Barangay Alaska is a coastal village in Aringay, La Union, a bucolic municipality 244 kilometres north of Manila. In this village, 306 families are fighting to protect their homes, and their existence as a people, from vanishing into the sea.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

As of 2010, Alaska had a land area of 237 hectares in its lone community called Berlin. In the late 1980s, there used to be two communities in the area: Berlin, and Nagpanauan. But the latter community sank into the ocean when a devastating earthquake in July 1990 caused the land to cave and sea levels to rise.

Since then, residents observed that the sea has continued to eat away at their shoreline.

Leticia Ferrer, a 42-year-old schoolteacher, still remembers where the last four school buildings in Alaska once stood. Crashing waves destroyed three of the buildings, while the ocean completely submerged the fourth one. “This is the fifth time we’ve moved the school,” the grade six teacher says. “If you swim towards that part of the ocean, you will see the old school building underwater,” she tells Eco-Business.

But the shoreline around the new Newbern Elementary School, where 158 students are enrolled, is also receding, observed residents. “I fear the sea will engulf this school building, too,” Ferrer says.

Berlin, Alaska Aringay La Union schoolteacher Leticia Ferrer points to the direction of the sunken school building.

Long-time Alaska resident Editha Rulloda, 59, has the same concerns. She points to the water less than a metre away from the sand bags that surround her home. “We have nowhere else to go,” she says.

Typical houses in Alaska are built with lightweight materials: Pieces of cardboard, tin sheets, and tarpaulin patched together, mostly salvaged from residents’ previous homes. The cost of relocation is a financial burden, and so they cannot afford to use concrete and can only build homes with about four square metres of space, with no plumbing. They have to share two public toilets. Washing clothes and cooking meals are done in common outdoor spaces.

The residents know that these problems will not end until their root cause is addressed: their existence as a community has been made fragile by the rising seas.

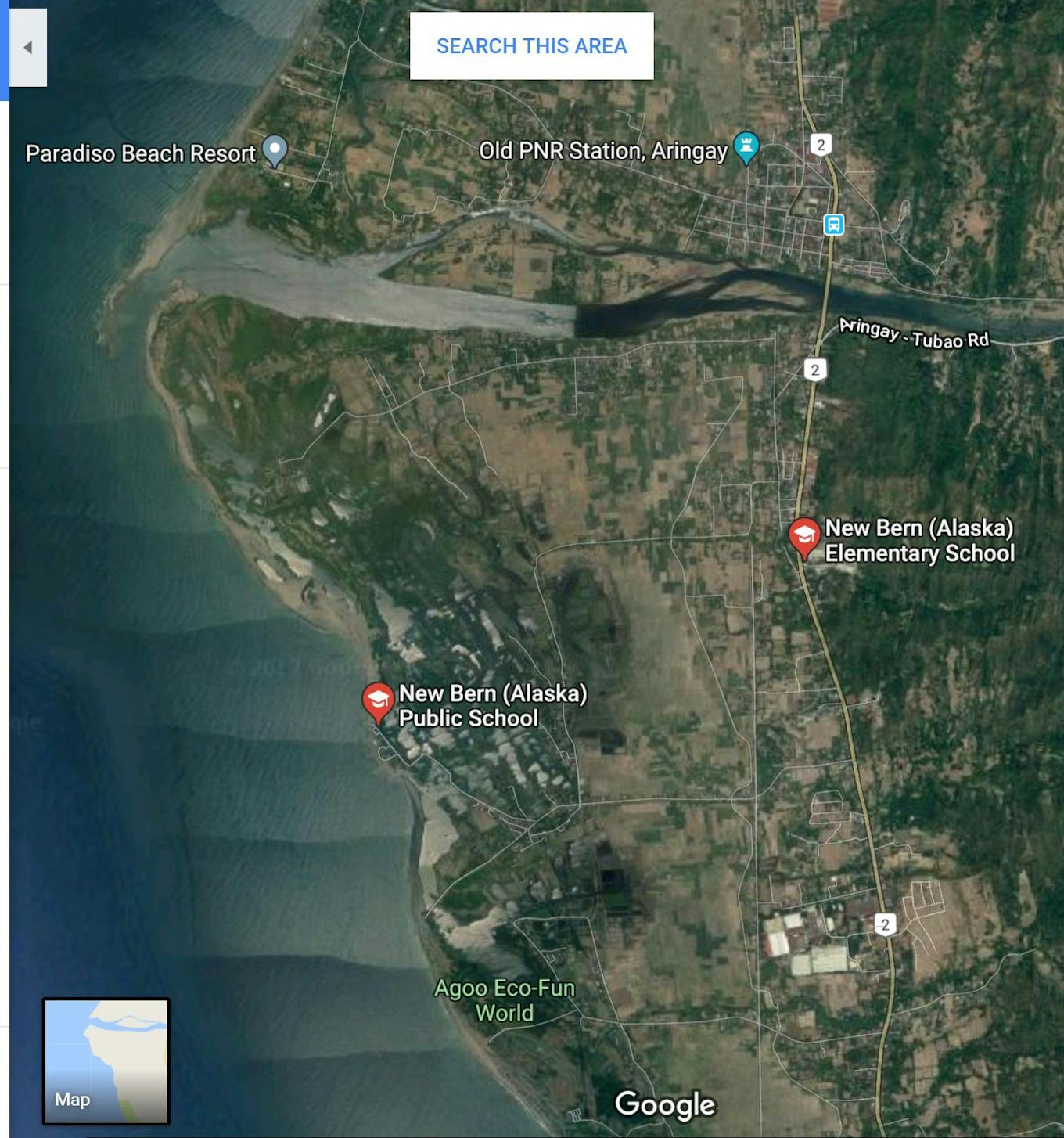

Map of Barangay Alaska, Aringay La Union. The New Bern Elementary School featured in this story is the one closer to the shore. Another school of the same name was built near the highway.

Despite this, village chief Jose Rulloda, 54, offers his house to double as the community gathering place. It is here where they discuss their challenges: Water from the pump has become salty, and fresh water sold from the neighbouring village is costly at US $1 a bucket. This lack of water has resulted in poor sanitation and incidences of diarrhea and other diseases.

“Our people want to permanently relocate to a safe place where there is livelihood,” says Rulloda. But, he wonders:”Who’s going to help us?”

Climate change a factor in sinking Alaska

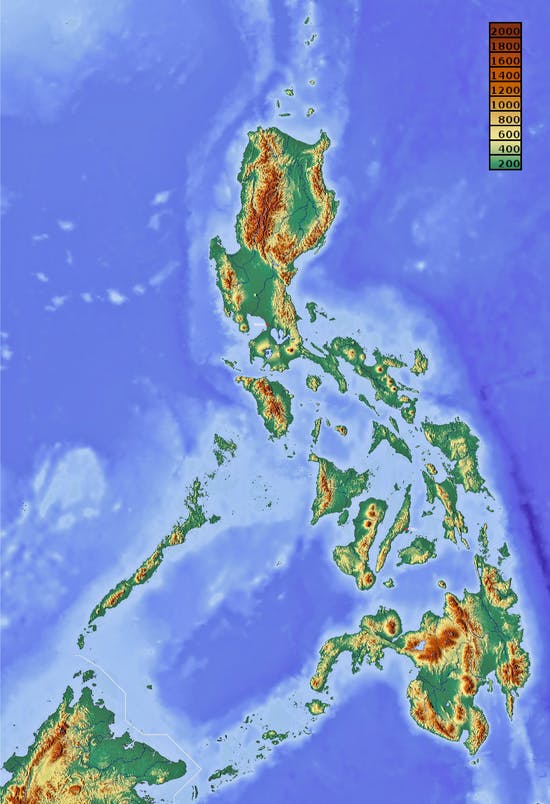

Scientists say that climate change could have a hand in Alaska village’s predicament, and that in fact, more coastlands in the Philippines will be submerged due to global warming.

A 2015 study published by the University of the Philippines projected that more than 167,000 hectares of coastland—about 0.6 per cent of the Philippines’ total area—will go underwater, especially in low-lying island communities.

Citing data from the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO), it showed that water levels around the Philippines are rising at a rate almost three times the global average. This is due partly to the influence of the trade winds pushing ocean currents.

On average, sea levels around the world rise 3.1 centimetres every ten years. Water levels in the Philippines are projected to rise between 7.6 and 10.2 centimetres each decade, the study said.

The Philippines has 7,107 islands and 18,000 km of shoreline.

Yolanda Aguilar, officer-in-charge of the the Marine Geological Survey Division (MGS) of the Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB) agrees that human-induced climate change is causing warming ocean temperatures and rising sea levels.

“With global warming, sea level rise is enhancing coastal erosion not only in Aringay but in all the coastal areas of the Philippines. This could endanger more communities in the country,” she says.

What’s happening in Berlin, Alaska is what climate scientists describe as slow-onset climate change event, such as sea level rise or ocean acidification.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)’s technical paper on the subject says that the negative effects of slow onset events are already affecting developing countries and the resulting loss and damage associated with slow onset events is likely to

increase significantly, even assuming that appropriate mitigation and adaptation action is undertaken.

In contrast, the MGS says that liquefaction, not climate change, caused the sudden sinking of Nagpanauan. Liquefaction causes soil to lose its strength in the presence of a stress factor such as an earthquake.

Loss and damage: Making polluters pay

Sinking Barangay Alaska depicts a scenario that is occurring in coastal communities in many parts of the world where rising sea levels are forcing poor people to migrate.

In global climate negotiations, the need to help these vulnerable communities is highlighted in discussions of “loss and damage”, which is UN language for the impacts of climate change that people have not been able to cope with or adapt to.

Julie-Anne Richards, a UK-based campaigner for and author of the Climate Damages Tax, an initiative seeking to make rich countries and the fossil fuel industry pay for climate damage to poor and vulnerable communities, explains that loss and damage is the third pillar of climate change finance, added to mitigation and adaptation.

Loss and damage funding is required when both mitigation and adaptation have failed to help communities deal with climate impacts, explains Richards.

The New Bern Elementary School in Alaska, Aringay La Union Philippines.

“The climate change that we are experiencing now is a result of the historical emissions of rich countries,” she argues.

Richards said that the fossil fuel industry is also to be held responsible because it is the source of roughly 70 per cent of carbon dioxide emissions in the atmosphere.

“Oil, coal and gas companies that extract fossil fuels from the ground sell it for trillions of dollars of profits a year, and essentially outsource the true cost of their products onto the poor people who face climate change loss and damage,” she says.

Rich countries guilty of “cruel double standard”

Considering the climate change-related loss and damage have occurred over the past years, there is a need to raise US $200 to $300 billion a year in loss and damage funding, Richards says.

Rich countries and fossil fuel companies should not be as scared as they are about this, Richards advises, adding that airline tax for international flights, aviation and maritime fuel, and high volume financial transactions could all be potential sources of funds, instead of national budgets.

But at COP23, rich countries like Australia and the EU rejected the proposal to include financing in loss and damage negotiations because “not every disaster is caused by climate change.”

Greenpeace Southeast Asia executive director Yeb Saño rebukes this position. While it is true that not all disasters are caused by climate change, extreme weather and slow-onset events can be clearly attributed to climate change, he says.

“Logic follows that if certain events can be attributed to climate change, then finance should be very much part of the conversation. Otherwise, they are guilty of a cruel double-standard,” Saño says.

He further argues that human-induced climate change does not have to be the singular cause for disaster for any loss and damage discussions to apply.

“The science of attribution now has the capability to calculate which part of an extreme event can be attributed to climate change,” Saño says.

Saño is referring to an emerging body of science authored by researchers from the University of Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute known as Probabilistic Event Attribution (PEA), which deals with examining

to what extent extreme weather events can be associated with past anthropogenic emissions.

“Rich countries promised to pay loss and damage finance in 2013 when they set up the Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM) for loss and damage, in the Paris Agreement in 2015, and again in Marrakesh in 2016,” Richards says. “We have to make sure they keep their promise so that people in the frontlines of climate change will get the money they need to deal with the worst impacts.”