Can Asia's climate-cooked cities beat the heat?

As global temperatures rise, concrete jungles are packing the heat and putting the lives of urban dwellers at risk. How are Asia's metropolises coping with hotter weather?

With less than a year to go to the 2020 Olympics, Tokyo is coating close to 100 kilometres of road with cooling material and feeding weather data to athletes to help beat the scorching heat that typically descends on Tokyo from July to August.

The sports weather team at Weathernews, a large private weather service company in Japan, spent this summer collecting weather forecast and strategic data to prepare both participants and spectators for the heated games.

By equipping them with information on where the air is cooler, or which areas provide most shade, Japanese sport bodies are hoping their own athletes will be able to one up competitors in the extreme heat.

Tokyo is preparing for extreme heat during the Olympics next year by collecting weather data. Image: Weathernews

Tokyo is preparing for extreme heat during the Olympics next year by collecting weather data. Image: Weathernews

On a very hot day, the human body’s outer and inner temperature rises, affecting overall health. For athletes, prolonged exposure to heat directly influences how they perform, says Koji Horiuchi, a consulting meteorologist on the sports weather team.

Other than for sporting purposes, however, Horiuchi says urban weather is being closely watched by meteorologists as the climate gets hotter and more unpredictable in Japan.

This year, after an unusually long rainy spell, Japan experienced a deadly heatwave in July that claimed 11 lives and landed 5000 people in hospital for heat exhaustion. In response to the erratic weather, the country’s Ministry of the Environment said that if countermeasures were not taken against global warming, such extreme heat conditions will become the norm.

Around the world, scientists are sounding the same warning. The likelihood of extreme heat events is predicted to double and get more intense by 2050 with climate change.

Across Asia, record-breaking temperatures have led to thousands of heat-related deaths and illnesses over the last few years. Invisible but deadly, heat often strikes the most vulnerable communities who lack access to healthcare, air-conditioning and other forms of cooling. The poor, sick and elderly in Asia will typically be the ones who bear the brunt of heat.

People living in subdivided flats and cage homes in Hong Kong for example, experienced indoor temperatures up to five degrees higher than outdoors during a heatwave in May, according to a local non-profit.

Heat is also particularly stifling in dense urban areas, where heat and air pollution mingle to form a toxic brew. It is predicted that the worsening of urban heat will lead to a global healthcare crisis that will cost cities billions worldwide.

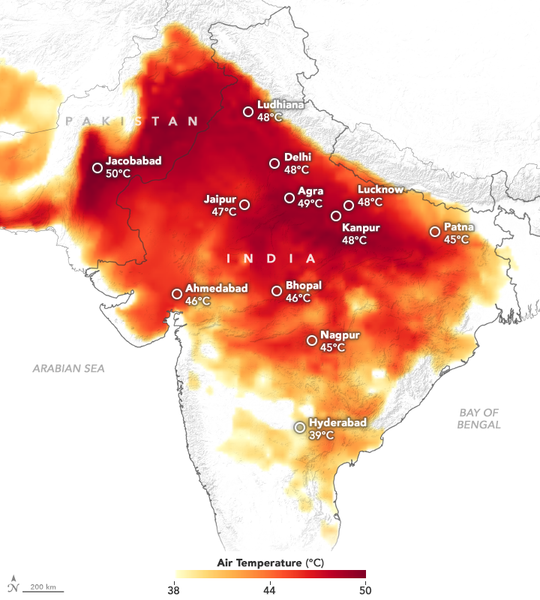

Image: NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens, using GEOS-5 data from the Global Modeling and Assimilation Office at NASA GSFC.

Image: NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens, using GEOS-5 data from the Global Modeling and Assimilation Office at NASA GSFC.

The World Bank further estimates that hotter temperatures turn more than half of the South Asian region into vulnerable "climate hotspots" where standards of living will severely decline.

“Global warming has put my coastal hometown and city of residence of Chennai on simmer,” said Raakhee Suryaprakash, an analyst and writer at Climate Tracker. “Every day, not just in summer, it's becoming progressively hotter here. The sad thing is that the heat does not end in May, it's still hot even in August."

Islands in the sun

Why are cities so hot? In a special podcast with Asia's climate experts, Eco-Business finds out.

Eco-business interview with climate experts Winston Chow and Anjali Jaiswal.

Eco-business interview with climate experts Winston Chow and Anjali Jaiswal.

As global temperatures rise, urban dwellers will be the first to feel the heat. Due to a phenomenon called the urban heat island effect, cities heat up faster than their surrounding areas, which benefit from natural cooling such as vegetation. More rural areas are therefore likely to be much cooler than urban centres.

The way cities are built and run exacerbates hot temperatures that are often most oppressive during the summer. Anyone living in a city will be familiar with the towers of concrete and glass, roads glistening with black asphalt, vehicles emitting plumes of smoky heat and air-conditioning exhausts blasting heat onto the streets below.

Because of this, the weather has already become hotter in Singapore. The past ten years have been the warmest decade on record, with a long term average temperature of 27.9 degrees Celsius in 2018 – 0.4 degrees Celcius higher than the decade before.

The heat island effect is most apparent at night, when the temperature difference between a forested area such as Bukit Timah and the built-up Orchard Road district could be six or seven degrees – a very significant difference, Winston Chow, a professor at Singapore Management University, told Eco-Business.

Chow, who is also a lead author in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s sixth assessment report, said: “In the case of Singapore, the country used to have tropical rainforests and coastal mangroves before 1965. But once we replaced all that with concrete, asphalt and glass surfaces, these materials trap in a lot of heat. They store it during the daytime and then at night they release it.”

Hemalatha, a mother living in Chennai who works at a milk kiosk run by Aavin, a Tamil Nadu-based co-operative, said: “Concrete homes are not suited to cities with extreme temperatures as they allow the outside temperature inside. More insulated homes like wooden homes are better suited for Chennai.”

She added that traditional homes in her neighbourhood used to be made of a mix of limestone, mud plaster and material from coconuts, which provide greater insulation to heat. According to her, these houses are cooler indoors even without a fan or air conditioning.

However, with modernisation, it will be hard to return to using these materials for buildings, she said.

Across Asia, where the modern built environment provides little relief from heat, a typical response to a sweltering afternoon might be to blast the air-conditioner. However, air-conditioning units also eject heat, making the streets outside hotter while cooling the indoors.

Huge energy guzzlers, air-conditioning contributes directly to climate change when powered by non-renewable sources of energy.

“In cities, you have a lot of cars, trucks and buildings with air conditioning and this is a big problem in Asia. You've got that double whammy of using air conditioning as a way of dealing with the increased heat. You ironically make the heat issue worse both for the heat island effect and for climate change,” said Chow.

Are you feeling the heat?

With heatwaves expected to become more common and intense due to climate change, more people around the world will be affected by deadly temperatures.

From Tokyo to Karachi, how are people coping as extreme heat descends on their city? With burgeoning cities providing little respite from sizzling temperatures, which segments of the city population are most at risk from the impacts of heat?

People from across the region tell us how heat is affecting their community and livelihoods.

Koji Horiuchi, sports metereologist, Tokyo:

We have had many more hot nights, and also sudden showers in the Tokyo area. During these hotter, tropical nights, the temperature does not fall below 25 degrees Celsius.

On a hot day, our body temperatures rise, making it hard for athletes to maintain their normal performance. Weather forecast data can help those training for the Olympics come up with competition strategies and counter measures to the heat during the Games.

Victor Latican, jeepney driver, Manila:

Sometimes it’s so hot, and sometimes, it suddenly just rains. If it’s too hot then we just rest in the shade but if it rains too hard then we don’t have many passengers. Where I live, we open the windows or use electric fans, but it’s still too hot.

Photo by Michu Đăng Quang on Unsplash

Photo by Michu Đăng Quang on Unsplash

Raakhee Suryaprakash, copy editor, Chennai:

Every day, not just in summer, it's becoming progressively hotter. My home has two air conditioners, one in the front and master rooms. This summer, I worked from home from night to sunrise. When the heat and humidity got to me, I would move to the front room. As a result, the summer electricity bill has been double the usual amount.

Hemalatha, assistant worker at an outdoor milk kiosk, Chennai:

It’s hard to work in the metal box booth in the heat. We work in shifts of 2 hours each as one person cannot stay in the booth for too long. The heat affects from the ground up – heating the legs. Taking a break at home is the only way to beat the heat at its peak.

The temperature eclipses 40 degrees Celsius here but many people still have to work outside.

Hemalatha works at an outdoor milk kiosk, assisting her husband who is staff at Aavin, a Tamil-Nadu based milk producer's union.

Hemalatha works at an outdoor milk kiosk, assisting her husband who is staff at Aavin, a Tamil-Nadu based milk producer's union.

Celia Wan, real estate consultant, Beijing:

My job requires me to be outside a lot, especially during summertime. This year, summer came earlier and it's noticeably hotter than before. In the past, the weather would cool down after sunset but now the nights are even warmer and more stifling than daytime.

Rudi, mobile street food hawker, Jakarta:

I spend my day in the street. When it’s so hot, I feel my ears and hands burn. The heat in the past and nowadays is different. The heat didn’t sting too much before.

I live in a rented room, with a roof made of cement. Even though I use a fan, it’s still hot. Sometimes, I choose to sleep on my ceramic floor.

Nadeem Ahmad, head of policy and advocacy, WaterAid Pakistan:

Women typically stay at home to take care of children and do housework. Restrictions arising from fixed gender roles make it harder for them to escape the heat, which often leads to health complications.

Heat also causes food to turn bad faster. This often leads to nutrition deficiency, which tends to affect women and children the most.

Women and children are most vulnerable to the impacts of heat. Image: Natural Resources Defense Council

Women and children are most vulnerable to the impacts of heat. Image: Natural Resources Defense Council

Where heat hits hardest

As extreme heat encroaches upon the city, not everyone will suffer equally.

Those who have air conditioning or live close to green spaces have the privilege of keeping cool, while people who work outdoors or have little access to cooling technologies suffer the most.

Rudi, a mobile food hawker who lives in a rented room and roams the streets of Jakarta selling meatballs soup, said that the government “does not care about unfortunate people like him” and that the problem of heat became worse because the authorities cut all the trees by the road.

“I spend my day in the street. When it’s so hot, I feel my ears and hands burn. It used to be easy to take shelter under the tree, or in a community hall. I can’t find those now,” he said.

He added that even with a fan, it would get so hot in his room that he would choose to sleep on the ceramic floor.

When he was doing his PhD in Phoenix in the United States, Chow found that lower income areas were more vulnerable to extreme heat and therefore disproportionately affected by both heatwaves and the urban heat island.

“If you are well-off, if you have access to resources like air conditioning, if you have a certain level of income that allows your home to have green spaces such as backyards with grass or trees, you will be better off,” said Chow. “You don't have to expose yourself to a high level of heat stress that some places have.”

Regina Vetter, network manager of the Cool Cities Network at C40 Cities, a global platform for cities to share knowledge on climate change, agreed: “In many low-income areas, there might be less green space or parks where people can go to cool off. It's a big inequality issue.”

According to a report by C40 cities titled “The future we don’t want” if greenhouse gas emissions remain unchecked, 215 million of the urban poor in 500 cities in developing countries will be exposed to average summertime highs of over 35 degrees Celsius.

This temperature is commonly referred to as a wet-bulb temperature, at which the human body is no longer able to cool itself and begins to overheat.

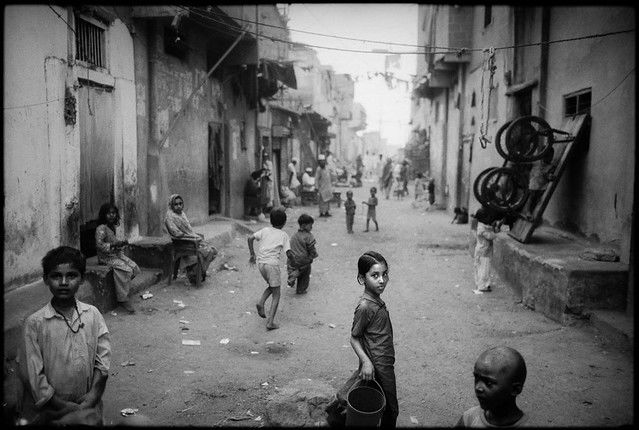

A slum in Karachi's Machar Colony, Pakistan. The urban poor are most vulnerable to the impacts of extreme heat. Image: Balasz Gardi/Flickr

A slum in Karachi's Machar Colony, Pakistan. The urban poor are most vulnerable to the impacts of extreme heat. Image: Balasz Gardi/Flickr

“The poor are the most vulnerable and among them the old, infirm, women and children as they lack the ability to safeguard themselves against extreme heat,” said Afia Salam, a journalist and philanthropist from Karachi.

“This is due to their small, poorly ventilated living quarters, lack of access to medical assistance, and lack of mobility to move to where there is respite from intense heat.”

Four years ago in Karachi, morgues ran out of space and had to reject corpses when a deadly heatwave gripped the city and left over 1,200 people dead.

“When morgues are closing their doors because of the extreme heat, you know it's a public health crisis. These are big wake up calls to civil society, city leaders and national governments,” said Anjali Jaiswal, founding director of the India Climate and Energy Program at the National Resource Defence Council (NRDC), a United States-based environmental advocacy group.

Taking a chill pill

How are city dwellers coping with the heat?

In India, people are adapting to the heat by changing their diets, avoiding spicy food and sticking to fish and water-rich vegetables that do not add heat to the body.

On the country’s south eastern coast in Chennai, Hemalatha has more than one way to keep cool. Water is kept chilled in a mud pot, to which she adds the root of the vetiver plant known to help reduce body temperature.

At home, she puts a wet blanket on the windows to cool the air and wipes the floor with water before the family lies down for the night.

Taking a break from the heat, a man drinks from a roadside stall. In India, people are drinking more buttermilk to keep cool. Image: Eco-Business

Taking a break from the heat, a man drinks from a roadside stall. In India, people are drinking more buttermilk to keep cool. Image: Eco-Business

Elsewhere in the city, those with flexible work arrangements escape the peak of summer by taking afternoons off or move to higher ground, vacationing at hill stations where the climate is colder.

Rakhee said that she worked from home at night this summer, although her electricity bills doubled because of air-conditioning.

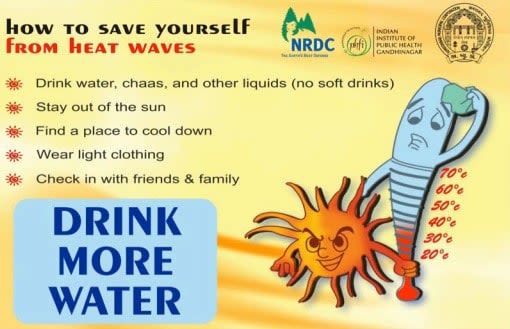

Heat advisory poster from the Ahmedabad Heat Action Plan in 2016. Image: Natural Resources Defense Council

Heat advisory poster from the Ahmedabad Heat Action Plan in 2016. Image: Natural Resources Defense Council

However, she noticed that the government health departments have started launching summer survival guides and heat advisories that recommend people not to go out in the afternoons and to wear light cotton clothing.

“This was never formal practice two summers ago,” she said.

Siti Kumari, a research officer who has lived in the cities of Delhi, Gujarat and Chennai, also said that weather and health advisories are increasingly being broadcast on television in various cities. People are also tailoring their work hours to the climate, staying indoors when the sun is at its peak.

Heat-proofing the city

As urban dwellers brace themselves for warmer weather, how are cities cooling down?

In Singapore, Chow and his team from Cooling Singapore, a research initiative focused on urban heat, have come up with over 80 strategies to protect city dwellers from warmer weather.

Ranging from electric vehicles and green walls to water catchment areas and cool roofs, the solutions serve to make built spaces cooler and more efficient, while not putting further pressure on the environment.

In other cities such as New York and Abu Dhabi, innovative measures such as automated facades and smart-tinting glass that provide shade or let light in according to outdoor temperatures, and green roads that allow water to seep in are also being tested and implemented to limit people’s exposure to heat.

Qatar, the host of the 2022 FIFA World Cup, is working with a Japanese partner to cool pavements using a heat-reflective pigment. Image: Twitter/Ashghal

Qatar, the host of the 2022 FIFA World Cup, is working with a Japanese partner to cool pavements using a heat-reflective pigment. Image: Twitter/Ashghal

However, of the numerous measures, Chow believes that greening the city, from small strips of roadside trees to rooftop gardens is the most effective and cost-friendly way of dealing with the heat, given that the greenery can be distributed across all residential, commercial and industrial areas.

“Green spaces are tremendous solutions that reduce the heat island simply because they behave like forests,” he said. “There’s a lot of evaporation and plant transpiration that occurs to help reduce the radiant heat that you feel during heatwaves."

Chow also pointed to low cost heat action plans that were first introduced in the city of Ahmedabad after a murderous heatwave in 2010. Heat action plans have since been implemented in over 100 cities in India, and comprise of three main elements: an early warning system, community outreach and capacity building.

“The early warning systems are key to saving lives. They notify the medical officers and all the major emergency departments so everyone can get ready to respond to the heat,” said Jaiswal, who worked closely with local partners and the city government in Ahmedabad to build the city's resilience to heat.

The Ahmedabad Municipal Corportation sends out warnings based on a simple colour-coded ‘heat alert’ system. Image: Natural Resources Defense Council

The Ahmedabad Municipal Corportation sends out warnings based on a simple colour-coded ‘heat alert’ system. Image: Natural Resources Defense Council

She added that community outreach and communication are key to spreading awareness of protective measures against heat, especially in vulnerable communities. In slum areas with no access to air conditioning, things like water stations at temples and in public spaces, as well as longer opening hours in public parks, go a long way in helping people cope with extreme heat.

However, Raakhee is worried that “unplanned and unsustainable city growth” will cause her city to become “unlivable” in the future, especially as severe water shortages will make the hot climate unbearable.

“What is really worrying is that construction still continues rampantly, trees are cut, lakes are filled up and wetlands reclaimed to create more land for the growing greater metropolitan area and an exploding population,” she said. “I hope the local state and national government implements policies to increase urban tree cover and water body restoration in megacities like Chennai."

Chow believes that cities worldwide have to continue looking for solutions that address both the heat island and climate change, ultimately moving towards cleaner sources of energy to combat the worst impacts of warming.

“On a large scale, there has to be a global push towards using energy sources that are renewable. Personally, I don’t think that this transition is happening quickly enough.”