Justine Nolan is a lawyer who has worked at the often uncomfortable intersection between business and human rights for the past 25 years.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The Australian made headlines last July, when six weeks after joining, she and her colleague—migrant rights activist Andy Hall—quit a panel set up by Malaysian palm oil company Sime Darby to work through allegations of forced labour on its plantations. Nolan tells Eco-Business that it is clear that forced labour continues to be a problem for palm oil supply chains, but companies must be willing to open themselves up to scrutiny and uncomfortable truths if they want to make progress. Sime Darby did not seem ready to walk down that road, she says.

Nolan started out her career as a corporate lawyer, then moved to the United States where she worked as an international human rights lawyer. She is now a professor at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in Sydney, where she teaches international human rights in the Faculty of Law and Justice, and is director of the Australian Human Rights Institute.

She also researches business and human rights, with a particular focus on corporate responsibility for human rights and modern slavery. The United Nations’ goal to eradicate slavery by 2030 has helped raise the issue’s profile and Nolan’s field is steadily growing in the public consciousness.

In a video for the Business and Human Rights Teaching Forum, Nolan notes that the term “modern slavery” was mentioned just 41 times by the media in 2000, but more than 6,000 times in 2018.

Some 40.3 million people are currently enslaved around the world — that’s 5.4 victims for every thousand people. To achieve the UN’s target, 10,000 people need to be freed from slavery every day.

“

In the rush to find sources of clean energy, there is a danger that human rights abuses are overlooked.

Justine Nolan, director, Australian Human Rights Institute

Nolan works closely with businesses and non-governmental organisations and has been one of the key figures behind the Australian business and human rights movement. She is a member of the Australian government’s expert advisory group on modern slavery.

Here is how a typical day in her working life unfolds:

6am: I am a morning person, so usually get up around this time and walk the dog and exercise. I live near Bondi Beach in Sydney, so most mornings I start with a swim in the ocean. Last summer I made it my goal to swim in all 45 of Sydney’s ocean pools.

An ocean pool in Bronte, Sydney. Image: Gervo1865_2 - LJ Gervasoni/Flickr

8am: I start work either in my home office or at UNSW by catching up on overnight emails. I make calls to the US or Europe early in my day. This morning I have a zoom call with academics from the US, Europe, Mexico and Colombia, who are all part of the advisory committee for the Business and Human Rights Teaching Forum. The network promotes business and human rights education in universities.

9am: I am giving a lecture to my students on international human rights law. The class is debating how to better regulate supply chains to address forced labour in industries such as apparel, agriculture, and construction. I use the word ‘regulate’ with caution. At times it seems like many corporations are operating within the ‘independent republic of the supply chain’ where there are few hard laws to hold them to account for when things go wrong. And they often do.

We also consider the business and human rights impacts of the clean energy transition, such as the increasing demand for cobalt or polysilicon (used in the production of solar panels) from places such as the Democratic Republic of Congo or Xinjiang, China, where forced labour is often a feature of their supply chains.

Students are passionate about these issues, and keen to know more about the interrelationship between climate change and human rights. In the rush to find sources of clean energy, there is a danger that human rights abuses are overlooked — such as the use of forced labour to produce these goods, or a failure to obtain the informed consent of the Indigenous people on whose land the resources are located. Students are increasingly focused on the social responsibilities of the companies with whom they will be working. This is important as they are our future business leaders.

11am: A meeting with the team at the Australian Human Rights Institute to review our monthly goals and achievements. The Institute was established by UNSW to bridge the gap between academic research and real-world problems. We adopt a practical approach to our human rights work with a primary focus on human rights issues that intersect with business, health and gender. Some of the diverse recent programmes we are working on include tackling issues related to gender justice, and making the right to health a reality. For example, our 2021 report showed that progress on addressing corporate abuses of human rights by Australian companies at home and abroad in the last 10 years has been ad hoc and lacks consistency by both business and governments in creating a work environment where rights are respected.

12pm: As I rise early; I also usually eat lunch early. It is usually taken at my desk as I also use lunchtime to catch up on never-ending incoming emails. I am trying to be better at restricting my email response to set times of the day, but I am still working on this! Many of the emails are logistical or administrative in nature, but I do love hearing from former students who are looking for advice on how to move into a human rights career. I try and connect them with opportunities whether it be applying for graduate study, working for companies on social responsibility or getting experience with human rights-focused NGOs — the more talented people we have working on these issues the better.

“

The next 12 months will be critical to strengthening the corporate practices that underpin mandatory reporting on human rights issues such as modern slavery.

1pm: One of the projects the Australian Human Rights Institute is working on is a collaborative research grant (funded by the Australian government) with four other universities and NGOs to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Modern Slavery Act, and examines the reporting by companies under this new law. The Act was passed in 2018, so we are now at a very early stage of assessing how companies are responding and adapting their practices to better identify and address the risks of modern slavery in their supply chains.

Too often, companies are focused on reforming policies but neglect to consider how this is reflected in their practices. There continues to be a large gap for many between what is promised and delivered. We will soon publish a report on this which shows that, of more than 100 modern slavery statements that we reviewed, 52 per cent of companies are failing to identify obvious modern slavery risks in their supply chain. For example, three in four of the garment companies reviewed that are sourcing from China fail to mention the widely reported risks of state-sponsored Uyghur forced labour in their supply chains.

The next 12 months will be critical to strengthening the corporate practices that underpin mandatory reporting on human rights issues such as modern slavery. To drive meaningful change, companies must examine their business models and procurement practices and start embedding responsible sourcing practices that support workers’ rights, and avoid downward pressure on to suppliers and, ultimately, workers themselves.

3pm: Meeting with representatives from the United Nations Development Programme in Bangkok. We are working with them to develop a training programme to help inform and educate national human rights institutions (NHRIs) across Asia about business and human rights issues. NHRIs provide a bridge between governments and civil society and are key to preventing and remediating corporate abuses of human rights. Too often, the institutions are under resourced. This programme offers them an opportunity to upskill how they might more effectively intervene to improve workers’ rights.

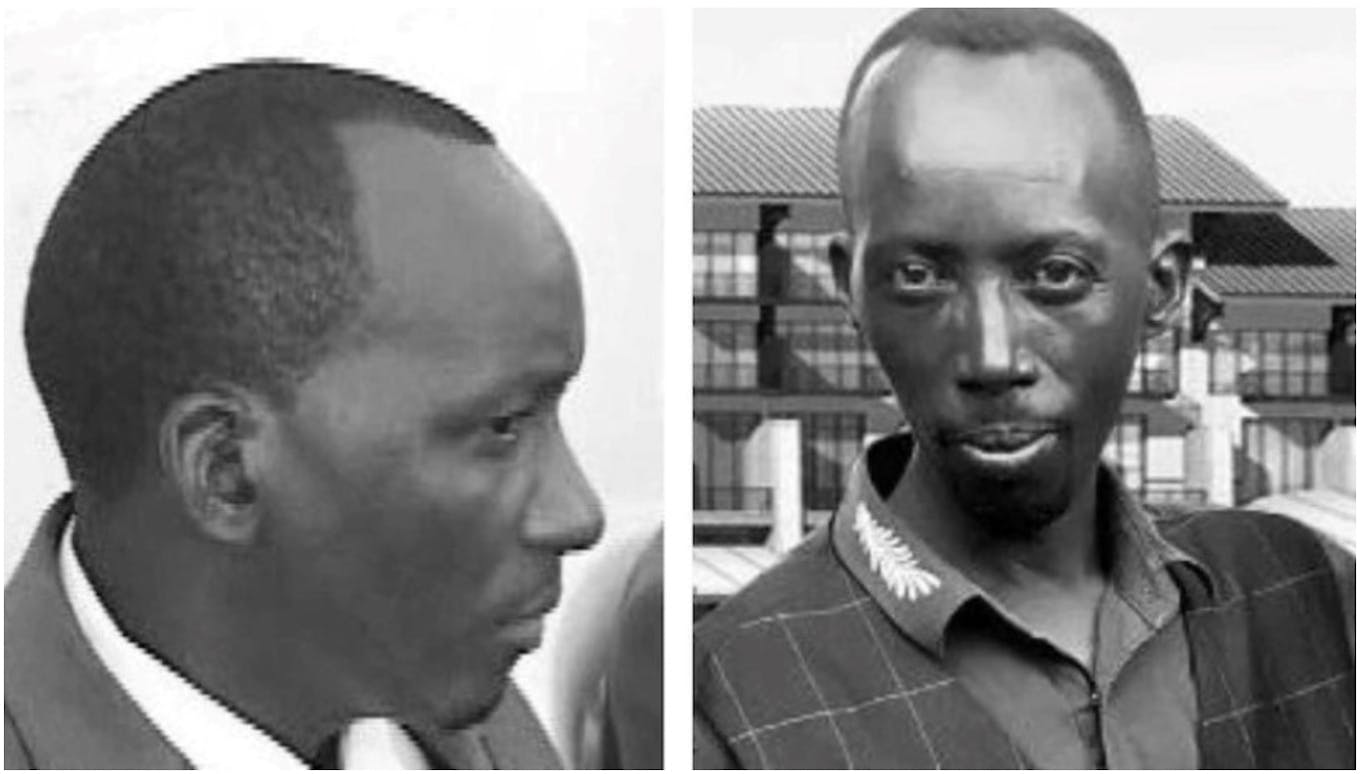

Jean Nsengimana and Antoine Zihabamwe haven’t been seen since 28 September 2019. They were abducted by while on a bus in Nyagatare District, Rwanda. Image: Australian Human Rights Institute

5pm: Meeting with the Australian Human Rights Institute’s Advisory Committee. One of the initiatives that grew from this group is our advocacy with the UN to address the disappearance in Rwanda of the two brothers of one of our Advisory Committee members, Noël Zihabamwe. Mr Zihabamwe is an Australian Citizen who moved to Australia on a humanitarian visa in 2006. In 2016, he was approached by Rwandan government agents who tried to recruit him to become an agent of influence in Australia for the government. After Mr Zihabamwe refused, he was harassed by Rwandan government representatives. His brothers were abducted in 2019. Working with the pro bono support of barrister Jennifer Robinson and law firm Corrs Chambers Westgarth, we have filed a complaint with the UN to seek some form of justice.

6pm: Over the past two years, with much of the world working remotely, I have noticed a tendency for my working days to become longer. On the positive side, it is now more possible to be involved in human rights research and advocacy initiatives as they develop. But the downside is that our nights are often interrupted by late night meetings. I have grown less tolerant of the 3am meetings, but will usually have one or two late night meetings each week that I do after dinner. But if none are scheduled I head for home and if I have time, take one more dip in the ocean to end the day.