On 11 September 2023, riots broke out in Batam City, which resulted in many victims of violence including the protesters, the police and even BP Batam’s (Batam’s free trade zone and free port authority) security personnel.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The police arrested 43 protesters as this series of riots proved to be the worst in Batam City since racial riots occurred between local workers and foreign workers in 2010.

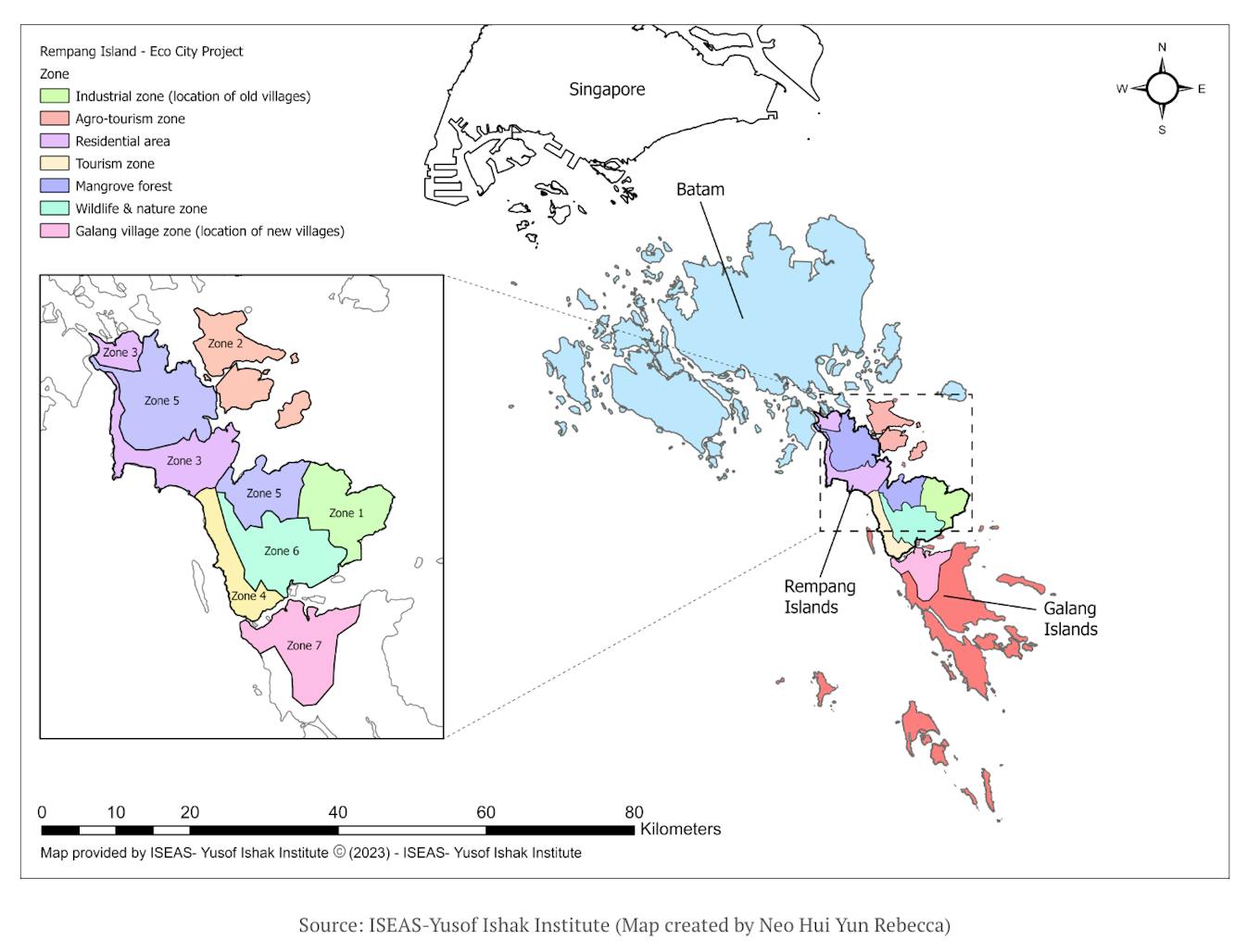

This latest conflict was triggered by a plan to clear land to develop the Eco-City industrial and tourism area on Rempang Island (see map below), just 3 kilometres from Batam Island.

PT Makmur Elok Graha (MEG), the owner of the land rights, is expected to build a glass and solar panel factory with the Chinese Xinyi Group’s investment. This development became the central government’s focus after President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) visited China at the end of July.

Map of Batam and Rempang Islands

Rempang’s Eco-City was upgraded to a national strategic project based on the Minister of Economic Affairs’ Regulation No. 7 of 2023. The project is expected to bring a total investment value of 381 trillion rupiah (US$25 billion) till 2080.

For project development, the residents of Rempang Island have been asked to move from their land to a location to be determined by BP Batam. BP Batam originally targeted this relocation which involves around 700 affected families to be completed by the end of September 2023.

Residents who have lived for generations on the land have rejected the government’s offer to move to a new location. For the residents, the land is considered customary land, referred to as their “old village” (kampung tua). The government is offering compensation for a “type 45” house valued at 120 million rupiah (US$7,800) and a land area of 500 square metres.

The government will also exempt relocating residents from their housing rental costs during the construction of new housing as well as offer them financial support of 1 million rupiah per head of the family. The residents consider this compensation inadequate and criticise the government for deciding on the plan unilaterally, and have rejected the offer. Their anger led to the rejection of the planned investment and demonstrations.

The shifts in land use on Rempang Island reflect regulatory uncertainty regarding land use in Indonesia more generally.

The current investment plan on Rempang Island can be traced back to the early 2000s. In 2002, BP Batam and the city government signed an investment agreement with PT Makmur Elok Graha (PT MEG), a subsidiary of the Artha Graha Group, owned by conglomerate Tomy Winata.

The agreement grants land management concession rights to PT MEG but PT MEG did not implement its investment plans until recently. During this period, there was a shift in the land’s function, including people occupying commercial land for residential purposes. This was allowed by the regional government because the investment plan was previously unclear.

The shifts in land use on Rempang Island reflect regulatory uncertainty regarding land use in Indonesia more generally. The Minister of Agrarian Affairs and Spatial Planning Hadi Tjahjanto has said that the land occupied by residents did not have an ownership certificate.

The Coordinating Minister for Political, Legal and Security Affairs, Mahfud MD, stated that the recent incident in Rempang was caused by the decision of the local government and the central government, in this case the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, to change the functional status of the land. This regulatory uncertainty created a conflict between the locals and the government.

The plan of the central and regional governments to develop the Eco-City industrial area does conflict with the interests of the Malay community alliance in the Riau Islands. While the Malay community alliance has emphasised that they are not anti-investment, they firmly reject the eviction of 16 old Malay villages on Rempang.

They reason that Kampung Tua Melayu (the old Malay village) is historically important to the indigenous community and that this eviction will eliminate their traditions.

This latest violence shows that the central and local governments need to improve their approach towards local communities. The involvement of the Indonesian army and the forceful actions of police and security forces in dealing with the demonstrators have caused more fear and anger. For instance, BP Batam’s efforts to socialise the Eco-city project through social media were not effective.

The community is doubtful about the benefits of establishing a Kampung Baru (new village) for their community and is worried that their rights will be taken away vis-à-vis their existing land. These doubts are understandable, as the villagers have not seen any housing or facilities constructed in the place to which they are supposed to relocate.

The conflict in Batam could significantly impact the investment climate in the Riau Islands if further violent demonstrations break out. Investors need political stability and security for their investments. Admittedly, demonstrations that lead to violence or strikes are nothing new in Batam City.

According to a study by Francis Hutchinson, periodic demonstrations and strikes have hurt investor sentiments. In 2011, workers slowed down and demonstrations cost Batam US$10 million in revenue. This civil disturbance repeats itself every year, resulting in some investors leaving Batam completely.

This is detrimental to the local economy, which depends on foreign investment, particularly from Singapore. For years, the Batam, Bintan and Karimun (BBK) region’s economic growth has been driven by its close connectivity with Singapore.

President Jokowi has now sent the Minister of Investment and Head of the Investment Coordinating Board (BKPM) Bahlil Lahadalia to conduct a dialogue with the community and reach an agreement.

The future success of the National Eco-City Strategic Project ultimately depends on whether the central and regional governments can effectively communicate with and provide adequate compensation for the affected residents of Rempang.

If a non-repressive approach and fair compensation, including permanent housing and jobs for the affected communities can be taken, the project is more likely to get public support and restore the government’s reputation.

Ady Muzwardi is Coordinator of the Center for Southeast Asian Studies and Border Area Management, and Analyst and Lecturer in Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji, Tanjung Pinang, Indonesia.

Siwage Dharma Negara is Senior Fellow and Co-coordinator of the Indonesia Studies Programme, and the Coordinator of the APEC Study Centre, ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute.

This article was first published in Fulcrum, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute’s blogsite.