Few people can claim to have seen even one of the 42 known species of rafflesia, an elusive, parasitic flower found only in the tropical forests of Southeast Asia.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Botanist Dr Chris Thorogood, who is deputy director of the University of Oxford Botanic Garden, has come face-to-face with nine species of rafflesia. According to a new research paper he authored, 60 per cent of the world’s currently known species are at risk of extinction, mostly due to habitat loss.

“These are some of the most enigmatic and bizarre works of nature on the whole planet. To spend time with a flower like this in the middle of the Southeast Asian wilderness is a very special moment,” said Thorogood.

In a virtual interview with Eco-Business, the botanist describes his long-standing affection for these rare plants, so much so that he even pictures their habitats in his dreams.

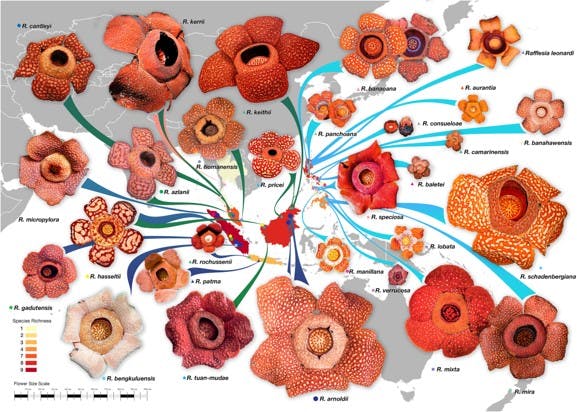

Rafflesias, which are also called corpse flowers because of their strong odour, have been found growing in only five countries in the world, all of which are in Southeast Asia (see map). Although they have been known to scientists for centuries, the flowers thrive in remote and uninhabited parts of the jungle and as a result, are still poorly understood. Because rafflesias spend most of their lifecyle living inside great vines known as tetrastigma, botanists are unable to study the features they commonly use to identify plants, and it has been difficult to compare studies by scientists in the region as they have focused on different parts of the flower, said Thorogood.

Alarmingly, recent observations suggest that some species of the flowers are being eradicated before they are even known to science, the paper said. It predicted that 67 per cent of currently known rafflesia habitats fall outside protected areas.

On top of that, scientists have found it difficult to propagate the plant for study in controlled environments. The most successful instance of propagation was done at Indonesia’s Bogor Botanic Garden in West Java, where a clipping of an infected tetrastigma vine was grafted onto another plant.

Thorogood has been working with University of Philippines associate professor Pastor Malabrigo Jr and researcher Adriene B Tobias, to replicate this in the Philippines.

Rafflesias are the world’s largest flowers and found most abundantly in Indonesia and the Philippines, but many species are now on the brink of extinction. Image: People Planet Profit

Pre-trek paperwork

Months of logistic preparation and paperwork for permissions are needed before entering the field, as the habitats in which rafflesias grow are often highly protected, remote and inaccessible, said Thorogood.

However, there are no guarantees that the team will find flowering rafflesias, even after days of travelling. “Sometimes you can travel for a long way and all you find are the buds that haven’t opened,” said Thorogood. Due to the remoteness of the sites, the researchers try to avoid staying in the jungle overnight.

To improve their chances of success, field trips are timed between March and April, which is when most rafflesias tend to bloom. Some species show seasonality depending on rainfall, but they are mostly rare and unpredictable, the botanist said.

Because of this unpredictability, however, research can also be quite spontaneous. “Sometimes there’ll be an anecdotal report of someone finding rafflesia and that information will trickle down to whoever runs the forest patrols and eventually to us (the researchers). So there’s a lot of coordination and Facebook messages that goes on behind the scenes,” said Thorogood. As much as they plan treks in advance, he admits that field work can be “quite last minute” and involves a lot of luck.

Different species of rafflesia vary in size and smell. Clockwise from top left: Rafflesia banaoana in Kalinga, Philippines; Rafflesia arnoldii in Sumatra, Indonesia; Rafflesia bengkuluensis in Sumatra, Indonesia; Rafflesia kemumu in Sumatra, Indonesia. Images: Chris Thorogood

Fortunately for the scientists, local conservation authorities have been largely flexible and hospitable. “They’ll tell us there’s a sighting the day before and we’ll meet them in their office,” said Thorogood.

Once those pieces fall in place, the team is ready to set off in search of rafflesias.

Here’s what a day in the forest looks like for Thorogood:

Day before: We are usually tired by the time we arrive at the site because there’s a lot of driving involved. In Luzon, Philippines, we travelled for two days to reach a remote forest in Kalinga. My colleagues in the Philippines have different sleeping patterns — they don’t sleep as much as I do, so they can survive on very little sleep!

5am: We get up at dawn and wash, typically with a bucket of cold water and a dipper. Then we get into our field clothes and a lot of insect repellent, which I’ve learnt over the years is very important.

There’s a sense of excitement and anticipation among the group because you don’t know what you’re going to find and whether you’re going to be successful. Among the group, there is a lot of discussion about where we are going to go and how long it will take. Usually I don’t understand any of that because it will be in a language that’s foreign to me, like Tagalog, or the local dialects of Indonesia.

On my most recent field trips in the Philippines, the group comprised myself and my assistant, (University of Philippines researchers) Pastor Malabrigo Jr and Adriene Tobias, forest rangers, about five or six men from the local Indigenous community and sometimes even their dogs.

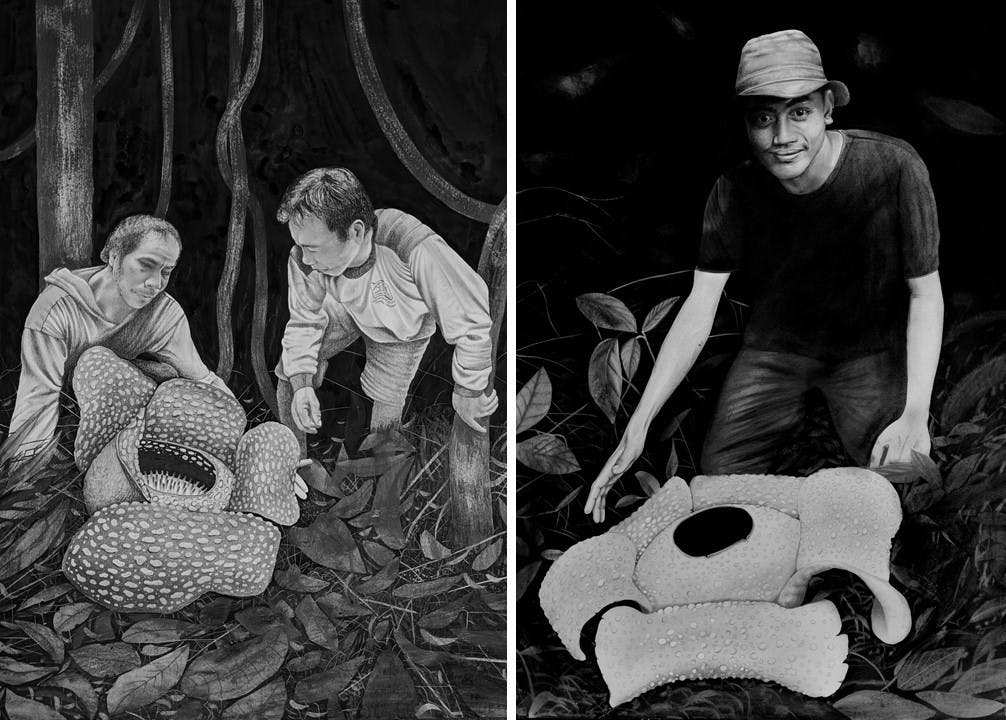

Deputy director of University of Oxford Botanic Gardens Dr Chris Thorogood makes rough sketches of the people he works with in the field, taking a week or two to finish them upon returning home. Image: Chris Thorogood/ Pathless Forests

5.45am: It’s best for us to start our adventure at daybreak, because that gives us the longest period of time to reach the interior of the forest and return, ideally within the same day. There are some occasions where we would camp in the forest, but in my field trips, because we want to see as many populations as possible, we would try to opt for multiple locations that are the most accessible.

I usually find the first half hour is the most difficult part of the trek, because I have to get acclimatised (to the jungle). It’s hot, it’s sticky and the plants get in the way. But after that, I get used to it.

The Indigenous Peoples are invaluable, because as I mentioned, these forests are often very inaccessible. You need someone with machetes who can cut a tunnel through the difficult terrain, or create a path where there isn’t one.

Sometimes none of us will know exactly what way to take, or what we’ll find when we get there (since we might be following anecdotal reports.)

6.30am: The conditions can be quite difficult. Sometimes it can get very, very hot. The lowlands are humid, but in mountain environments, the air can become quite fresh and pleasant. It can also be pouring with rain, depending on the time of the year.

Chris Thorogood’s painting of rafflesia and its bud in Kalinga, Philippines. Image: Chris Thorogood

I was once on a rafflesia expedition during monsoon season, although we managed to dodge most of the rain that season. But then there are dry seasons where I have been absolutely drenched.

11am: We might stop for a break around midday. We often have to cross rivers as well. One of the things I’ve grown used to is to just walk straight into the river – you have your field clothes, you have your relevant footwear, so you just walk straight in and hope you don’t fall over.

1pm: We hope to find a rafflesia population by around the middle of the day, after lunch, so that we have time to get back before sunset. When we reach the location, we’ll spend about an hour there with the flowers if we can, measuring them, taking notes, taking photographs and enjoying the flowers as well. Sometimes after a long trek, it can be quite emotional, actually, to see such a striking work of nature and something so extraordinary.

We then examine the flowers and collect data on them. Despite them being the world’s largest flowers, we actually have to zoom in to the smallest features to be able to examine them properly. Size is not actually the best feature to measure (for taxonomic purposes) — what we want is a consistent approach to collecting data on rafflesias across different species, so we look for stable features such as the processes, which are the small white spines in the middle of the flower, or the ornamentation of the petals.

A rare glimpse into the interior of Rafflesia arnoldii shows small spikes in the centre of the flower, which are one of several ways taxonomic botanists categorise the flower. Image: Chris Thorogood

My colleague Tobias is a young and very talented taxonomic botanist who has been studying this and trying to find stable but potentially neglected features. You need a very detailed and meticulous approach to studying it in order to be a good taxonomist. The more information we can gather, the better.

The smell of the flowers varies greatly. Of the 42 species, most of them don’t smell too bad, so you can spend more time in their presence. If you get close, the smell can be unpleasant but not terrible. Of the nine species I’ve seen, only two have smelled really bad: the Rafflesia patma in Java, and another one in Sumatra.

In the Philippines, we had permission to collect a small amount (of the tetrastigma) sustainably from a known population, which we took to a new reserve and tried to replicate exactly what was done in Bogor. We don’t want to experiment too much because there’s a limited amount of material.

3pm: We have to regulate our time so that we can get back (before sunset, which happens at around 6pm) because we don’t want to get lost in the forest. We go through very difficult vegetation sometimes, so the forest rangers would have slashed little marks in the trees so that we have markers to find our way out.

7.30pm: How we celebrate (after a trek) depends on where we are. In the Philippines you celebrate with a beer. My collaborator Pat (Pastor Malobrigo) is able to summon beer even in the most remote forests. I don’t know how he does it, but they seem to appear from somewhere. If I’m in a different part of the region, such as Indonesia, then we might have nice food instead.

But overall, everyone is very happy and excited. We spend time looking at the photographs on each other’s phones and comparing what we managed to photograph of our findings.

9pm: When I go to bed and close my eyes, I still see the forest and the same trees I’ve been looking at all day long.

Upon returning from the field, Thorogood spends time documenting the people and plants he encountered in detailed sketches and paintings. He explains that art is how he captures the realisation of his childhood dream of travelling to Southeast Asia to experience tropical forests in person.

“When I’m old and unable to do any fieldwork, I will look back at these moments in my life as the ones that stand out from the rest,” said Thorogood. “I will always remember in very sharp detail the moments I spent with these extraordinary flowers.”

He spends many weeks completing detailed watercolour and oil paintings of the flowers, but also produces pencil sketches of the people he made his field trips with.

“I wanted, in some small way, to try and acknowledge the wonderful people that I’ve worked with here who have enabled me to have those adventures,” he said.

More of Thorogood’s artwork and his personal reflections can be found in his book Pathless Forest, which will be published in March 2024.

Chris Thorogood (middle row, third from left) and his colleagues in the Philippines after propagating Rafflesia. Image: Chris Thorogood