The nuclear industry is celebrating breaking records that have stood for a quarter of a century − but a new update on its successes still fails to disperse the clouds over its future.

Ten new nuclear reactors came on line last year worldwide, and more new reactors are being built than at any time since 1990. According to the report by the World Nuclear Association (WNA), there were 66 power reactors under construction across the world last year, and another 158 planned. Of those being built, 24 were in mainland China.

In what it promises will be an annual update of the industry’s “progress”, the WNA presents a rosy picture of the future of the industry, which it hopes will produce ever-increasing amounts of the world’s power.

Currently, the industry provides 10 per cent of the world’s electricity, but its target is to supply 25 per cent by 2050 − requiring a massive new build programme. The plan is to open 10 new reactors a year until 2020, another 25 a year to 2030, and more than 30 a year until 2050.

Vast increase

The industry regards this as vital to ensure that the governments of the world keep to their plan of keeping the planet from passing the internationally-agreed limit of a 2°C rise in temperatures above pre-industrial levels. It says only a vast increase in new nuclear power, combined with renewables, can achieve this.

“The World Nuclear Association’s vision for the future global electricity system consists of a diverse mix of low-carbon technologies – where renewables, nuclear and a greatly reduced level of fossil fuels (preferably with carbon capture and storage) work together in harmony to ensure a reliable, affordable and clean energy supply,” the report says.

Despite its optimism, the WNA admits that the situation globally for the industry is “challenging”, particularly in Europe and the US, where low electricity prices are making nuclear power uneconomic.

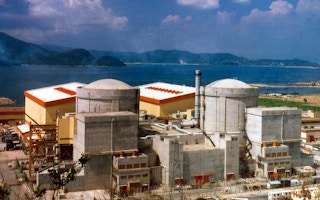

The brightest prospect is China, where nuclear power is shielded from market forces. Eight new reactors were connected to the grid in 2015, with many more scheduled for construction as part of China’s bid to phase out coal and improve air quality.

The largest nuclear power exporter is Russia, and President Putin is offering countries generous terms, including providing the fuel for the reactors and then taking the waste back to Russia.

This plan, which ties countries into close partnerships with Russia, could be seen to pose political dangers for the countries concerned, giving Russia direct control over their energy supplies.

Many countries have chosen to ignore this potential problem. As a result, Russia’s national nuclear industry is currently committed to building new reactors in China, Hungary, India and Turkey, and is engaged with potential buyers in Jordan, Kazakhstan, Nigeria, South Africa and Vietnam, among others.

South Korea and India are also quoted in the WNA report as boosting nuclear power with new commitments in 2015.

In Europe and North America, however, nuclear operators are struggling. In Europe, this is mainly because of political opposition in Germany and the fact that the French nuclear industry’s flagship new design, currently under construction, is badly delayed by cost overruns and time delays.

Hard to compete

The recent UK vote to leave the European Union, which took place after the WNA report was compiled, will make this situation worse. The British plan to build 10 new reactors, including four of French design, now seems much less likely to be realised.

In North America, the success of the shale gas industry has meant that nuclear power finds it hard to compete on price.

Aside from new build, there is great emphasis in the report on the continued operation of nuclear power stations well beyond their original design life. It says that, in many cases, there is no reason why, with regular refurbishment, many nuclear reactors could not continue in service permanently. In many cases, it says, it would be cheaper to refurbish an existing station than to build a new one.

The exception is the advanced gas cooled reactors operated in the UK. These have life-limiting factors that mean they will close well before the 60-year lifespan that reactors of other designs could easily manage, the report says.

This story was published with permission from Climate News Network.