In June this year, Britain’s largest asset manager Legal & General announced that it would remove Japan Post Holdings (JPH) from its $6.7 billion Future World index funds. It added that any of its funds that still held shares would be instructed to vote against the re-election of JPH’s chairman. L&G justified the move by saying that JPH had “shown persistent inaction” to address climate risk.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

JPH was reportedly shocked at L&G’s initiative, which came after a year of L&G quizzing managements of leading companies on their climate policies. In truth, it should not have been very surprised. Pressure on global financial institutions from US and European activist groups to divest from “extreme carbon” such as coal and oil sands has been building for over a decade. Inevitably, once Western financial institutions began divesting from their own funds, they would also evaluate the policies of their investments, regardless of which country they were located.

In the US, JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Citi, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs have all announced coal exits. BNP Paribas, AXA, Allianz, RBS, Munich Re, ING, Rabobank, Standard Chartered and HSBC are among the institutions that have made similar moves in Europe.

The reason? High profile and often embarrassing campaigns by determined environmental activists to make them change policies, initially targeting US college endowment and pension funds and their fund trustees and professional investment advisors. These campaigns were modelled on the politically charged campus divestment battles of the 1980s which were intended to undermine the economy of apartheid South Africa. Although they achieved little in financial terms, they helped to make South Africa a pariah investment in the USA for many years.

In this way an non-governmental organisation-driven campaign made in America, endorsed by a financial institution in Britain, can end up punishing a major institutional investor in Japan.

The ‘global ripple’ of NGO campaigning that discomforted JPH is unlikely to stop at carbon. Western activists have learnt from the climate divestment movement that support from sympathetic financial institutions is a highly effective way to give a campaign “bite”.

“

Asian firms need to look hard at all their investments, including those in places with weak or non-existent NGO movements, to check if they are responding appropriately to the pressures already forcing change elsewhere in the world, or likely too, to avoid becoming unexpected targets of NGO campaigns.

One reason for the greater role of financial institutions is the ‘mainstreaming’ of ethical and sustainability concerns by investment funds and banks. Once the preserve of socially responsible investing and clearly denominated ethical funds, exclusion policies on climate change and carbon, environmental and social governance have been adopted by most leading financial institutions. Just last week, the world’s largest asset manager BlackRock announced that it is to launch a range of exchange-traded funds focused on environment, social and governance (ESG) factors in the US and Europe. Meanwhile in the vanguard of this movement, investors like L&G are behaving increasingly like activist investors, lobbying companies to raise sustainability standards and threatening to vote down managements or divest should they refuse.

It is also now commonplace for financial institutions, especially those in Europe but increasingly in the US too, to consult with NGOs before drafting or revising policies on environmental and social issues. NGO support for reforms is actively sought and NGO criticism is taken seriously, right up to board level.

Much of this change in attitude by financial institutions is in reaction to pressure from political stakeholders and customers. The 2008 crash left banks bereft of public sympathy and deserted by political friends. Beefing up ESG policies and engaging with NGOs was an obvious way to recover some of their reputation. Asian financial institutions need to start doing the same, if they are to avoid being caught on the wrong side of increasingly fierce arguments concerning rapid economic development, such as agriculture encroaching on wilderness and self-determination for indigenous peoples.

Sustainability, human rights, labour standards and even animal rights will become more important for global financial institutions, as they develop ever more expansive policies and standards under pressure from NGOs and other stakeholders. This will have big implications for the firms and industries in which these institutions invest, wherever they are in the world.

Another area where investors are going to be increasingly exposed is plastics. Two years ago, plastic pollution had barely registered on the public consciousness. Today it is a major public concern, getting heavy media coverage, persuading governments to draw up legislation on plastic waste and companies to rethink their packaging and single-use plastics policies.

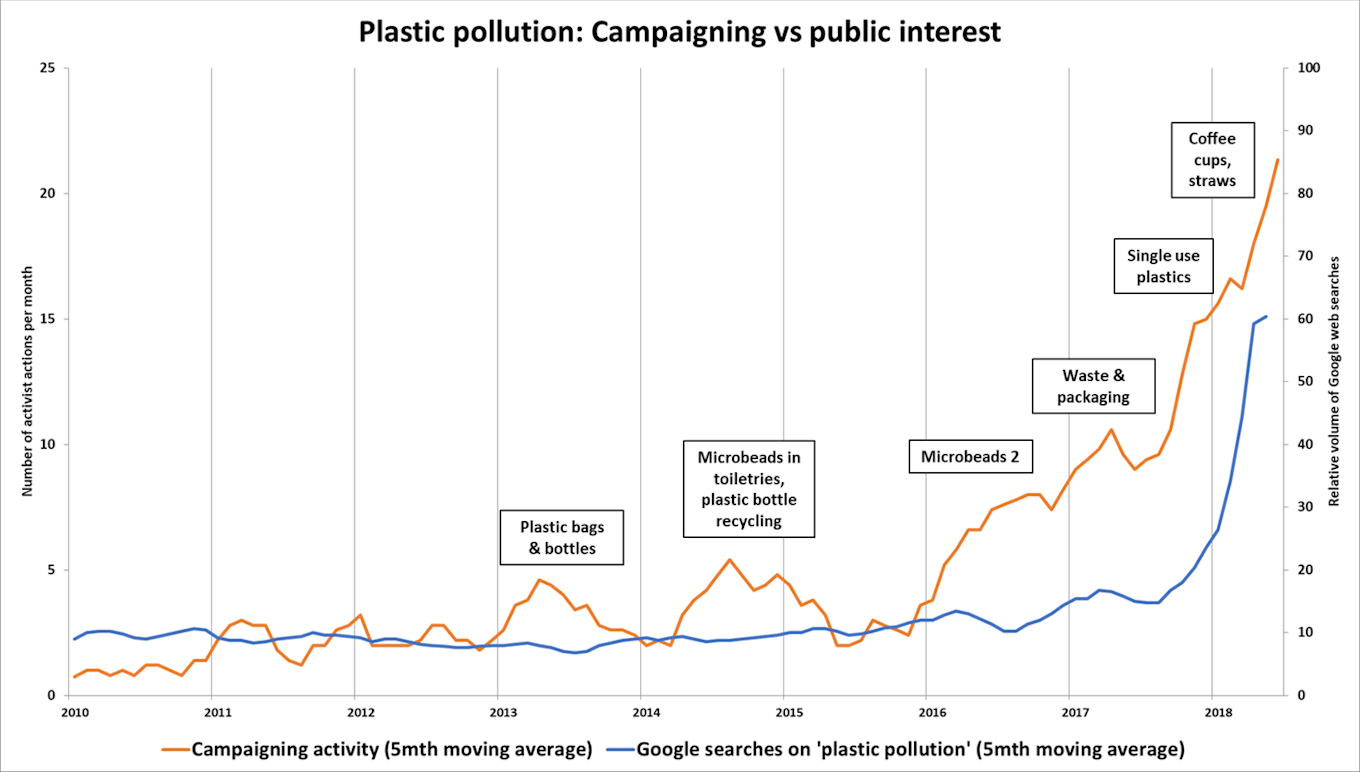

The chart (Chart 1) shows how through successive focused campaigns the plastics issue jumped massively in public awareness (as measured by the relative volume of Google searches) within months of a major uptick in NGO campaigning led by Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth.

Comparing level of NGO campaigning and public interest in the plastic pollution issue. Image: Sigwatch

A similar predictive association exists between campaigning and subsequent public anxiety on shale gas (fracking) in the US, and the environmental impact of meat consumption. NGOs make the political weather on many issues. This power is now combined with a capability to project influence globally through supportive financial institutions. Asian firms need to look hard at all their investments, including those in places with weak or non-existent NGO movements, to check if they are responding appropriately to the pressures already forcing change elsewhere in the world, or likely too, to avoid becoming unexpected targets of NGO campaigns.

Without doubt, nearly all the momentum behind these campaigns is coming from Europe and North America. In most of Asia, NGOs are small and ignored (Australia, New Zealand and to some extent Hong Kong are the few exceptions).

But the Japan Post Holdings case shows that this does not make Asian businesses immune from NGOs, and certainly not from the consequences of their campaigns.

Robert Blood is managing director at Sigwatch. This article was written exclusively for Eco-Business.