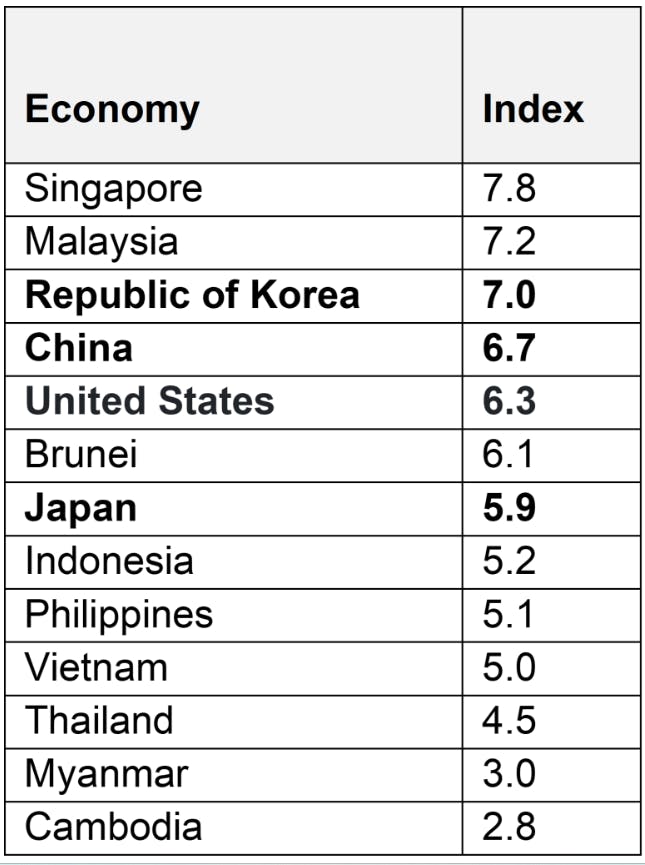

Besides digital infrastructure barriers, digital literacy is still low. Table 1 below shows a wide disparity among Southeast Asian countries as well as notable gaps between countries with lower digital literacy scores and more advanced economies.

Table 1: Digital Skills Gap Index (2021). Higher scores indicate greater digital competence. Source: Wiley; authors’ comparison of Asean member states with selected non-Asean countries (bold).

A major deterrent for AI adoption by smallholders is the cost of accessing these technologies, which is often compounded by their lack of access to finance, especially from formal sources. This is mainly attributed to factors ranging from geographical remoteness and smallholders’ absence of legal documentation with respect to land rights, to factors more closely linked to financial viability; such loan structures carry a higher risk and therefore attract higher loan premiums. Thus, even where there may be access to financing facilities, it may be too expensive or troublesome for smallholders to access finance for AI adoption.

Some quasi-governmental organisations have stepped in where private lending institutions have failed but more innovative ways may be needed. An example is One Acre Fund, a startup serving African smallholders with financing packages offering access to training and other services useful in increasing crop yields. Thus, enhancing the utilisation of these productivity-enhancing tools for this group in the region is of utmost priority.

Another emerging challenge in the use of AI-backed technologies is in the realm of ethics and governance. The risks can appear as early as during the development of an AI application, where the use of biased data in training AI models can lead to errors in the decision-making process. These can have adverse impacts on agricultural output due to the resulting miscalculations. In addition, most large language models (LLMs) are currently trained on English language data. This may be a key impediment to widespread utilisation from the get-go within this region, as Southeast Asian smallholders may not have adequate English proficiency to fully reap its features. That said, there is growing traction in the development of LLMs in other languages, including SEA-LION (Southeast Asian Languages in One Network), which is used to create LLMs for under-represented population groups and low resource languages in the region.

Data protection is another key risk as it is not clear how data is being stored and protected, nor how AI technology owners will manage personally identifiable data. This may result in violations of privacy for smallholders and their operations if data were breached. Also, the accountability aspect in AI applications by its owners is poorly established. If adverse impacts result from their use, what forms of recourse, legal or otherwise, would farmers have? These are just some of the new and dynamic risks that are important for regional policymakers to monitor and address.

The recent release of the Asean Guide on AI Governance and Ethics in February 2024 is a first attempt at addressing these risks through the establishment of a best practices framework. Though this is a voluntary set of guidelines, it makes an important first step for more regional discourse in this emerging area.

While AI holds immense potential to contribute to food security in Southeast Asia in the face of increasing climate change risks, realising its full potential requires properly laying the groundwork. This endeavour requires the collaboration of regional policymakers, agrifood system stakeholders, and technology developers working to create robust policy frameworks that can alleviate risks for technology users, especially in AI governance.

Moreover, lingering challenges must not be forgotten. The region must pay urgent attention to capacity building as well as improve access to finance so that farmers may utilise these technologies. For a start, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam have launched their national AI strategies but these are still in nascent stages, especially with regard to application in agri-food systems. Taking a multi-angle, integrated approach to overcoming all these challenges will enable Southeast Asia to reap the benefits from AI to feed its growing population while safeguarding environmental resources for the future.

Elyssa Kaur Ludher is Visiting Fellow with the Climate Change in Southeast Asia Programme, ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute. Prior to joining, Ms Ludher contributed to food policy research at the World Bank, Centre for Liveable Cities Singapore, and the Singapore Food Agency.

Kristina Fong Siew Leng is Lead Researcher for Economic Affairs at the Asean Studies Centre, ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute.

This article was first published on Fulcrum, ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute’s blogsite.