Sustainable finance in Asia: Taxonomies

How can taxonomies help accelerate green finance in Asia?

Introduction

In recent years, Asia’s economic development has been spurred by government and private sector action in sustainable development. With COP26 in Glasgow paving the way for stronger leadership to mobilise capital for the net zero transition, 2022’s G20 summit is widely expected to lay the roadmap for greater alignment of the financial markets.

Asia’s sustainable economy – set to reach US$5 trillion by 2030, according to McKinsey – is a wealth of opportunity. But that value requires assurance by governments and financial markets that sustainability is more than a label, or just a concept.

Enter taxonomies – a tool that can translate commitments into action.

A sustainable finance taxonomy assesses the contribution from different parts of the economy to sustainability goals. These frameworks provide criteria, at different levels of granularity, that activities, assets and products must meet to qualify as sustainable.

This clarity brings extra rigour and credibility to ESG claims as well as sustainability goals.

Globally, national and regional taxonomies for sustainable finance are relatively new but fast-changing.

How is the landscape for taxonomies unfolding in Asia? And what can improve the usability of these systems to help Asian economies on the path to climate resilience?

This report – compiled through research and engagement with policy observers and practitioners – aims to provide a clearer picture of taxonomies in Asia, including the local nuances that are influencing new ideas and development, with an eye on the road ahead.

Photo by Nicholas Doherty on Unsplash

A snapshot of Asia's taxonomies

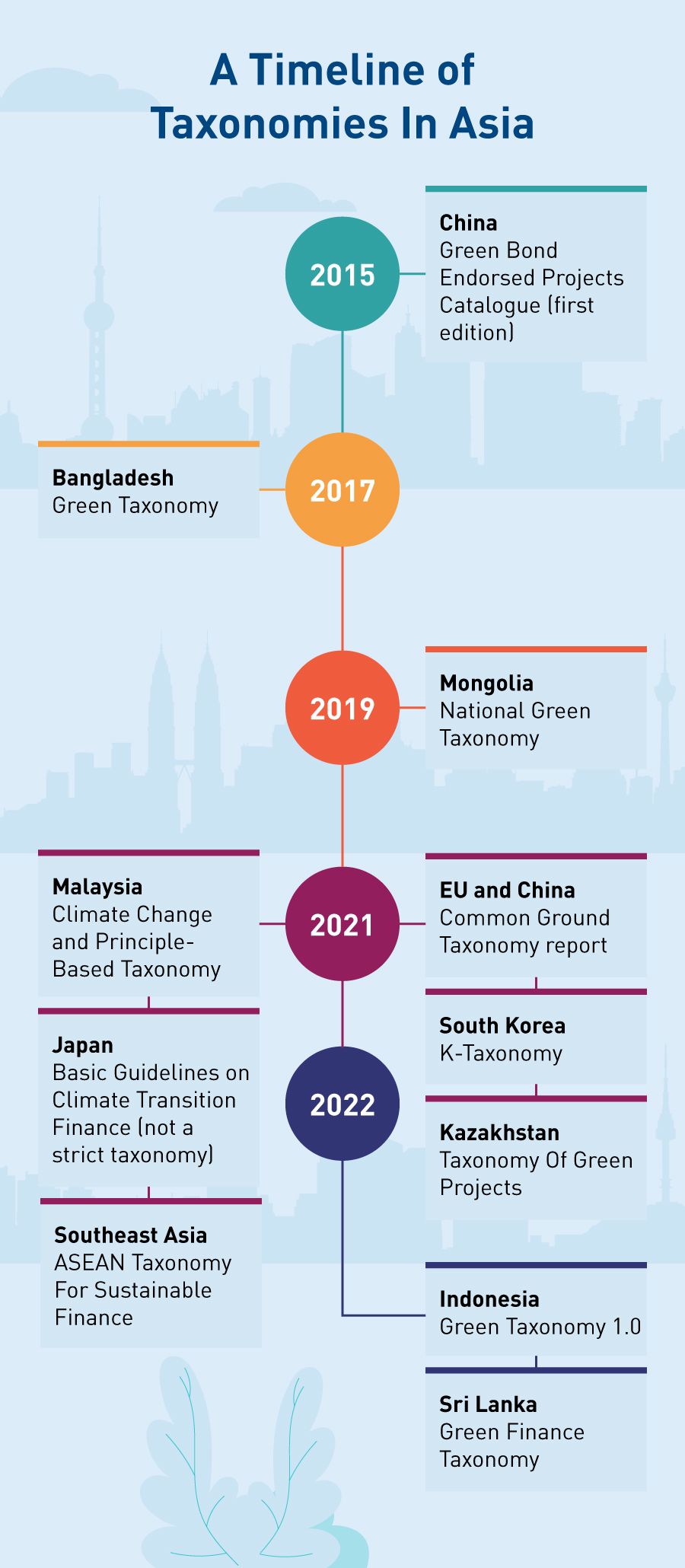

China, Bangladesh and Mongolia were among the first countries in Asia to publish green taxonomies, releasing their first lists of eligible products and activities between 2015 and 2019.

Since then, five more Asian countries – Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, South Korea and Sri Lanka – have unveiled their own definitions and frameworks.

More taxonomies are on the way, especially in developing markets in the region tapping on green opportunities in the region's energy transition.

A region-wide taxonomy for ASEAN launched in November 2021 to align development in Southeast Asia, where the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam are also working on their first national versions.

South Asian markets are staking their claims too. India and Pakistan are also working on their own taxonomies, following Bangladesh and Sri Lanka.

Figure 1: A timeline of taxonomies in Asia. Infographic: Eco-Business/Philip Amiote

Figure 1: A timeline of taxonomies in Asia. Infographic: Eco-Business/Philip Amiote

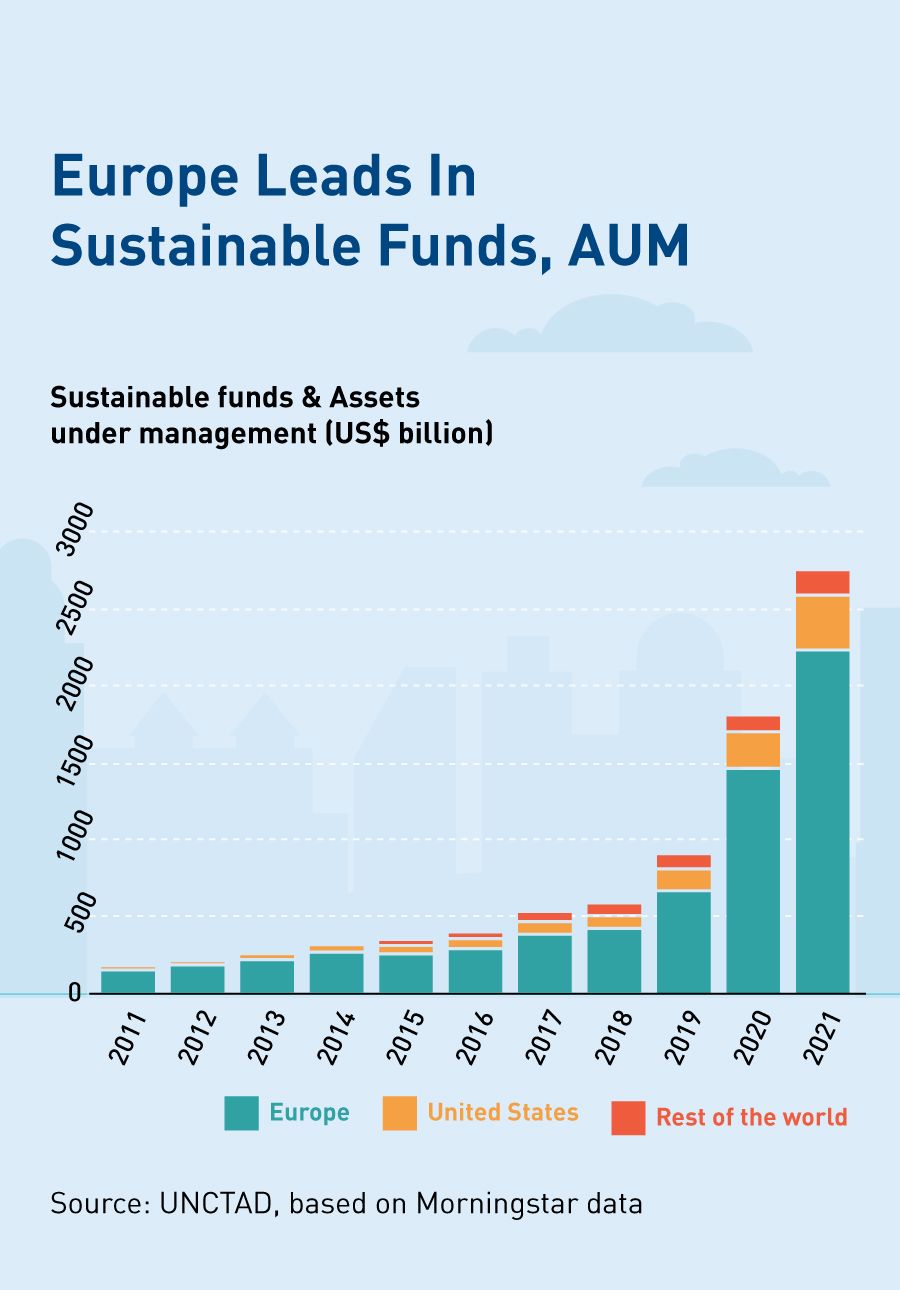

Figure 2: Europe leads in sustainable funds by AUM. Infographic: Eco-Business/Philip Amiote

Figure 2: Europe leads in sustainable funds by AUM. Infographic: Eco-Business/Philip Amiote

An influential force: The role of the EU Taxonomy

One factor speeding up the development of local taxonomies is the release of a wide-ranging framework from the EU in 2020, which is seen as the most comprehensive taxonomy for sustainable finance to date.

As the EU is a global leader in green finance, many countries are keeping a close watch on the bloc for industry best practices and climate stewardship.

Europe accounted for more than half of the global market for sustainable bonds over the first nine months of 2022, according to Refinitiv, a data provider.

The EU also accounted for over 80% of sustainable funds and assets under management, according to the UN, citing Morningstar data.

At the same time, the EU is a major trading partner and large-scale investor in Asia, further amplifying its influence through supply chains and carbon markets.

As the EU rolled out its wide-ranging taxonomy, banks and policymakers in other parts of the world wanted their say too.

“The sense of urgency to define and shape what is considered sustainable, in the midst of all the climate commitments, has been accelerated by developments in the EU taxonomy,” observes Joanne Khew, director and ESG specialist at Prudential’s asset management arm, Eastspring Investments.

“Asia needed to quickly define what it means for us,” Khew adds. “The EU taxonomy has become the de facto industry guide, but there are a lot of regional nuances that need to be adapted for Asia.”

The EU has strict classifications for green and non-green activities. This can limit funding options for sectors that fail to meet these high standards — including those with the potential to scale up their sustainability practices. More flexible criteria could encourage investment in transition activities that help emerging markets decarbonise.

Ways to build a taxonomy

Different ways to build a taxonomy

Generally, national taxonomies are currently grouped into three different approaches. Countries can mix and match aspects of these approaches to create taxonomies that reflect their national priorities, resources and capabilities.

Detailed metrics provide a clearer link to decarbonisation goals, as well as more authoritative labels for financial products, giving investors more confidence.

These systems are resource-intensive, however. While suited to richer markets, this kind of information might be unavailable or inconsistent elsewhere.

“I wonder if too much time and resources will be consumed for precise thresholds,” muses Joseph Chun, partner at the ESG practice for Singapore-based law firm Shook, Lin & Bok.

“Sometimes, precision does not equate with accuracy,” he adds. “In this regard, a principles-based taxonomy is less precise as it uses qualitative criteria. But it is also faster to introduce and possibly to implement, although potentially uncertain in application.”

Some jurisdictions take a hybrid approach, like ASEAN’s regional taxonomy. A base tier uses a principles-based system, called the Foundation Framework, to keep entry barriers low for markets starting on their taxonomy journey.

For countries ready to take the next step, an upper tier, called the Plus Standard, incorporates more data-centric technical screening. This allows more direct comparisons with other markets using similar criteria, such as the EU.

These two main tiers are further segmented using a traffic light system, creating phased transition targets as well as green goals.

“It makes sense for the national taxonomies to not rush ahead, because you want the national taxonomies and the regional taxonomy to be interoperable,” says Sharon Seah, a senior fellow at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, a Singapore-based think tank.

“You don't want investors to be caught between the two taxonomies and have to make certain hard decisions. You want to make it easy for everyone to understand.”

“It makes sense for the national taxonomies to not rush ahead, because you want the national taxonomies and the regional taxonomy to be interoperable.”

Sharon Seah, Senior Fellow at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, a Singapore-based think tank

Photo by Steven Weeks on Unsplash

Have taxonomies accelerated green finance in Asia?

Over the long term, taxonomies would need to build up greater reach and depth, supporting financial products with different risk profiles across the equity markets as well as the debt markets, to help generate the money Asia needs.

Even in China, a pioneer in green classifications, most sustainable financing still takes place within low-risk products, such as bonds and loans, notes Wenhong Xie, head of China Programme at Climate Bonds Initiative, an international not-for-profit focused on capital mobilisation for climate goals.

Chinese banks use government-approved whitelists to monitor their own lending, following government quotas on support for green projects.

But policies differ by province, while multiple classification systems – varying from one bank to another – are not easy to monitor and verify.

Sustainable finance’s uptake in China largely rests on government mandates so far. For further progress, local banks need to have more meaningful incentives, ideally based on greater alignment between industry and finance. Improved transparency and disclosure can also encourage investors to commit.

“Having a taxonomy alone wouldn't do the trick, partly because the Chinese economy and financial system is quite top-down,” Xie says.

“When there is a taxonomy, everybody will follow, but are they really putting money in?” Xie asks. “A taxonomy provides a very important basic framework and underlying definition, but you need other incentives for asset owners to meaningfully allocate more capital into this space.”

To facilitate more cross-border investment, China is working with the EU on a shared framework, called the Common Ground Taxonomy (CGT). The first version was published in November 2021.

Since then, the CGT has already been cited in four green bonds, collectively raising about US$2.1 billion between them, as well as two green loans totaling about US$275 million, from Chinese banks and institutions. There is little information on use by European lenders, however.

“A taxonomy provides a very important basic framework and underlying definition, but you need other incentives for asset owners to meaningfully allocate more capital into this space.”

Wenhong Xie, Head of China Programme at Climate Bonds Initiative

The Road Ahead

Figure 4: Taxonomy development in Asia Pacific. Infographic: Eco-Business/Philip Amiote

Figure 4: Taxonomy development in Asia Pacific. Infographic: Eco-Business/Philip Amiote

Local context is everything

Across Asia, new taxonomies are undergoing – or will soon experience – their first real tests, as market participants use them for the first time.

National taxonomies must tread a fine line to succeed. If taxonomies are too burdensome, they won't be practical. But if they are too simplistic, they won’t be effective.

Banks and governments must also tread a fine line between local relevance and international compatibility for taxonomies to work well.

Overall, the taxonomy scene in Asia is evolving. A unified approach to metrics and principles is unlikely to materialise in the near future for as long as organisations do not align their strategy and risk approach to global sustainability standards.

Nonetheless, the arrival of an official classification sends a strong signal to the market that policymakers are taking ESG commitments seriously.

Local taxonomies are key to unlocking domestic financing, representing rich seams of capital in countries with plenty of domestic savings.

In turn, vibrant domestic markets can encourage overseas backers to invest more too.

“The local green taxonomy becomes a very important consideration for attracting international investors, because that gives them the clarity on what and how their money is spent, and aligning to their interests,” says Xing Zhang, senior climate policy specialist at the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

“The standard itself can be very powerful in building up the domestic capital market and attracting international finance,” Zhang adds.

AIIB already follows climate financing principles for multilateral development banks. While these guidelines focus more on climate mitigation and adaptation, the bank does compare and complement its approach with other taxonomies or frameworks to help mobilise private capital for specific projects.

Across Asia, lenders and investors will take time to acclimatise to the new details taxonomies provide, limiting the impact of taxonomies in the short term.

In the long term however, official frameworks and definitions can be transformational, laying the foundations for future policies, regulations and subsidies that can reorient national economies.

At this stage, it is important that taxonomies are easy to reference and understand, to increase familiarity and adoption.

Photo by Florian Wehde on Unsplash

Photo by Meriç Dağlı on Unsplash

Broadening of scope for socio-economic development

Bigger challenges lie ahead, as taxonomies extend their reach across more sectors. Regulators will also tighten up definitions and add more granularity to disclosures as the breadth and depth of sustainable solutions expand.

Many jurisdictions are also developing social and transition frameworks, as governments factor more social and economic safeguards into their plans.

Taxonomies that once expressed green ideals are coming down to earth to embrace challenges on the ground.

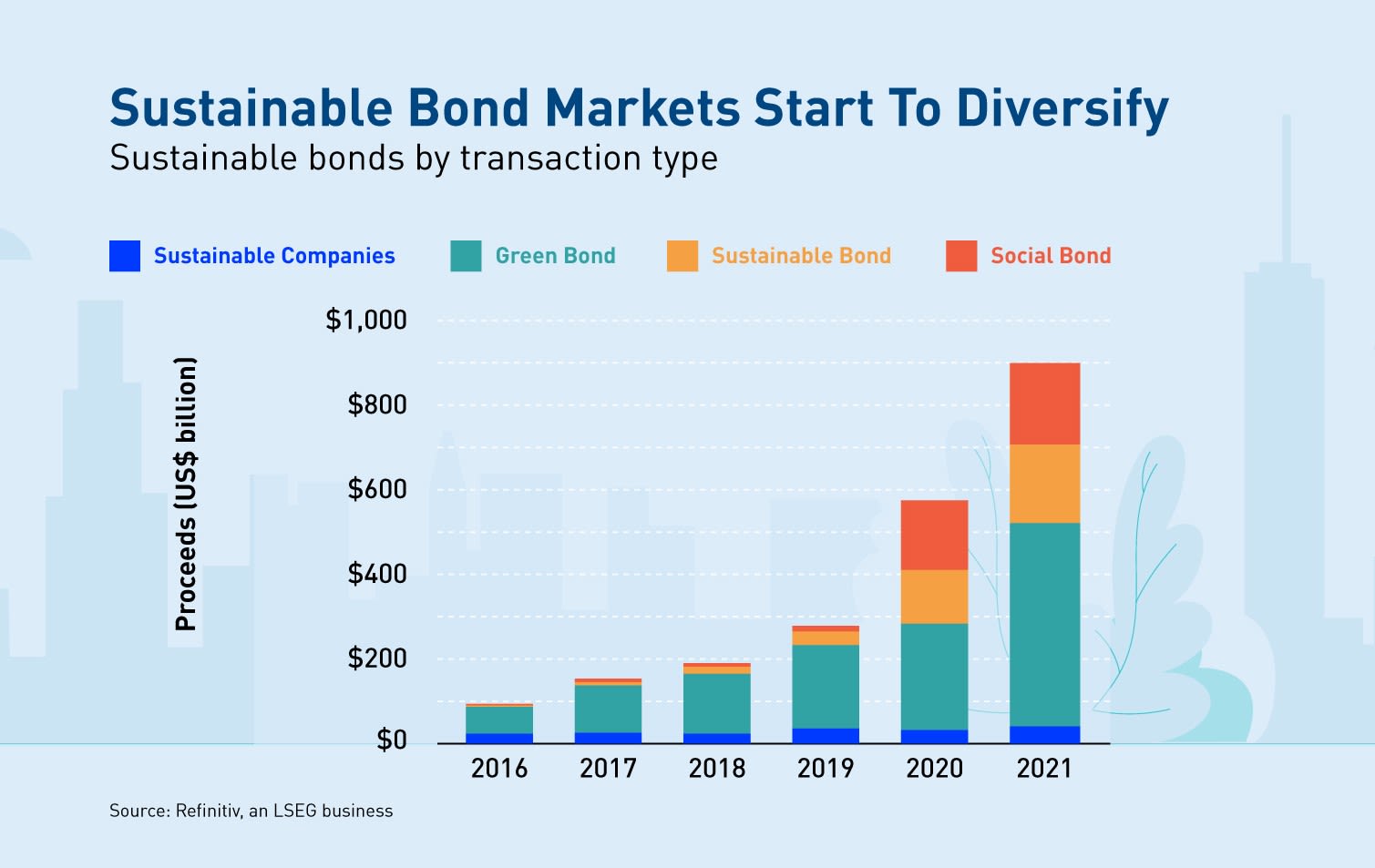

The bond market is following a similar path, especially over the last two years, as a more encompassing sustainability agenda takes shape.

At the same time, the ongoing evolution and increased diversity of taxonomies could surface more points of disagreement, further complicating interoperability and alignment.

The EU, for example, added natural gas and nuclear power to its list of sustainable investments for economic transition earlier this year, albeit with especially narrow allowances for gas.

Other taxonomies also accommodate fossil fuels and nuclear power. More could follow suit as they fill in the details on their transition pathways.

Photo by Barney Yau on Unsplash

Figure 5: Sustainable bonds by transaction type. Infographic by Eco-Business / Philip Amiote

Figure 5: Sustainable bonds by transaction type. Infographic by Eco-Business / Philip Amiote

Interoperability: Connect, Communicate, Coordinate

Getting taxonomies to play well with each other is far from easy.

Ideally, taxonomies share a common base of metrics and classifications. Greater alignment and interoperability can support multinational deals and comparisons, scaling up much-needed funding.

However, this kind of detail is often missing in the first versions of taxonomies - dynamic documents which are meant to evolve over time.

Nonetheless, increased exposure to taxonomies – through international finance hubs and supply chains as well as national frameworks – will encourage continued use and experimentation.

“It's important to be able to get people to sign on,” says Eugene Wong, CEO of Sustainable Finance Institute Asia (SFIA). The Malaysian Central Bank’s taxonomy is already being put to use, for example, by starting with a more qualitative principles-based approach that gives companies little excuse to not engage, Wong notes.

“That starts to get people testing themselves,” he explains. “In fact, this year, the first reports from financial institutions on the application of the Climate Change and Principle-based Taxonomy have been submitted to Bank Negara Malaysia. It gets them used to having to look at these issues. They realise what data is missing, and then they start looking for that data.”

The first priority is getting people to understand what a taxonomy does and why it is needed. That makes banks and corporates more willing to engage with the opportunities and challenges to come.

This is especially relevant for less developed markets, where sustainability competes with core social and economic developmental needs.

“We've got to start this way,” Wong says. “People dip their toes in the water and then feel more comfortable to step in over time, but you've got to start that process.”

Credits

Eco-Business wishes to credit the following people who contributed to the development of this report:

Sharon Seah, Eugene Wong, Wenhong Xie, Joanne Khew, Joseph Chun, Chee Wee Tan, Zhang Xing.

This report was developed and written by Mike Savage and Junice Yeo, with the support of Adeline Chia. Infographics by Philip Amiote.

Special thanks to the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung - Regional Project Energy Security and Climate Change Asia-Pacific (RECAP).