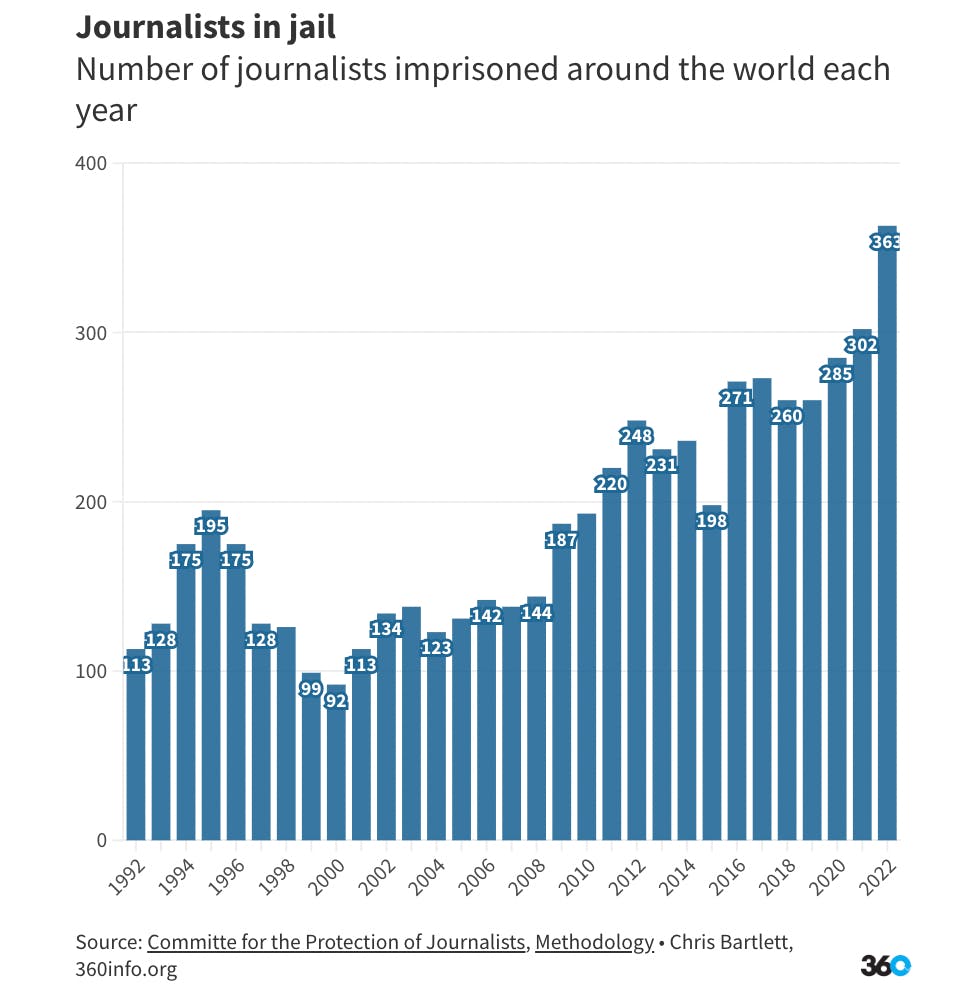

As we mark the 30th anniversary of the World Press Freedom Day, there is one number that tells us a lot about the state of press freedom globally: 363. That’s how many journalists were in prison across the planet as of December 1 last year, according to a snapshot by the Committee for the Protection of Journalists.

Since then the number has risen, most notably with Russia’s arrest and jailing of the Wall Street Journal‘s Moscow correspondent Evan Gershkovich on spying charges. “Evan is a member of the free press who — right up until he was arrested — was engaged in news-gathering. Any suggestions otherwise are false,” the Journal has said in a statement.

The number of detained journalists is alarming for several reasons. First, it is a record by a significant margin. The previous year it was 302 (also a record). Apart from a few minor dips, it has been steadily increasing since 2001. This latest number is almost three times higher than what it was when World Press Freedom Day was first announced 30 years ago, and four times higher than the lowest point at the turn of the millennium. And remember, the World Press Freedom Day was set up to help defend a principle widely recognised as a cornerstone for any functioning democracy.

Number of journalists imprisoned around the world each year. Source: 360info

The reason things deteriorated so badly at a time when democracies are supposed to be advancing partly lies in two other numbers, and the story behind Evan Gershkovich’s detention.

The first number, 199, refers to those journalists who’ve been imprisoned on what the Committee for the Protection of Journalists describes as ‘anti-state’ charges. That’s things like sedition, treason, espionage, breaches of national security, and terrorism. Although the statistics are too crude to say exactly why that is the case, all the signs point to 9/11.

Soon after Al-Qaeda launched its attacks on that horrific day, then-US President George W. Bush declared the ‘war on terror’. At the time, with the dust still settling on the wreckage of the Twin Towers, few people quibbled with the semantics, but one colleague presciently quipped that Bush had just declared war on an abstract noun.

Unlike so many conflicts of the past, the war on terror was a battle not so much over tangible things like ethnicity, land or water, where journalists are witnesses rather than participants. Instead, it was a fight over ideas – a struggle between liberal democracy and Islamic theocracy. In that kind of war, the battlefield extends to the place where ideas themselves are transmitted, in other words, the media. This idea is much less abstract than it sounds.

In the post-9/11 world, terrorism and national security became touchstones for politicians everywhere. They gave governments a licence to pass a host of draconian laws that strengthened state power beyond physical things like lives and property, into control over information and ideas. They did that by loosening the definitions of what constituted ‘terrorism’ and ‘national security’. In Egypt for example, human rights groups accused the government of using terrorism as an excuse to pass a suite of laws that have then been used to shut down anyone who criticises the government, and lock up journalists who talk to those critics.

In 2020, the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights and counter terrorism, Fionnuala D. Ní Aoláin, said: “The intersection of these multiple legislative enactments enable increasing practices of arbitrary detention with the heightened risk of torture, the absence of judicial oversight and procedural safeguards, restrictions on freedom of expression, the right to freedom of association and the right to freedom of peaceful assembly.”

She could have been speaking of any of the world’s most prolific jailers of journalists. Iran currently tops the list, imprisoning dozens mostly for covering the ongoing protests over head scarves. China is next, going after reporters who’ve tried to cover the government’s crackdown on the Uighur community in Xinjiang province. And ever since a failed coup in 2016, Turkey has also been enthusiastically imprisoning critics and journalists on terrorism charges.

The other deeply troubling figure is 86 per cent. That is the proportion of journalist murders around the world that remain unsolved. Consider that for a moment. Almost nine out of 10 killers of journalists are free and unpunished.

It is always going to be hard working out who is responsible for killing a journalist on a front line with a rocket much less hold them to account, but in its most recent report on the issue (from 2022), the UN calculated that 78 per cent of journalist murders happened off the clock, away from work, in the streets or at home, sometimes in front of their families.

That number for impunity makes it very difficult to escape a chilling conclusion: the authorities are generally either directly involved, or simply don’t care enough to seriously investigate. And either way, the effect is the same – reporters brave enough to keep working have tended to opt for the safe, easy stories, smothering serious scrutiny of the actions of the powerful.

As someone who has lost far too many close friends and colleagues, and who has spent time in prison on terrorism charges, I have an obvious personal interest in speaking out about the murders and detentions of journalists. But this is not about me and my fellow reporters.

One thing autocrats clearly understand is that the first step in controlling the public is to control the flow of information. That is why the first place to send your tanks in any coup is the local TV broadcaster; and why throwing a few journalists behind bars is always the start of a general crackdown on dissidents and critics.

It is also why Evan Gershkovich is in so much trouble. In March, he travelled to the city of Yekaterinburg for a story about the attitudes of Russians to the war in Ukraine and the private military contractors, the Wagner Group.

It was a risky assignment given the increasingly toxic relationship between Moscow and Washington over the Ukraine war, but the talented 31-year-old American reporter knew the country well, and no foreign journalist had been detained in Russia since the end of the Cold War.

His trip was short. Soon after he arrived in Yekaterinburg, Russia’s domestic intelligence service, the FSB, announced he’d been arrested and charged with, “espionage in the interests of the American government”. He was last seen on April 18 in a Moscow court where his appeal against detention was denied. He appeared calm and was pictured smiling. Marks on one of his wrists appeared to show where he had been kept in handcuffs.

Gershkovich, his newspaper and the US government all vigorously deny the allegations, and it now seems clear he has become a pawn in a wider struggle. By imprisoning a high-profile American journalist on spurious espionage charges, the Russian authorities have achieved three goals.

First, they’ve acquired a bargaining chip they can use to extract concessions from the US government. Second, they can use the journalist as ‘proof’ of American perfidy in Russia. And finally – and perhaps most disturbingly – they have sent an unequivocal message to every journalist working in the country: If you cover us critically, you too will find yourself in prison. With the Journal’s correspondent now facing decades behind bars, that country has suddenly become much darker.

Professor Peter Greste is a former foreign correspondent who spent 25 years working for the BBC, Reuters and Al Jazeera. In December 2013, he and two of his colleagues were arrested in Cairo and charged with terrorism offences. In letters smuggled from prison, he described the arrests as an attack on media freedom, and was released after more than 400 days. He is now a professor of journalism at Macquarie University and a founder of the advocacy group, the Alliance for Journalists’ Freedom.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.