Seeing mangroves regrow

Documenting the surprise resurgence of Iloilo's coastal forests

26 July 2024

On International Day for the Conservation of the Mangrove Ecosystem, Eco-Business looks at the unexpected rapid growth of a thriving mangrove forest in Iloilo City, Philippines, following the completion of a man-made floodway. The archipelagic state has a high rate of mangrove deforestation due to coastal development.

In coastal Iloilo City in central Philippines, the completion of a man-made floodway has unexpectedly sowed the seeds for the rapid growth of a thriving mangrove forest – on the fringes of one of the fastest-rising urban centres in the country.

The Philippines loses nearly one per cent of its 311,400 mangrove cover annually, with the archipelago being among the top 10 countries with the highest mangrove deforestation rates in the world. Much of this loss is attributed to widescale coastal development and the proliferation of fish farms for aquaculture.

‘Undervalued’ ecosystem

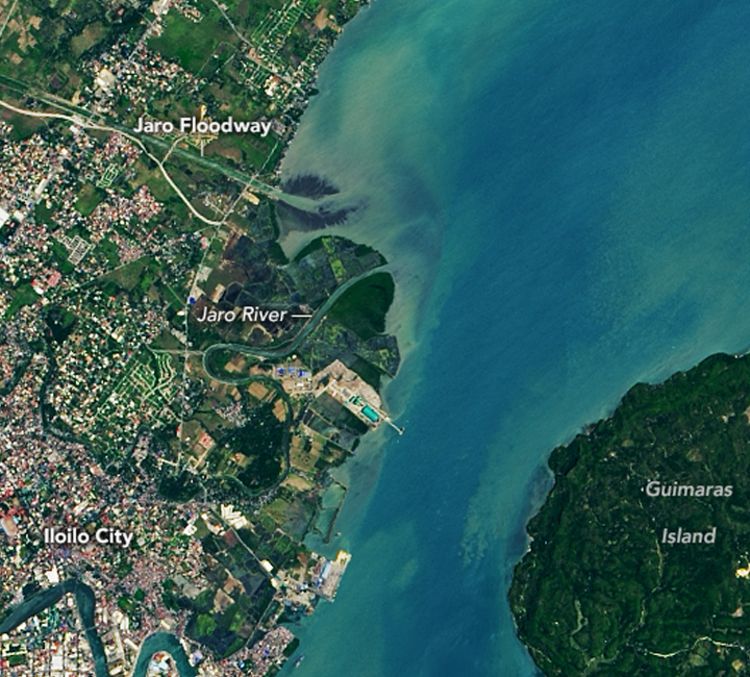

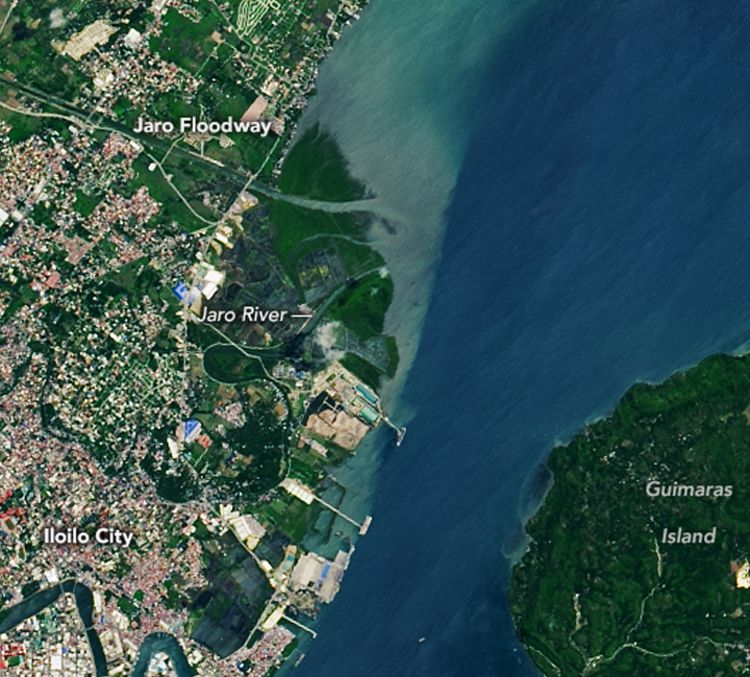

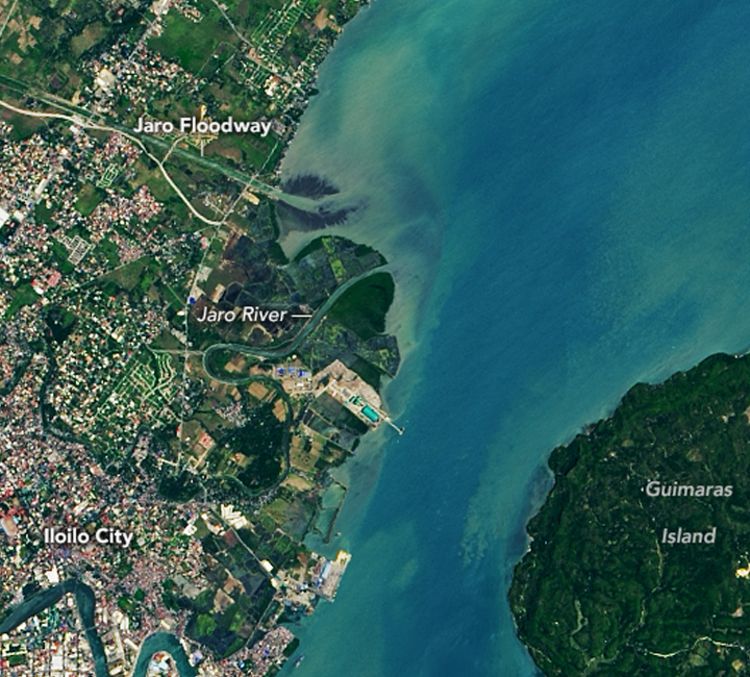

At the mouth of Iloilo’s Jaro Floodway, a mangrove forest is growing at an unprecedented rate of more than four hectares a year, with the exposed coastline enabling the flourishing of several endemic mangrove species. Diverting Iloilo’s Aganan and Tigum rivers directly into the Iloilo Strait, the floodway was completed in 2012 to help mitigate flooding brought about by annual torrential rains.

The waterways of Iloilo City – although one of the Philippines’ highly urbanised hubs – are home to 25 endemic mangrove species. The city’s namesake Iloilo River hosts the densest urban mangrove ecosystem in the country after years-long rehabilitation efforts.

Mangrove mapping will be an effective decision-making tool for us to consider the true cost and the negative impacts of the [development] projects on our environment.

Research led by Dr Resurreccion Sadaba, lecturer at the University of the Philippines Visayas, mapped some 132 hectares of mangrove forests along Iloilo City’s coastal and river systems.

Satellite imagery shows the rapid growth of coastal vegetation at the mouth of the floodway between 2014 and 2021. Image: NASA Earth Observatory

Satellite imagery shows the rapid growth of coastal vegetation at the mouth of the floodway between 2014 and 2021. Image: NASA Earth Observatory

Satellite imagery shows the rapid growth of coastal vegetation at the mouth of the floodway between 2014 and 2021. Image: NASA Earth Observatory

Satellite imagery shows the rapid growth of coastal vegetation at the mouth of the floodway between 2014 and 2021. Image: NASA Earth Observatory

Satellite imagery shows the rapid growth of coastal vegetation at the mouth of the floodway between 2014 and 2021. Image: NASA Earth Observatory

Satellite imagery shows the rapid growth of coastal vegetation at the mouth of the floodway between 2014 and 2021. Image: NASA Earth Observatory

Satellite imagery shows the rapid growth of coastal vegetation at the mouth of the floodway between 2014 and 2021. Image: NASA Earth Observatory

Satellite imagery shows the rapid growth of coastal vegetation at the mouth of the floodway between 2014 and 2021. Image: NASA Earth Observatory

First steps: nationwide mapping

Mapped using satellite-based optical and radar data, the DENR and PhilSa's nationwide mangrove map indicates coastal mangrove cover in green. Image: DENR

Mapped using satellite-based optical and radar data, the DENR and PhilSa's nationwide mangrove map indicates coastal mangrove cover in green. Image: DENR

A man walks along the Iloilo River Esplanade, a 10-kilometre linear park, in Iloilo City in the Philippines' Western Visayas region.

A man walks along the Iloilo River Esplanade, a 10-kilometre linear park, in Iloilo City in the Philippines' Western Visayas region.

The mangroves have a total sequestration potential of 255,664 metric tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, according to estimates by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). This carbon sink capacity is comparable to removing 54,746 fossil fuel-powered vehicles from the roads for a year or transitioning 8.6 million incandescent lamps to energy-efficient LED (light-emitting diode) bulbs. Mangrove forests can store up to four times as much carbon as other tropical ecosystems.

Sadaba notes that mangrove forests play a crucial role in supporting the local ecosystem, as well as provide several benefits to coastal and river communities.

“Mangroves serve as nurseries and habitats for many fish and marine species, contributing to the abundance and diversity of marine life. They also act as natural buffers, protecting the coastline from erosion, storm surges and sea-level rise,” he explained, adding that the hardy species also contribute to water quality improvement and sequestering carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to mitigate climate change.

Despite these ecosystem services, mangroves remain “undervalued”, said Sadaba.

In Southeast Asia, the Philippines is second to Myanmar when it comes to rapid mangrove cover loss.

Using satellite-based optical and radar data, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) and the Philippine Space Agency (PhilSA) developed a nationwide mangrove map in 2023.

The agencies are now working with the academic community and non-governmental organisations to verify the map’s findings through field validation and on-the-ground reporting. At the time of publication, the initiative has reached a third of its goal of verifying at least 30,000 Philippine mangrove sites this year.

Rina Rosales, a sustainable natural resource management specialist affiliated with consulting firm Resources, Environment and Economics Center for Studies (REECS), hopes the mangrove mapping initiative will improve the country’s Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) System. Developers of infrastructure projects in the Philippines are required to evaluate the likely environmental impacts of these projects via EIAs and public consultations.

“Mangroves are among the most affected ecosystems when it comes to urbanisation and development,” said Rosales. Whether it is a coastal reclamation project, or the building of tourism infrastructure along beaches, or even ground-levelling in airport construction, "mangroves are often the first to go" despite strict regulations being in place, she said.

Measuring natural capital

Civic groups have slammed the construction of the New Manila International Airport in Bulacan, a province in the Central Luzon region, for large-scale mangrove deforestation. In Iloilo, the erection of the mega Panay-Guimaras-Negros bridge, estimated to start in the second quarter of 2025 to connect the islands in Western Visayas, could entail the cutting down of up 400,000 mangrove trees.

“Mangrove mapping will be an effective decision-making tool for us to consider the true cost and the negative impacts of the [development] projects on our environment,” Rosales said.

“It could prove important in determining if a project is a ‘go or no-go’ given the degradation it could potentially cause. Or in the most extreme circumstances, it could show how much compensation is needed to offset the destruction. This, of course, should be the last resort.”

Rosales also noted that the mapping programme seems aligned with the administration’s push to put a price tag on the Philippines’ natural resources and natural capital.

It will help natural capital accounting, she said, if the authorities can know the location of the mangroves, their condition and the extent of degradation, while they look into the ecosystem services they need to provide.

To capitalise on the unprecedented mangrove growth along the Jaro Floodway, the local government of Iloilo City plans to establish the Hinactacan Mangrove Eco-Park in the area. The park is envisioned to be part eco-tourism site and part scientific learning centre with the establishment of elevated walkways and gazebos along the coastal area.

Youth-led Mangrove Matters PH, however, reminds that these developments should not go too far such as they alter nature.

“Although the city authorities are taking some significant steps to consider nature in urban planning, there is still a long way for Iloilo to be a true champion in conservation,” said Mangrove Matters PH founder Matthew Vincent Tabilog, who pointed out that the expansion of the city’s river esplanade parks might entail chopping down old mangrove growths.

Tabilog also brought attention to the “inherent spatial [in]justice” of the park projects as the efforts to build these facilities seemingly will cater to affluent communities in [the city’s] business districts and benefit condominium developers”.

An instruction video in Tagalog from the DENR for its research partners on how to conduct verification against its nationwide mangrove map.

The carbon sink potential of Iloilo City's mangrove forests is comparable to removing 54,746 fossil fuel-powered vehicles from the roads for a year.

The carbon sink potential of Iloilo City's mangrove forests is comparable to removing 54,746 fossil fuel-powered vehicles from the roads for a year.

Iloilo City's environment office is working to cancel fishpond lease agreements of abandoned fish farms and saltbeds around the city to potentially open up 250 more hectares for mangrove restoration.

Iloilo City's environment office is working to cancel fishpond lease agreements of abandoned fish farms and saltbeds around the city to potentially open up 250 more hectares for mangrove restoration.

Iloilo City's environment office is working to cancel fishpond lease agreements of abandoned fish farms and saltbeds around the city to potentially open up 250 more hectares for mangrove restoration.

Iloilo City's environment office is working to cancel fishpond lease agreements of abandoned fish farms and saltbeds around the city to potentially open up 250 more hectares for mangrove restoration.

Iloilo City's environment office is working to cancel fishpond lease agreements of abandoned fish farms and saltbeds around the city to potentially open up 250 more hectares for mangrove restoration.

Iloilo City's environment office is working to cancel fishpond lease agreements of abandoned fish farms and saltbeds around the city to potentially open up 250 more hectares for mangrove restoration.

Tackling the biodiversity and climate twin crises

For many of the country's coastal communities, mangrove conservation is a very personal issue. This is especially as there are anecdotal evidence of these precious coastal forests protecting them from the devastation of super typhoons, said Tabilog.

In Barangay Sampinit in Negros Occidental’s Bago City, for example, members of the community have shared about how the mangroves protected them from super typhoon Odette. In Balaring in Silay City, the barangay [village in Tagalog] used to be frequently flooded but the community decided to plant more mangroves as a way to reduce the impacts of coastal flooding, recounted Tabilog.

According to Engr Neil Ravena, head of the Iloilo City Environment and Natural Resources Office, the local government is working with DENR and Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) to cancel fishpond lease agreements of abandoned fish farms and saltbeds around the city to potentially open up 250 more hectares for mangrove restoration.

In a recent paper published ahead of the United Nations Biodiversity Conference later this year, Nathalie Pettorelli of the Zoological Society of London highlighted the inherent intersection between climate change and biodiversity loss.

Noting that “world leaders [need to put] nature at the heart of their decision-making,” she cited the proper implementation of nature-based solutions such as mangrove restoration as one of the most effective ways to tackle the intertwined biodiversity and climate crises simultaneously. Much of the Zoological Society of London’s ongoing mangrove restoration programmes are focused on the Philippines.

“Functioning ecosystems aren’t just important for addressing rapid climate change – losing them impacts every aspect of our lives, from food security to access to clean water. We need these ecosystems to be recognised and conservation to receive the resources needed for it to be part of the solution towards tackling climate change and championing human wellbeing,” Pettorelli concluded.

In May, conservation organisation International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) warned that, without significant changes, more than half of the world’s mangrove ecosystems will be at risk of collapse by 2050.

Want more Philippines ESG and sustainability news and views? Subscribe to our Eco-Business Philippines newsletter here.