Singapore became the first Southeast Asian country to launch a carbon tax when the bill was passed in Parliament in March. Since the bill was first mooted, environmentalists, industry and academia have weighed in on the pros and cons of the tax, which will take a hybrid carbon tax and credits form.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

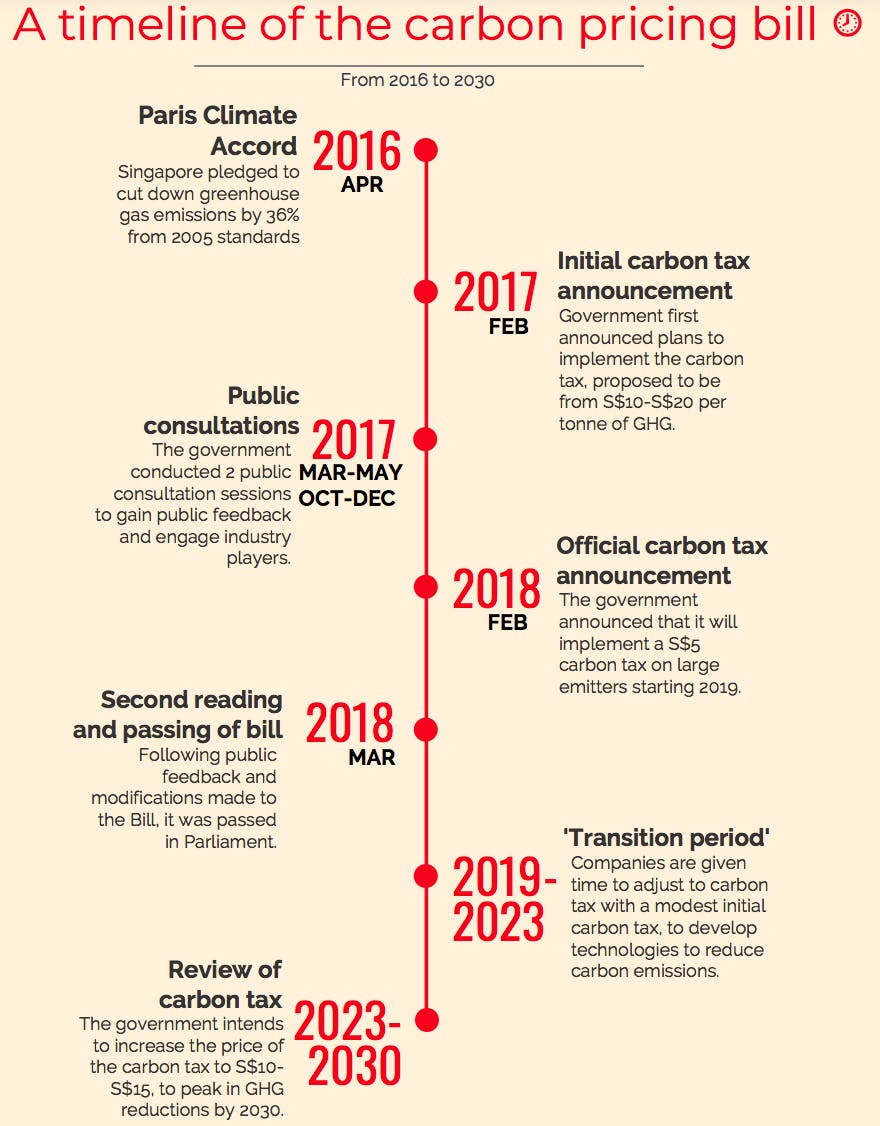

Initially proposed at a price of S$10-$20 per tonne of CO2 emissions, the city-state’s Minister of Finance, Heng Swee Kiat, announced that the tax will be implemented at a lower price of S$5 per tonne before gradually being increased to between S$10 and S$15 per tonne.

Following rounds of consultation with the public and industry, it was clear that one priority was preventing a drastic fallout by the battered power generation sector, which had voiced concerns about the new tax.

A spokesperson from the Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources told Eco-Business that the S$5 per tonne price was to “give companies more time to adjust to the impact of the tax”.

But is the bill, in its current form, ambitious enough for a decarbonising world?

A brief timeline of the carbon pricing bill. Image: Eco-Business

The ‘softly, softly’ tax rate neither satisfies pro-business sentiments opposed to any tax, nor lives up to the the tax’s very purpose of decarbonising Singapore’s industries.

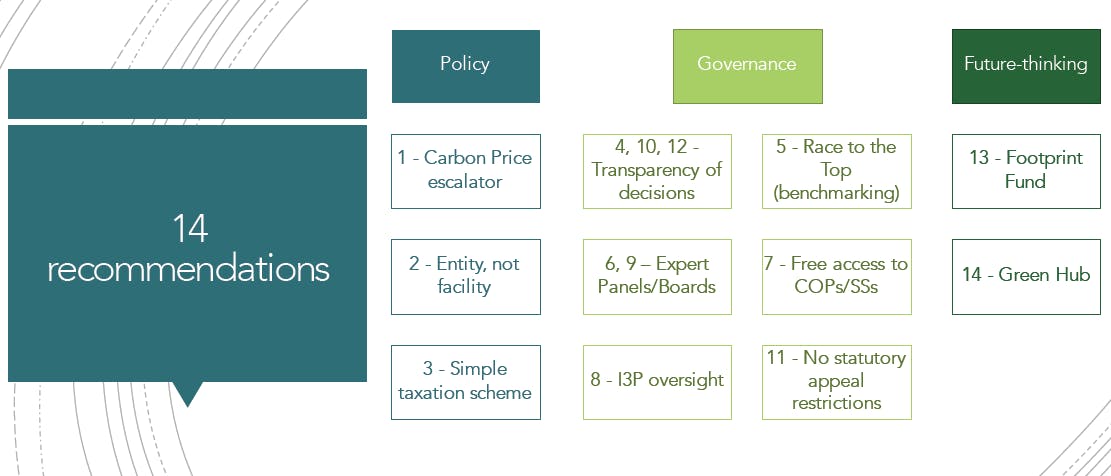

Perhaps this is why we have heard concerns from eight Members of Parliament, across political affiliations. University students have made their own recommendations for changes to the bill, including the creation of a fund to invest collected taxes in further emissions-reduction schemes. The public has been consulted and raised their own questions, and an academic has questioned if the tax is “too small a step in the right direction“.

Here are some of the points of contention.

Is the carbon price too low?

Yes, yes and yes, said the public, students and even businesses with the most to lose.

Feedback gathered through a public consultation last year called for a higher tax rate over time, and surprisingly, petrochemicals giant Shell argued that the tax is not enough to encourage energy efficiency.

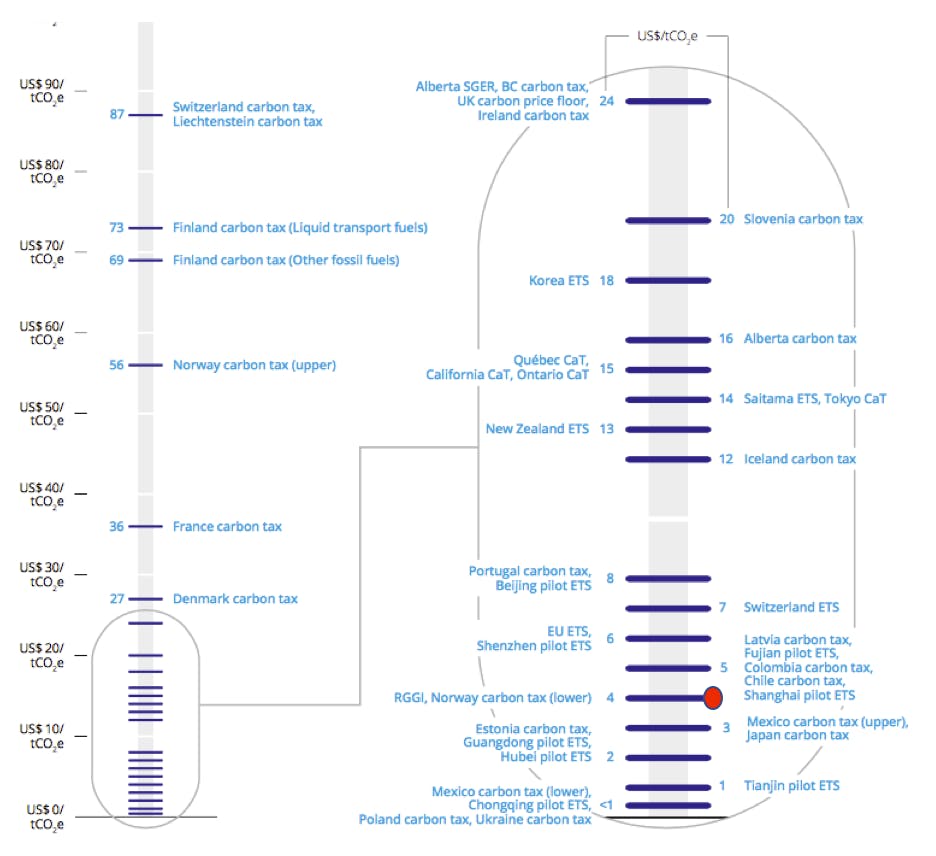

A report published by the Environmental Law Students Association (ELSA), called for a “carbon price escalator” with S$5 annual increments in the tax rate, arguing that Singapore’s initial price of S$5 is too far off from the benchmark of US$50–US$100 per tonne of emissions recommended by World Bank’s High-Level Comission on Carbon Prices report.

The government’s response has been unchanging, reiterating the need to strike a balance between economic and environmental considerations, and not to compare Singapore’s carbon price bill with other countries as the city-state does not exempt any sectors.

However, while exemptions may in effect mean lower carbon taxes in other countries, this does not change the fact that Singapore’s S$5 tax, or US$3.80 at time of writing, is on the lower end of the spectrum of global carbon tax rates.

The red dot indicates the standing of Singapore’s existing carbon price (nominal) internationally. Image: World Bank Group

Is the carbon tax bad for business?

A pressing concern is that the carbon tax will increase the cost of operations and dampen business competitiveness.

This includes not just the direct cost of investing in greener technologies, but also the indirect costs of auditing and reporting involved in a carbon tax system. In particular, this may affect the export competitiveness of Singapore’s industries, especially the export-intensive petrochemical industry.

“

To reach Singapore’s Nationally Determined Contribution under the Paris Agreement…the public has to engage in dialogue with the government and shape the carbon tax that reflects Singapore’s ambition.

Minister for the Environment and Water Resources, Masagos Zulkifli, said that it makes business sense for companies to start pricing the cost of emissions into operations given the growing trend towards decarbonisation of the economy. “Companies ignore these realities at their peril,” he said in Parliament.

He reassured his audience that the inception rate of S$5 for the first five years serves as a “transition period” for companies to adjust to the tax. The government is also prepared to spend more than the estimated S$1 billion in carbon tax revenue to help companies to reduce emissions.

Do we know enough about the carbon tax?

What are the emission rates of the 30 to 40 companies affected by the carbon tax? What is the likely impact of the carbon tax on the amount of emissions produced by these companies?

Leon Perera, non-constituency MP, urged the government to consider making emissions data public to allow increased research, scrutiny and added pressure on companies, during a parliamentary session debating the bill. Acknowledging concerns about commercial sensitivity, he said these can be addressed by releasing emissions data in clusters or by industry.

Recommendations by ELSA students likewise called for emissions data to be released publicly in order to facilitate consumer choice and for market players to have a benchmark to work with.

14 recommendations proposed by university students of the Environmental Law Students Association. Image: Environmental Law Students Association

Will households foot the bill for the tax?

Meanwhile, members of the public have wondered how much of the carbon tax would trickle down to the common household as companies pass on the costs to consumers.

The government has said that the tax is estimated to result in a one per cent increase in cost of total electricity and gas expenses for households, but that the difference could be offset by rebates of S$20 per year, for eligible households.

However, the accumulative effect of the rise in cost of living across various policies, including the carbon tax, water price hikes and GST hikes, will add up given recent budget announcements, said MP Lee Bee Wah in Parliament.

But in line with the aim of the tax to decarbonise Singapore, this could in turn encourage households to save electricity and reduce their emissions.

What lies ahead

As the bill exits parliament, it will enter conversations on the streets and in offices.

The rate of the tax is fixed until 2023, but other policy details remain up in the air including the transparency of data and whether the S$10-$15 price will be imposed in 2023.

Given broad support for a carbon bill and the accelerating effects of climate change, the government should seize the chance to implement a more ambitious carbon tax.

To reach Singapore’s Nationally Determined Contribution under the Paris Agreement—to reduce emissions intensity by 36 per cent from 2005 levels by 2030, and peak carbon emissions by 2030—the public has to engage in dialogue with the government and help shape a carbon tax that reflects Singapore’s ambition.

Preferably into something with more bite than a five-dollar-bill.

Tan Jing Ling is a writer at Eco-Business.