Narratives about nature in Singapore’s history textbooks over the last four decades portray the natural world as a realm that should be feared, controlled and exploited, a recent research article has revealed.

Titled Nature, Disappeared: Anti-Environmental Values in Singapore’s History Textbooks, 1984-2015, the article found that the non-human environment has mostly been represented from a utilitarian perspective, as a reservoir of natural resources, something to be feared, which is described in the paper as a “negativistic” value, or something that must be conquered and controlled in the service of progress (a “dominionistic” value), rarely portraying it in any other light.

Although only 20-29 per cent of history textbook pages contain human and non-human interactions, merely increasing the total number of environmental narratives is insufficient—instead, different representations of human-environment relationships and interactions must be included, the authors argue.

“What this means for students in Singapore is that it will be harder for them to realise that they are embedded within or dependent on the environment. As the history textbooks move into present day, human-environmental interactions were mentioned less and less,” said Neo Xiaoyun, lead author of the article.

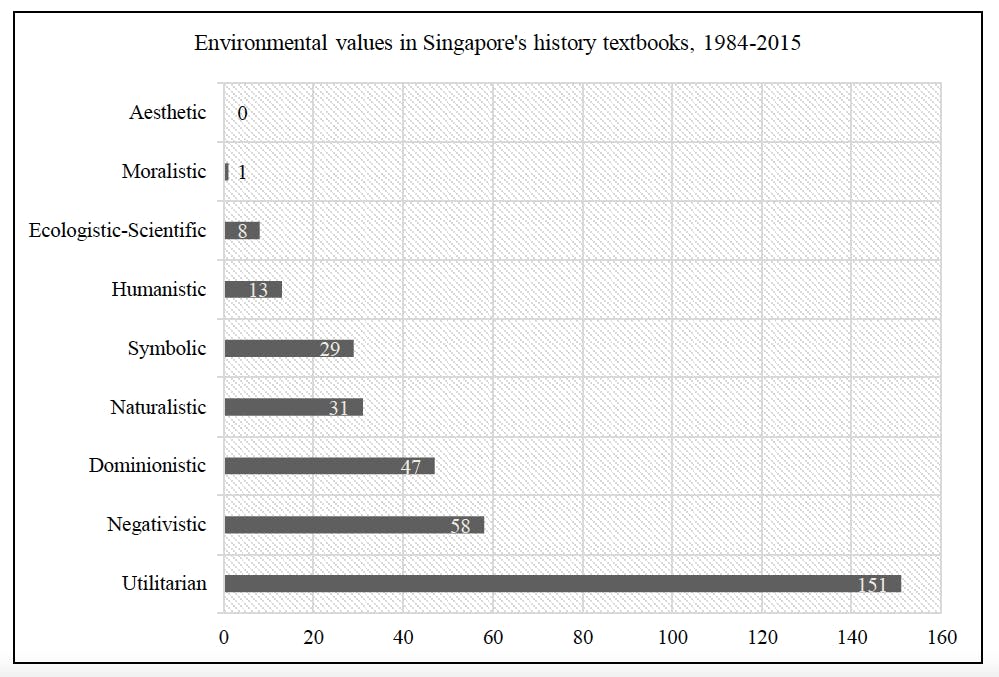

The authors analysed Singapore’s history textbooks using ecologist Stephen Kellert’s taxonomy of nine basic values towards the non-human environment, which include: utilitarian, dominionistic, symbolic, negativistic, naturalistic, moralistic, ecologistic-scientific, humanistic, and aesthetic values.

Environmental values in Singapore’s history textbooks, 1984-2015. Utilitarian values-the idea that the non-human environment is a material resource for humans to exploit to satisfy needs and desires-is the dominant narrative.

“Narratives bridge and translate dominant ideas into values, behaviours and policies, promoting some outcomes while omitting other options. The prevailing narrative structures do more than factually misrepresent environmental history; they constrain visions of likely or possible socio-ecological futures, in Singapore and elsewhere,” the authors wrote.

“These portrayals of the environment are probably not intentionally conveyed, but that’s precisely why we need to take note of it—these problematic environmental values are imbibed without realisation,” lead author, Neo said.

By focusing heavily on utilitarian, negativistic and dominionistic representations of the environment, the history textbooks marginalise awareness of and concerns about socio-economic injustice, the long-term costs of development, and mass extinction, among other critical topics, the authors argue.

In March this year, Singapore’s Ministry of Education announced the enhancement of the teaching and learning of sustainability within the science and humanities curriculum, including environmental concerns in Singapore and related innovations in the region, and sustainable urban development.

Instead of analysing geography or science textbooks that have explicit mentions of the environment, the authors decided to examine history textbooks as they believe that climate education should not be restricted to the sciences.

“Sustainable development is not the full picture. We need to look at the arts and humanities and what those subjects are teaching students about national narrative and what it means to be a Singaporean. These things—discourse, values and attitudes—are conveyed through history textbooks,” said Neo.

“When climate change is relegated only to geography and the sciences, and is taught in passive language, without any attribution to people, systems or organisations, this makes it hard for students to pinpoint solutions. The effects of climate change are happening, but who’s causing it?” asked Neo.

A graduate from Yale-NUS College, Neo mentioned that despite the closure of the first liberal arts college in Singapore, the interdisciplinary education that the university embodied was what enabled this research and should also be how climate education is taught in schools.

“By being able to draw from different disciplines, and by working with a professor who does not just specialise in history or environmental studies separately—but is able to marry the two—these are valuable factors that propelled my research into something more,” she said.

Envisioning the future history syllabus

“Moralistic and humanistic values are probably the two most important values that drive individuals to protect the environment, and the ideal textbook should include these narratives,” said Neo. The moralistic value posits that there is an ethical concern and belief that the non-human environment has spiritual and/or moral standing— that’s the one that will probably lead to conservation.

She said that adding the history of islander heritage, people whose livelihoods depend on the land, and therefore had practices and beliefs around the land, would be beneficial for students. “As I interact with Orang Laut SG or Wan’s Ubin Journal, I realise that the stories they share about Singapore’s history are so important, but that’s not something that the curriculum setters can bring to the table,” she said.

In addition, narratives with ecologistic-scientific values include Singapore’s huge contribution to zoology and botany. “There’s a lot of existing research on this topic, for example Tim Barnard’s work. It’s out there, it’s just not being taught,” said Neo.

Neo mentioned that what is underplayed in history textbooks is how biodiverse Singapore is, in terms of both terrestrial and marine environments. She guides intertidal walks and people are amazed at the biodiversity that exists in Singapore, “but it’s just 20 odd per cent of what Singapore used to have,” she added.

“I am hopeful that more environmental history can be taught, especially since some aspects are beneficial towards current sustainability efforts. One example would be how Singapore used to be an agricultural nation, which could aid in our contemporary efforts towards self-sufficiency. I think this narrative could help Singaporeans realise that growing our own food is something rooted in our heritage,” Neo said.

Other important narratives that will be increasingly pressing is the refugee situation in Southeast Asia, Neo said. While these are difficult topics, she believes that children can learn to understand them and process more complex emotions.

The Human X Nature exhibition is a good example of a balanced portrayal of Singapore’s environmental history, said Neo. The exhibition, which runs till the end of September, includes stories of the people who lived in Singapore’s rivers—the Orang Seletar and Orang Kallang—and brings to life the extinct animals through taxidermy.

“Past transformation has come to shape our present understanding of nature and the ways that we interact with it,” said Neo, recalling a quote from the exhibition. “First we need to understand what’s Singapore’s past transformation. If we don’t even know where we began and what has transformed, we cannot form our current identities and relationship to the environment.”