“Look, the peat here is so deep” 61-year-old Preecha Chimtong, a smallholder farmer growing oil palm on his 49-rai (about 20-acre) farm in southern Thailand’s Chumphon province.

The land is spongy underfoot, dark black and sodden, and Chimtong takes one of the metal tools used to pick up the oil palm bunches and easily pushes it deep into the ground to demonstrate.

Chimtong has roughly a thousand oil palm trees, and many of them are grown in a mangrove forest conservation area – the Pru Kaching peat swamp – in Paklong area of Batiew district. Chimtong is one of hundreds of smallholders who are involved in this case of land conflict in a protected area.

Pru Kaching was declared a National Reserve Forest in 1965, under the control of Thailand’s Royal Forest Department.

Then, in 1987, when the Thai government established laws related to mangroves under a Cabinet Resolution, Pru Kaching was designated a “mangrove forest conservation area,” thus falling under the responsibility of Thailand’s Department of Marine and Coastal Resources (DMCR). It was later expanded in August 2000.

Seasonal workers on smallholder Chimtong’s farm. Chimtong has roughly a thousand oil palm trees, some of which are grown in the Pru Kaching peat swamp forest, a mangrove forest conservation area. Image: Demelza Stokes via Mongabay.com

But by then, according to Narong Pholla-iad, governor of Chumphon province, a third of the 4581-rai (approximately 1811-acre) area had been encroached upon by smallholders who cleared and converted the land to grow oil palm.

In 2014, the Thai government launched a forest reclamation operation led by Pholla-iad to reclaim land in Pru Kaching. However, many worry it’s too late for hundreds of acres of peat swamp that have already been planted with oil palm trees.

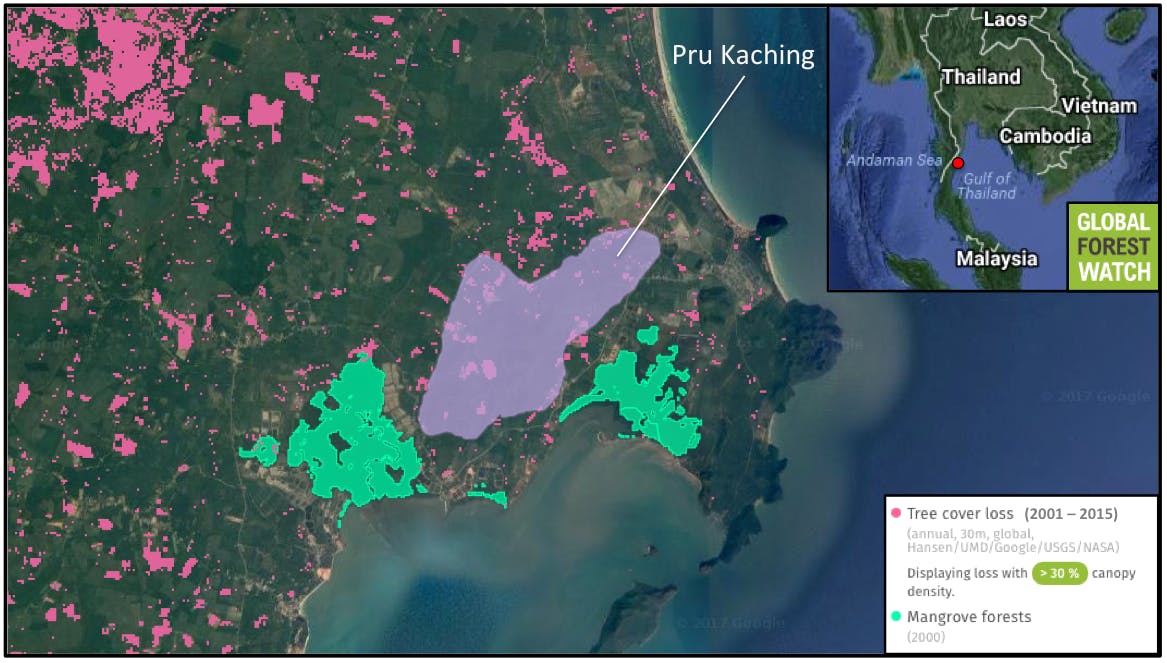

Satellite imagery show large swaths of cleared area in Pru Kaching, and data from the University of Maryland indicate the forest lost around 20 per cent of its tree cover between 2001 and 2015.

These numbers, which reflect both deforestation and plantation clearing, have ramped up over the past few years, with more tree cover lost in 2014 and 2015 than over the previous 13 years.

The Pru Kaching peat swamp forest and surrounding area have experienced significant tree cover loss since 2001.

When Mongabay reached Sorapob Thaninpong, chief of the Department of Marine and Coastal Resources 43rd conservation office, and in charge of Pru Kaching, he declined to comment, saying that the forest reclamation operation in Pru Kaching remains ongoing.

The Director-General of the Department of Marine and Coastal Resources also declined to comment. But a middle-rank official with the department who wished to remain anonymous said that Thailand’s peatlands have become a grey area in terms of which department is responsible for their protection.

The law used to enforce the protection of peatlands is still implemented by the Royal Forest Department and the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation, but Pru Kaching’s conservation has been entrusted to the Department of Marine and Coastal Resources, which has no authority to enforce the law against encroachers, the official said.

In the meantime, jurisdictional confusion has hampered efforts to protect the Pru Kaching peat swamp. The designation of peat swamps and mangroves is “definitely a lot more complex,” said Maurizio Farhan Ferrari of the NGO Forest Peoples Program.

According to Ferrari, who has worked with indigenous communities within or bordering protected areas in Thailand, “there seems to be a lack of coordination between the different agencies when addressing issues related to landscapes that are composed of both terrestrial and coastal or marine ecosystems.”

Thanit Nuyim, Director of Thailand’s Department of National Parks, Plants and Wildlife Conservation (DNP) at Regional Office 6 in Songkhla, has conducted research for 25 years on southern Thailand’s peat swamps.

He told Mongabay that the main role of the DNP regarding protection of peat swamps is both to preserve existing conservation areas and endeavor to declare new ones, as “the declaration [of new areas] will allow the DNP to deploy officials to protect them.”

The problem with developing on peat

Peat is a type of soil composed of partially decayed organic material such as vegetation that accumulates over time in a water-saturated environment lacking in oxygen.

Peatlands are characterised by a thick layer of peat, often several meters deep that can take thousands of years to form.

Peat swamp forests act as massive carbon sinks, and when they are drained, carbon that has been slowly captured over the centuries it takes the peat to form is suddenly released into the atmosphere.

A group of scientists recently uncovered the world’s largest tropical peatland in the Congo basin, thought to store the equivalent of three years’ worth of the world’s total fossil fuel emissions.

The draining of peatlands can also lead to widespread subsidence, or sinking, as the organic matter rapidly decompresses and decomposes, ultimately rendering land unsuitable for agricultural or community development, according to NGO Wetlands International.

Across Southeast Asia, peat swamp forests have been cleared, drained, and burned away, often replaced by monocrop plantations or construction projects.

Malaysia and Indonesia’s vast peatlands have been significantly reduced by large-scale draining and drying, leading to huge forest and peat fires across the region – such as the 2015 haze crisis that scientists say may have led to the premature deaths of 100,000 people.

The event subsequently led Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo to ban the clearance and conversion of peat swamps.

Estimates from the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) place Thailand’s tropical peatlands at between 64,000 and 75,000 hectares, found mostly in the south.

While the UNDP pegs Thailand as having one of Southeast Asia’s strongest protected areas systems, just some-30 per cent of Thailand’s peat swamps had been included in protected areas by 2012.

A sign erected in the Pru Kaching peat swamp reads: “This canal marks the boundary to prevent further encroachment into this mangrove forest conservation area. It does not mark the boundary of the national reserve forest. Please assist in the continued preservation of this area.” Image: Demelza Stokes via Mongabay.com

Of the existing peat swampland in Thailand, “not all is considered healthy” said Thanit, adding “fire is a major cause [of] peat swamp damage.” In 2010, 3,200 hectares of peatlands were affected by fires in the Kuan Kreng swamp forest in Nakhon Si Thammarat province alone (which contains 4.3 per cent of Thailand’s total peatlands), according to research.

The UNDP puts blame for the region’s peatland fires on the draining and drying of peatland to make it more suitable for agriculture, finding 1,000 hectares in Kuan Kreng had been drained and converted for oil palm by 2014.

Difficulty separating people from the land

In Thailand, sources indicate corruption and lack of official protection and enforcement may have facilitated human encroachment into the Pru Kaching peat swamp forest.

A complex land tenure situation further complicates the case, as some oil palm farmers, like Chimtong, were already living within or growing their crops in the peat forest before it was declared a protected area.

Narong Pholla-iad, governor of Chumphon province, said he and his colleagues who are conducting forest reclamation operation are planning to use government aerial photographs taken in 2002 to ascertain how long smallholders had been on the land.

“If they were there before [the designation of protected areas]…they will be allowed to stay with some conditions, such as paying rent to the state,” he told Mongabay.

“They can keep farming the land, pass down that land to their children. But they can’t sell that land to anyone.”

Thai media have blamed investors and local politicians have for using farmers as proxies by which to encroach upon protected land (Mongabay was unable to independently verify these allegations).

This practice has been alleged elsewhere in Southeast Asia, where private investors distanced themselves from the process and aftermath of oil palm farming, leaving local farmers responsible for the damage.

Bribery and corruption often affect land ownership in Thailand, with the Department of Land ranked the most corrupt in the Thai bureaucracy, according to a survey done by Chulalongkorn University in 2014.

Local Land Offices, which come under the Department of Land, are the key agencies for all transactions and documentation involving the sale or purchase of land, and can charge a fee for their services. But the survey revealed that land officials often demand extra money to speed up work or legalise documentation.

“We received complaints from local people to investigate land ownership due to people encroaching on land in the Pru Kaching peat swamp,” Pholla-iad told Mongabay.

“Our investigation found that 73 land plots, covering about 500 rai (198 acres), were occupied with legal land ownership documents.

Another 81 land plots, covering more than 1,300 rai (514 acres), have no legal land documents.” Mongabay was unable to independently confirm if the “legal land ownership documents” covering the 500 rai were indeed legally obtained.

Thailand’s National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO – the junta that has ruled the country since a coup d’etat in May 2014) issued an order (no. 64/2557) on June 14, 2014, instructing government agencies to halt deforestation and encroachment on forest reserves nationwide.

Following the order, Chumphon governor Narong Pholla-iad said some of the encroached land at Pru Kaching was reclaimed in an operation conducted September and October, 2014, by the Thai army and the Internal Security Operations Command (a Thai military unit dedicated to promoting “national security”).

A laborer on Chimtong’s farm loads oil palm bunches onto a vehicle. The palm fruit are then sold to local refineries across southern Thailand. Image: Demelza Stokes via Mongabay.com

Pholla-iad told Mongabay that while much of land encroached by investors had been reclaimed by the government, some may still remain in oil palm production.

“Following the order by the NCPO, we will have to look at the landowners of the 1,300 rai (514 acres),” Pholla-iad said. “Are they poor? Do they pay taxes? If they are poor, we will find solutions. But we will reclaim the land, especially from the investors.”

But some, like smallholder Chimtong, take issue with the efforts by the Thai government to reclaim land in Pru Kaching.

“I think the reclamation operation is not fair to local villagers,” he said. “Many years ago, there was not a forest declaration here.

Suddenly, the officials arrived and tried to declare a forest zone despite villagers having been here for decades. More than 100 villagers have been affected by the operation.”

Chimtong also claims that officials turned a blind eye to the encroachment until receiving an official order from Thailand’s new military government, which also pledged to crack down on corruption and created the country’s first dedicated anti-corruption court last year.

Some human rights activists allege that despite a subsequent NCPO order (66/2557), which stated that forest reclamation operations carried out on the basis of order 64/2557 must not impact upon the poor, many forced evictions of impoverished forest-dwellers have still taken place across the country since 2014.

Thailand’s burgeoning oil palm sector

While Thailand is currently the world’s third-largest producer of palm oil, most of its palm oil is used domestically, according to Thailand’s Office of Agricultural Economics (OAE).

The country’s oil palm plantations and refineries are found mostly in the south where the climate is more suitable for cultivation. However, Krungsri Research, an analysis arm of Thailand’s Bank of Ayudhya, found the sector expanded into the country’s north, central, and northeastern regions between 2008 and 2012.

Unlike the world’s two palm oil producing giants – Malaysia and Indonesia – where large industrial plantations make up the majority of the sector, Thailand’s palm oil industry is dominated by smallholders like Chimtong, who manage over 70 per cent of the country’s approximately 700,000 hectares of plantations (as of 2015).

The growth in new plantation areas has been part of the Thai government’s strategy to boost the industry and meet the nation’s demand for alternative energy – in particular Thailand’s biodiesel industry, which has seen its consumption of domestic crude palm oil grow from 32 percent in 2009 to 45 per cent in 2015, according to OAE data analyzed by the Bank of Ayudhya.

The government’s Alternative Energy Development Plan for 2015 – 2036 includes an Oil Palm and Palm Oil Industries Development Strategy 2015 – 2026, which aims to boost palm oil production by improving yields and expanding plantation areas by 50 percent over the next nine years.

Ultimately, the strategy aims to increase cultivation of oil palm from 5 million rai (approximately 2 million acres) in 2017, to 7.5 million rai (approximately 3 million acres) in 2026.

The 2015-2026 plan also promotes the ASEAN Sustainable Palm Oil (ASPO) standard, as well as the establishment of a permanent organization to drive research and development of the country’s palm oil sector.

Expansion of land areas dedicated to growing oil palm continues to soar worldwide. In 2009, oil palm plantations accounted for approximately 10 per cent of the world’s permanent cropland, according to the Center for International Forestry Research.

With the Thai government’s policy to expand its oil palm plantations by around 50 per cent over the next nine years, it remains to be seen how the country’s tropical peatlands will fare in the coming decade.

This story was published with permission from Mongabay.com