Record warm temperatures above Antarctica over the coming weeks are likely to bring above-average spring temperatures and below-average rainfall across large parts of New South Wales and southern Queensland.

The warming began in the last week of August, when temperatures in the stratosphere high above the South Pole began rapidly heating in a phenomenon called “sudden stratospheric warming”.

In the coming weeks the warming is forecast to intensify, and its effects will extend downward to Earth’s surface, affecting much of eastern Australia over the coming months.

The Bureau of Meteorology is predicting the strongest Antarctic warming on record, likely to exceed the previous record of September 2002.

What’s going on?

Every winter, westerly winds—often up to 200km per hour—develop in the stratosphere high above the South Pole and circle the polar region. The winds develop as a result of the difference in temperature over the pole (where there is no sunlight) and the Southern Ocean (where the sun still shines).

As the sun shifts southward during spring, the polar region starts to warm. This warming causes the stratospheric vortex and associated westerly winds to gradually weaken over the period of a few months.

However, in some years this breakdown can happen faster than usual. Waves of air from the lower atmosphere (from large weather systems or flow over mountains) warm the stratosphere above the South Pole, and weaken or “mix” the high-speed westerly winds.

Very rarely, if the waves are strong enough they can rapidly break down the polar vortex, actually reversing the direction of the winds so they become easterly. This is the technical definition of “sudden stratospheric warming.”

Although we have seen plenty of weak or moderate variations in the polar vortex over the past 60 years, the only other true sudden stratospheric warming event in the Southern Hemisphere was in September 2002.

In contrast, their northern counterpart occurs every other year or so during late winter of the Northern Hemisphere because of stronger and more variable tropospheric wave activity.

What can Australia expect?

Impacts from this stratospheric warming are likely to reach Earth’s surface in the next month and possibly extend through to January.

Apart from warming the Antarctic region, the most notable effect will be a shift of the Southern Ocean westerly winds towards the Equator.

For regions directly in the path of the strongest westerlies, which includes western Tasmania, New Zealand’s South Island, and Patagonia in South America, this generally results in more storminess and rainfall, and colder temperatures.

“

The Bureau of Meteorology is predicting the strongest Antarctic warming on record, likely to exceed the previous record of September 2002.

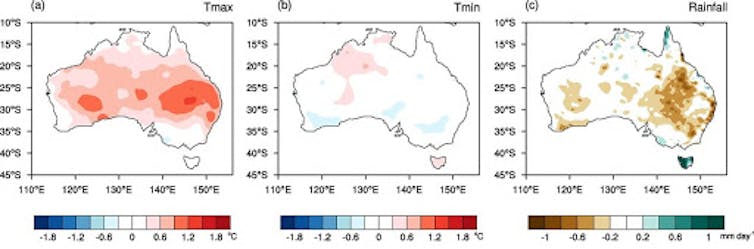

But for subtropical Australia, which largely sits north of the main belt of westerlies, the shift results in reduced rainfall, clearer skies, and warmer temperatures.

Past stratospheric warming events and associated wind changes have had their strongest effects in NSW and southern Queensland, where springtime temperatures increased, rainfall decreased and heatwaves and fire risk rose.

The influence of the stratospheric warming has been captured by the Bureau’s climate outlooks, along with the influence of other major climate drivers such as the current positive Indian Ocean Dipole, leading to a hot and dry outlook for spring.

Effects on the ozone hole and Antarctic sea ice

One positive note of sudden stratospheric warming is the reduction—or even absence altogether—of the spring Antarctic ozone hole. This is for two reasons.

First, the rapid rise of temperatures in the upper atmosphere means the super cold polar stratospheric ice clouds, which are vital for the chemical process that destroys ozone, may not even form.

Secondly, the disrupted winds carry more ozone-rich air from the tropics to the polar region, helping repair the ozone hole.

We also expect an enhanced decline in Antarctic sea ice between October and January, particularly in the eastern Ross Sea and western Amundsen Sea, as more warm water moves towards the poles due to the weaker westerly winds.

Thanks to improvements in modelling and the Bureau’s new supercomputer, these types of events can be forecast better than ever before.

Compared to 2002, when we didn’t know much about the event until after it had happened, this time we’ve had almost three weeks’ notice that a very strong warming event was coming. We also know much more about the process that has been set in train, that will affect our weather over the next one to four months.

Harry Hendon is a senior principal research scientist at the Australian Bureau of Meteorology. This article was originally published on The Conversation.