Melbourne and Adelaide have been most prone to deadly heatwave conditions among Australia’s five largest cities, according to my new research published in Climatic Change.

My study shows that between 2001 and 2015, Melbourne and Adelaide suffered the most exposure to temperatures beyond a crucial threshold of 7.26℃ above the average. Above this threshold, deaths are more likely because people are not acclimatised to the extreme weather.

I estimated that there were 151 deaths in Melbourne and 144 in Adelaide due to extreme heatwaves - those above this 7.26℃ threshold - between 2001 and 2015.

Heatwaves can cause significant numbers of deaths, especially among vulnerable groups of people who are not prepared for or acclimatised to extreme hot temperatures.

“

Heatwaves are most likely to turn deadly for significant numbers of people living in our major cities.

Even though Melbourne and Adelaide are located in more temperate areas (in comparison with more northerly cities such as Brisbane), they have been periodically hit by severe heatwaves.

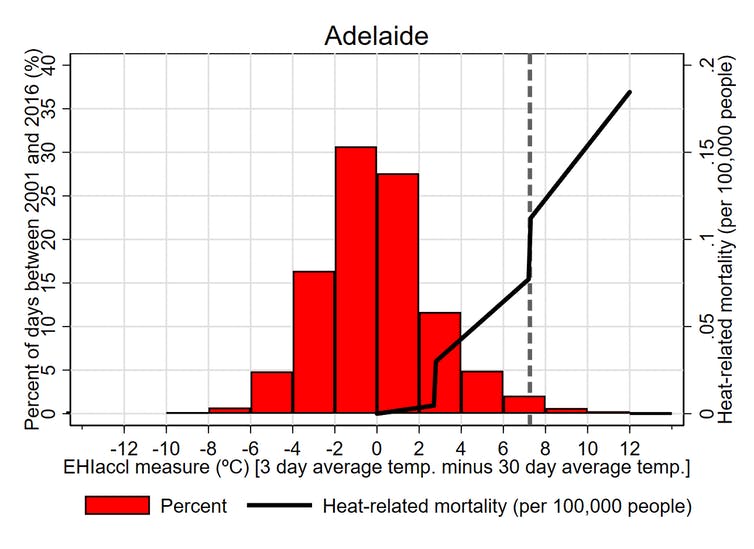

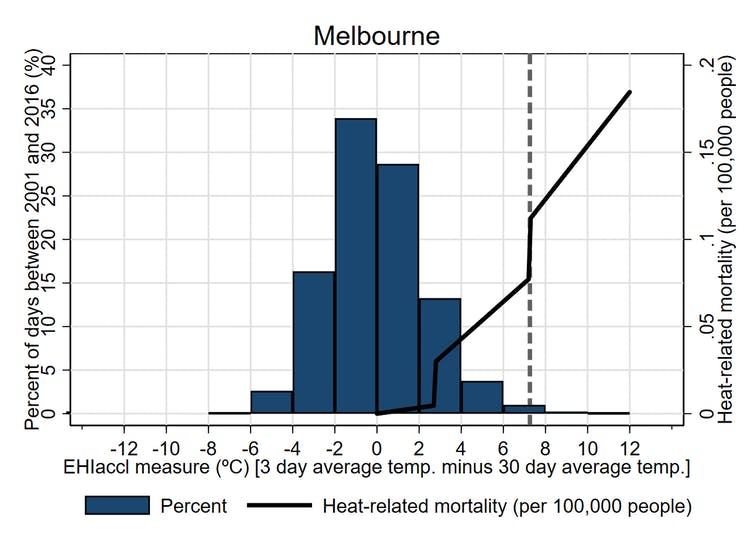

In my research, I looked at the “Excess Heat Factor”, a measure used by the Bureau of Meteorology as part of its heatwave forecasts. It is the difference between the 3-day average temperature and the 30-day average, and is therefore a measure of how “unusually hot” it is during a heatwave. It captures how much residents are likely to struggle to cope with the heat.

The graphs below show the frequency of excessively hot or cold weather for each of Australia’s major cities from 2001 to 2015. These charts show that most days had temperatures where the 3-day average was 2℃ higher or lower than the 30-day average.

A grey dashed line shows the extreme heat threshold that my study found was associated with higher deaths, relative to moderately warm and cool days. I then estimated the threshold at which there is a significantly increased risk of deaths.

The death rate (per 100,000 people) that coincides with the extreme heat acclimatisation measure is shown as a black line on each of the graphs. This is an average impact of temperature on death rates, adjusted for different cities’ population sizes and baseline death rates.

Between 2001 and 2015, most of the events above the 7.26℃ extreme heat threshold occurred in Adelaide, Melbourne and Perth. Brisbane and Sydney had fewer days above this threshold.

The importance of acclimatisation

Several previous studies have linked excessive heat to adverse events such as deaths (see here, here and here), and emergency department visits and ambulance call-outs (see here, here and here). But my study is the first to solely focus on the extreme heat index acclimatisation measure, and to identify a temperature threshold in this way. This measure is important, as it identifies the times when residents of cities with different background climates begin to struggle with the heat.

The Bureau of Meteorology does not currently use the 7.26℃ threshold identified in my paper. Doing so may improve predictions of which heatwaves are most likely to turn deadly for significant numbers of people living in our major cities.

Implications for policy

Since the severe heatwaves of 2009, many states and territories have implemented or revised their heatwave response plans, or conducted awareness campaigns to educate people about the health risks. But more can be done to make vulnerable people aware of upcoming heatwave events.

A 2016 review proposed that heatwave response plans and early warning systems should be evaluated and updated at least every five years, to ensure that they remain effective, and to incorporate up-to-date knowledge about population-level vulnerability to heat stress.

While my research has focused on Australia’s five largest cities, this does not mean that extreme heat is any less dangerous in other areas. Nor is the danger limited to prolonged heatwaves – individual hot days can catch people out too. A NSW study found that emergency hospital admissions due to dehydration and other heat-related injuries rose significantly on individual hot days, as well as during hot spells lasting at least three days.

This suggests that we need to develop more complex heat risk management plans, with targeted responses for different health issues based on the longevity of extreme heat events.

Implications for the future

We also need to consider the patterns of extremely hot temperatures that we are likely to encounter in the future. Recent research found that changes in the frequency and duration of heatwaves will be larger in the north of Australia than the south. But the same study also found that “heatwave amplitude” – the intensity of the hottest day of the hottest heatwave – will increase more in southern parts of Australia.

![]() This research suggests that cities south of Brisbane will experience the most severe temperature spikes beyond what their residents are used to dealing with.

This research suggests that cities south of Brisbane will experience the most severe temperature spikes beyond what their residents are used to dealing with.

Thomas Longden is a senior research fellow at the University of Technology Sydney. This article was originally published on The Conversation.