The amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere surpassed a level we think we haven’t seen for three million years and catastrophic consequences are sure to follow. In continuing global efforts to do something about this on an international, political level, a two-day meeting was convened in Copenhagen last week by Washington, D.C.’s Center for Clean Air Policy and the Danish Ministry of Climate, Energy and Building.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The meeting included representatives from 11 developing countries, an assortment of European countries including Germany’s International Climate Initiative, the UK’s Department of Energy and Climate Change, Norway, Belgium and the European Commission, Environment Canada, the US Overseas Private Investment Corporation and development banks.

“

UN negotiators are negotiating agreements and frameworks, while sending – via their own CDM system - a signal that pollution has no cost.

Assaad Razzouk

This Copenhagen meeting was focused on how developing countries can finance the implementation of sector-wide (or even country-wide) climate mitigation and adaptation initiatives. These initiatives, known as “NAMAs,” short for the somewhat mouthful “Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Action”, are commitments (though not necessarily binding) by developing countries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

These NAMA initiatives are extremely welcome.

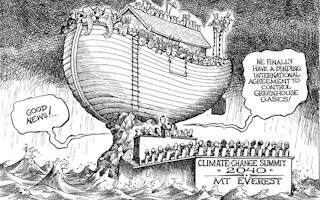

For nearly twenty years now, the United Nations has convened annual global talks under the aegis of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, an international treaty signed by nearly 200 countries to address climate change. Basically, not much happens there and countries typically agree to agree in the future.

The only material action-oriented outcome from 20 years of talks was the Clean Development Mechanism, which catalysed large funding for climate change mitigation and adaptation.

The CDM enables emission reduction projects in developing nations to sell carbon securities to developed country polluters. Buyers use the carbon credits to offset their emissions while sellers receive new investments, technologies and jobs.

According to a recent report co-authored by the Center for American Progress and Climate Advisers, the CDM succeeded beyond expectations, unleashing more than $356 billion in green investments. The CDM was on track to deliver $1 trillion in financing but is currently delivering none at all because the carbon price signal it is sending is zero. UN negotiators are negotiating agreements and frameworks, while sending – via their own CDM system - a signal that pollution has no cost.

NAMAs, in effect though not yet in law an extension of the CDM, look like the only other mechanism which could deliver tangible progress in tackling climate change.

While the CDM is project and sector-based, it is “top down” in the sense that it relies on a global offset market underpinned by the UNFCCC to catalyse finance. NAMAs are “bottom up” because they rely on developing countries taking unilateral initiatives which can rely on offsets or on other means to catalyse finance.

China, India and Brazil for example have already announced and are trying to implement sector-wide or economy-wide reductions in their emissions under a NAMA umbrella; though these announcements are voluntary in nature and non-binding.

The NAMAs we were discussing in Copenhagen were more ambitious, appear likely to be binding, may require international funding support and will have checks and balances built in. There are four reasons why developing countries should get on with it, using their own resources – without necessarily relying (or indeed, waiting) for international development funds or for donor funds.

First, most of the relative suffering from the impact of climate change is concentrated in developing countries which can’t afford to spend $50 billion in the aftermath of their equivalent of a Hurricane Sandy.

Notwithstanding the increased frequency of weather-related events in North America, China is decaying and its ecosystem is already permanently impaired. The Indian people are at the forefront of suffering from sea level rise, coastal erosion, land loss, precipitation decline and droughts. Bangladesh and the Philippines may be slowly shrinking; Bangkok and Jakarta are at risk of not existing in 50 years; and so on.

In short, from a national security perspective, developing countries cannot and should not wait for global climate change negotiations to deliver a decisive result (they probably won’t until 2020, 2030 or even never and the best we can hope for in the meantime are instruments like the CDM and NAMAs) and should forge ahead with their own mitigation and adaptation actions.

This is a moral and fiduciary obligation for politicians concerned about the well-being of their citizens.

Second, the private sector in some developing countries is wealthier and more liquid than some public purses in the West. Consequently, developing countries can implement sweeping and ambitious initiatives by enticing their own private sectors to play key funding and implementation roles. The financial liquidity pools in many developing economies dwarf the amount of potential aid available from donors such as the joint UK-Germany International NAMA Facility.

The international private sector is being left out in the cold in the fight against climate change (as I argued in May in London’s The Independent) and developing countries should avoid engineering the same outcome in their domestic markets.

The fight against climate change is a society-wide responsibility and duty. Governments should be encouraging their citizens and their private sectors to work with them.

For example, Costa Rica is in advanced preparation to launch an ambitious initiative for low carbon social housing, designated as one of its “nationally appropriate mitigation actions.” This is an initiative to build green buildings on a large scale, thus reducing consumption, waste and CO2 emissions in its construction sector; reducing energy consumption in the housing sector; improving wastewater treatment; reducing commuting through compact cities; and providing social housing to its citizens.

This should be a very attractive opportunity for the domestic, regional and international private sector, if structured with them in mind. For example, the Government can contribute land into a “real estate investment trust”, or REIT-type structure, in return for shares in the REIT. The private sector can contribute cash for its shares. The REIT would use its resources to project manage construction of the green buildings, and would own the real estate for a period of time, for example 15 years, before title passes to the recipients of the social housing benefits.

The REIT would derive income from for one or more of the sale of CDM offsets (when and if prices recover); ground rent levies; gains from the sale of parcels of land in its area; real estate taxes; a levy on energy savings; proceeds from the sale of the products generated from waste water treatments; and other sources.

“

In the same way that the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund were established at Bretton Woods in 1944 after World War II, the time has come for the establishment of a new multilateral institution: the Climate Change Action Bank.

This prescription is illustrative only, but I am confident that there are local solutions to these sector-wide emission control initiatives which can be implemented locally, with speed and impact.

Third, as I have argued in December in The Independent, the global architecture for an effective response to climate change is flawed and there is frankly no point waiting for it to deliver a magical solution. In particular, international negotiations lack a focal point, an effective organisation empowered to marshal resources on the necessary scale and to get things done.

In the same way that the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund were established at Bretton Woods in 1944 after World War II – giving rise to a new rules-based system of international finance, restoring confidence and leading to an extraordinary post-war economic boom – the time has come for the establishment of a new multilateral institution: the Climate Change Action Bank (CCAB).

Until such a focal point is established, developing countries have no choice but to get on with it: The US, the EU, Canada, Switzerland, Norway and Japan are not going to write enormous cheques in order for developing countries to fight the effect of climate change.

Fourth, these NAMAs can immediately capitalize on the enormous capacity building developed in numerous countries because of the CDM. (For a compelling overview of this capacity building tornado, see this report co-authored by the Washington, D.C.- based Center for American Progress and by Climate Advisers.)

The NAMAs can also be incorporated or linked to the CDM, in order to provide developing countries with an additional potential revenue stream, CDM offsets. While CDM offsets may be almost worthless today, that’s a function of a lack of attention by the UNFCCC to the CDM, as well a lack of demand for these least-cost abatement offsets from their designers (the UN and the negotiators).

For example, it is astonishing that the United Nations organizations fail to offset their own carbon footprint with CDM offsets, as I highlighted in a piece in The Independent. Perhaps the UN can put its money where its mouth is, that would be a welcome first step in the efforts to ensure demand recovers. CDM offsets represent the least-cost abatement option anywhere, yet currently look like a ship anchoring outside a port that hasn’t thought about providing stevedoring services.

According to a recent International Energy Agency report , “Governments should reflect the true cost of energy in consumer prices, including through carbon pricing” and it therefore makes sense for NAMAs to be developed with embedded carbon prices linked to the CDM, and at the very least the potential to generate offsets for either domestic or international use.

A bleak message emerges from this review of the progress of clean energy by the IEA: “progress has not been fast enough; large market failures are preventing clean energy solutions from being taken up; considerable energy-efficiency potential remains untapped; policies need to better address the energy system as a whole; and energy-related research, development and demonstration need to accelerate.”

Developing countries are more on their own in tackling climate change than ever before. Well thought through NAMAs can play an essential role in allowing them to take the lead in protecting the health and safety of their citizens.