Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr, only son and namesake of the late Philippine dictator, won a hotly-contested presidential election in May, after campaigning on a promise to unify the country, boost jobs, and tame spiraling commodity prices borne out of Covid-19 recovery and a war in Europe.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Marcos Jr has been open about putting renewable energy on top of his agenda, even capitalising on the use of the Bangui wind farm in his hometown of Ilocos Norte for a television advertisement during his presidential bid.

In his inaugural speech, he scorned the “rich world” for not doing enough to curb their emissions, leaving climate-vulnerable nations to pay for natural disasters they had contributed so little to, something none of his predecessors have done in the recent past.

Eight months after he took office, Eco-Business examines if he has remained true to his commitments and what policies may be needed for him to steer the country towards its low-carbon ambitions.

1. Renewables to take centre stage instead of gas

San Miguel Corporation’s liquified natural gas (LNG) plant being built along the Verde Island Passage in Batangas, Philippines. Despite the department of agricutlure’s “cease and desist” order, it is unclear if the project has indeed halted construction. Image: Basilio Sepe

Marcos Jr proclaimed clean energy to be top of his climate agenda, but he has likewise been vocal about tapping natural gas as a “bridge fuel” while the country was developing renewables.

Although the government ordered to halt construction of two gas plants in August due to legal issues, it approved three others—Philippine-owned First Gen Corp, Singapore-based Atlantic, Gulf and Pacific, and Australia-listed Energy World Corp—poised for commercial operations within the first quarter of this year.

The three terminals are among six such projects that the energy department has approved. Three more are expected to come online within the next three years, including a project proposed by Anglo-Dutch oil major Shell.

The development of liquified natural gas (LNG) is in full swing, as the nation ramps up the infrastructure to support the import of the fossil fuel to augment the declining reserves of the Malampaya gas field, the country’s only domestic source of fossil gas, set to run dry by 2027.

Apart from gas, Marcos Jr has spoken about his plans to revisit the shelved Bataan Nuclear Power Plant (BNPP), which was built during the presidency of his father. He also met with United States Vice President Kamala Harris about a civil nuclear energy cooperation deal on her first official trip to Manila in November.

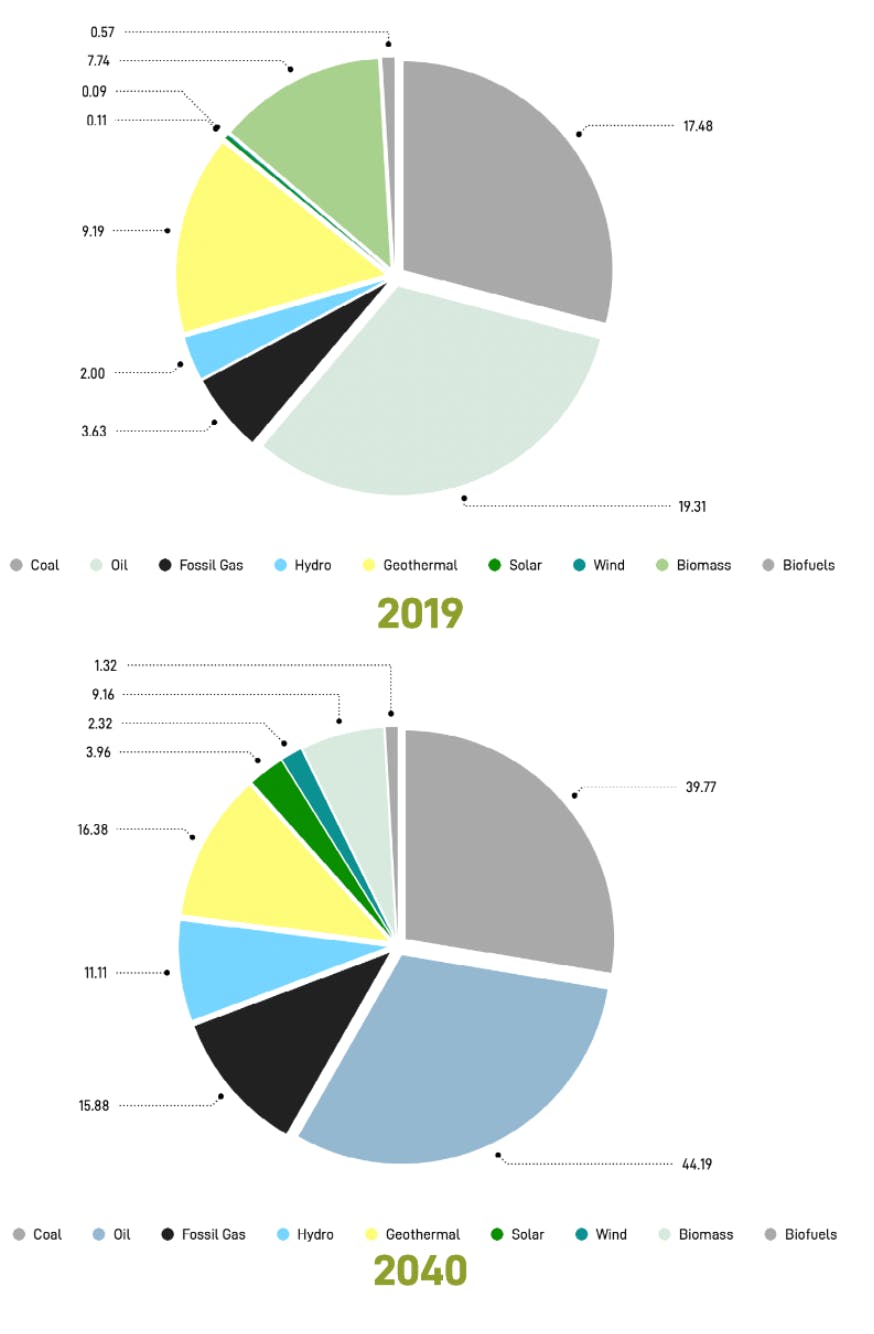

Fossil gas has a meager share of 6 per cent in the country’s total energy mix, equivalent to 3.63 MTOE (mega tonnes of oil equivalent), but this is expected to change as the government’s natural gas roadmap intends for it to comprise 11 per cent of the country’s total primary energy supply by 2040. Image: CEED

In contrast, there has been scant information on what Marcos Jr is proactively doing to boost renewable energy investment. The energy department did raise the minimum renewable energy capacity from 1 to 2.5 per cent in the power mix to encourage more investors and end-users to develop and utilise domestic energy sources.

“Competitive renewable energy zones” (CREZ), or areas in the archipelago identified to be rich in clean power potential, were supposed to be tapped for clean energy investment but the department of energy confirmed with Eco-Business on Friday that there is no update on development in these zones.

If the chief executive does not put as much emphasis on long term solutions like renewables and invests more on what he calls an interim solution like gas or untested technologies like nuclear, the country will fail miserably to attain its target of utilising 35 per cent clean power by the end of the decade.

Studies have also found how liquefied natural gas (LNG), which is being pitched as a reliable and affordable bridge fuel to transition from coal, is not expected to help ease high power costs in the Philippines, with supply constraints and high prices expected to continue in the next few years.

There are also no government-backed power purchasing agreements (PPAs) or guarantees, which could leave investors highly exposed to market risks, as they have no guarantee of a sure buyer of their electricity. Projects could run the risk of turning into “stranded assets”, where there is not enough cash flow to cover the debt, leading to bankruptcy for the investor.

2. Raw minerals for the green economy, not for the family’s

The president made his first state visit to China last week. Before he departed for Manila, he disclosed that he won almost US$22 billion worth of investment pledges from the host nation, with funds including those related to the production of minerals, battery, and electronic vehicles (EVs) in the Philippines.

Before Marcos Jr should secure deals with investors to supply the raw minerals needed for EV batteries, he has to ensure that new and existing mines in his country do not violate forest zoning laws and encroach on vulnerable communities.

The Philippines has the world’s fifth-largest reserves of nickel, one of the mineral commodities in demand to manufacture EVs. A total of 46 new mining applications for nickel have been submitted to the government since the lifting of the nine-year moratorium on granting new mining permits was issued in April.

An Indigenous community at the foot of Mount Bulanjao in Palawan. The Environmental Legal Assistance Center, a non-profit composed of environmental lawyers, filed a case against the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development for granting a permit for the Rio Tuba nickel mine to expand on the mountain. Image: Eco-Business

Some applications and expansions are under contention such as the Rio Tuba Mine project in a mountain that was previously marked as a “no-take zone”, or restricted areas where no extractive activity is allowed.

A group of environmental lawyers filed a case last year against the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development, an agency in charge of zoning forest areas, for granting permits for this expansion.

Aggressive approval of mining permits may put in jeopardy the communities who will be affected by forest removal and water contamination brought about by firms in a hurry to meet demand from China, the Philippines’ major buyer. And, perhaps, in a hurry to reap the benefits of being in power.

Environmental advocary group Kalikasan released a press statement protesting the installation of Martin Romualdez (left) as house speaker. Imaage: Kalikasan PNE

The president backed his first cousin, Martin Romualdez, to be elected as speaker of the house of representatives, the fourth highest official in the land, who is able to sign laws and resolutions, as he presides over sessions in congress.

Romualdez is tied to the mining industry. He is son of the late Benjamin Romualdez, former president and chief executive officer of copper and gold mining behemoth Benguet Corp.

Romualdez’s son sits on the board of directors of nickel mining firm Marcventures Holdings. The congressman himself set up a mining subsidiary last year worth US$2.7 million.

Among Marcos Jr’s staunchest allies in his cabinet are a troop of officials with high stakes in the mining sector. Senator Cynthia Villar, chair of the senate committee on environment and natural resources, and her son Senator Mark Villar, own Prime Asset Ventures Inc, the parent company of TVI Resources Development Phils. Inc., which produces nickel. Senator Sherwin Gatchalian has a family-owned business The Wellex Group whose mining subsidiary extracts nickel and limestone.

With his closest family and colleagues as big players in mining, Marcos Jr should be on his toes as he navigates his way around what is best for the green economy, not for his allies.

3. Investment in high tech solutions to lower rice costs

Marcos Jr appointed himself as agriculture chief to give himself direct responsibility for food output as inflation pressures challenged his incoming administration. He was primarily focused on lowering the price of rice—the staple found in nearly all the dining tables of every Filipino.

At the height of the holiday season, he announced how the government was getting closer to the goal of bringing down the price of rice at 45 cents per kilo, by putting a price cap on it.

However, according to fact-checker Vera Files, the price of the National Food Authority, the agency that sells rice to government institutions and wholesale outlets, was at that amount, but the department of agriculture still pegged rice costs in Metro Manila at 68 to 90 cents a kilo.

Marcos Jr must look at technologies to spur rice production to keep costs down. The first time he addressed the nation, he talked about how determined he was to revitalise the agricultural sector in a bid for “sustained scientific farming”.

Marcos Jr with IRRI Director General Jean Balié followed by a tour inside the International Rice Genebank, a facility which contains the biggest collection of rice gene diversity in the world. Image: CGIAR

As agri chief, he visited the headquarters of agricultural research and training organisation International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in Laguna in November where he was briefed about various initiatives to improve crop resilience.

At the end of the visit, all he said was that the IRRI “gave him hope” in terms of the available technologies the country has for the agriculture sector, but gave no mention of any government plans to boost supply.

The Philippines became the world’s biggest rice importer in 2019 with purchases estimated at a record 2.9 million tonnes, despite the IRRI being based in the country.

Food prices in the archipelagic country are not competitive because of a lack of transport, science and technology available to farmers who have limited access to infrastructure and telecommunications systems that can help them reduce the cost of fuel, seeds, labour, fertiliser and pesticides.

4. Seeking climate justice by leveraging on the Philippine Commission on Human Rights landmark report

The president could do more to address climate disasters in the country by seeking climate justice from big polluters, as he said he would when he was sworn in as the country’s 17th president in May.

He ascended to power only days after the Philippine Commission on Human Rights (CHR) released its report that found that there are legal grounds to hold the world’s biggest fossil fuel companies liable for climate disasters.

The report concluded a four-year investigation by the CHR with a landmark resolution that 47 fossil fuel companies, including energy giants Shell, Chevron, ExxonMobil, Total, and BP, contributed to 21.4 per cent of global emissions.

Instead of using this study as the basis for seeking climate justice, he has been missing in action when typhoons strike. He was nowhere to be found during the December shear line rains, a weather phenomenon that results from cold and warm winds, which have resulted in dozens of deaths across the country. When asked if he would visit the areas after his state visit to China, he responded “probably”.

When Typhoon Noru slammed into the Philippines in September, he drew criticism for being insensitive to Filipinos by going to Singapore over the weekend for the Formula One Grand Prix.

Marcos Jr has made at least an effort to include climate change in the conversation more than any Philippine president has in this lifetime. Let’s hope the conversation will translate into actual policies decisive and effective enough to allow him to finally step out of his father’s shadow.