Sowing the impossible

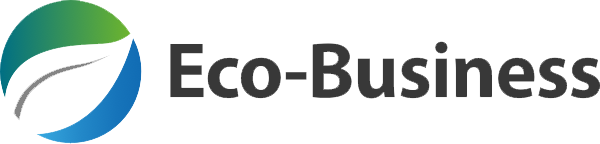

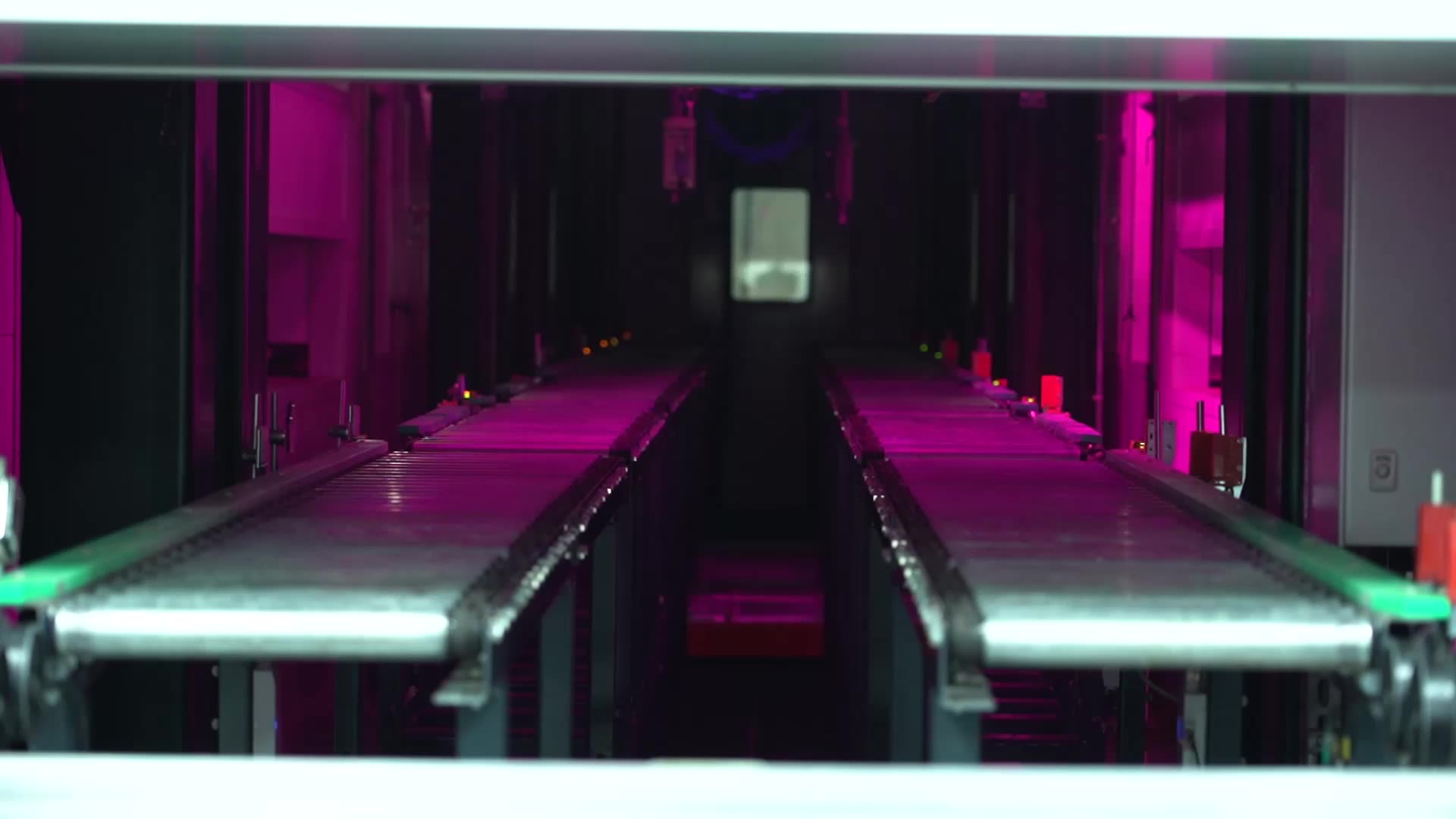

In a high-ceilinged warehouse about a kilometre away from Singapore’s airport, what is set to become the island’s largest indoor vegetable farm is quietly ramping up its production.

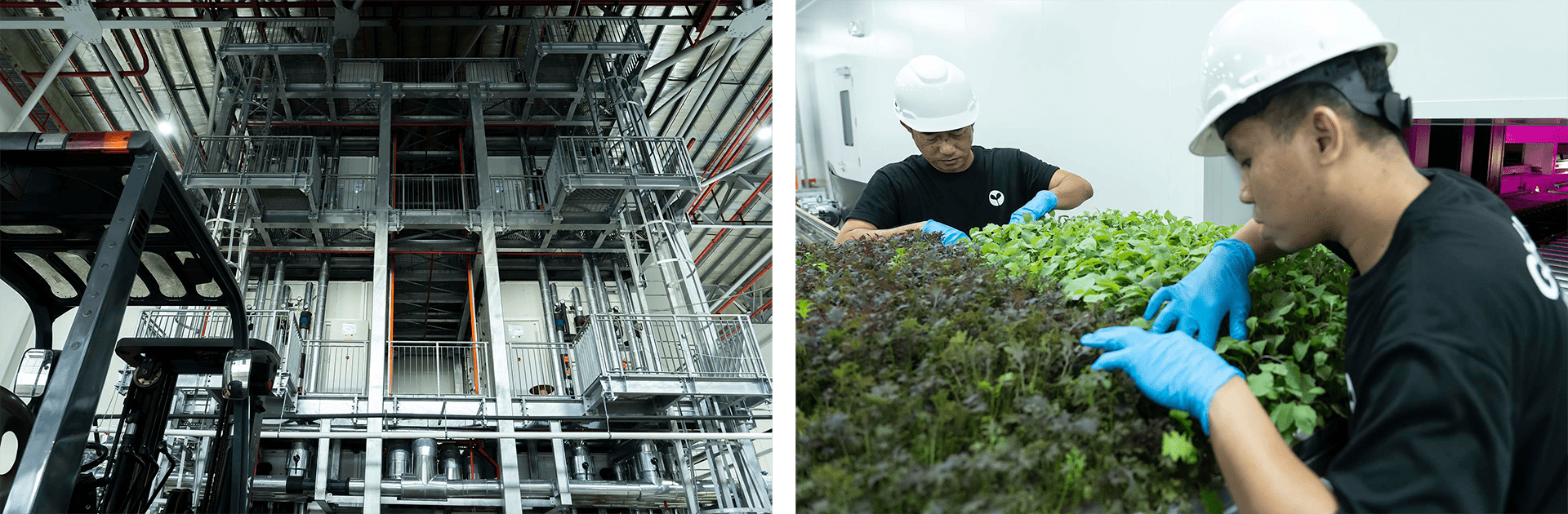

Covid-19, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and export curbs of key food commodities such as Indonesian palm oil and Indian rice in recent years have made food security a worldwide concern.

While Singapore has weathered these impacts better than many countries, food price inflation has been weighing heavily on poorer communities in the city-state. The crises called into question Singapore’s heavy reliance on imports, as globally diversified as they may be. Local production, without the need for lengthy transport and storage, could also mean less carbon emissions.

But realising the vision of becoming more self-reliant for food remains a huge challenge. Land prices in the city-state are infamously high, while neither water nor electricity is subsidised – to the detriment of power-hungry indoor farms as power prices climbed through the roof in recent years.

Word among the agriculture community is that few establishments have been able to reach business profitability.

“Farmers are really struggling,” said Veera Sekaran, professor in practice at the National University of Singapore, pointing to weak market penetration even for old-timers in the scene. Veera had founded VertiVegies, which is involved in local research, and also runs Greenology, a local horticulture consultancy.

“Many of my friends are telling me, ‘I regret, I regret, I regret’,” Veera added, on the sentiments of the industry.

There is an increasing focus now on getting the basics right first. Dr Koh Poh Koon, senior minister of state for sustainability and the environment, told local Chinese daily Lianhe Zaobao last month that it was more important to lay good foundations for the industry than just to focus on reaching production goals. There could be a review of the “30 by 30” target in the coming years, Koh said.

This special report teases the nuances in Singapore's food challenge, from its current growing pains to where it is heading. We examine the city-state's innovation-led agricultural policy, its attempt to set up farming hubs, and the latest efforts to find a breakthrough formula for food self-sufficiency.

Eco-Business is dedicated to reporting on Asia's most important sustainable development issues. We believe in the power of independent journalism and strive to expand the breadth and depth of our coverage with special reports like this. If you like the story and would like to show your support, do consider signing up for our paid subscription to become a member of the EB Circle community.