China’s economic growth since the turn of the century has been accompanied by efforts to improve energy efficiency, leading it to become “the world heavyweight” in this area, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Energy efficiency improved by 30 per cent in China between 2000 and 2015. Industry was both the main driver of economic growth and the biggest consumer of energy during this period but recorded the largest improvements in efficiency. Brazil’s economy also recorded high annual growth rates over the same period until it entered recession in 2014. Yet, energy efficiency in Brazil has not improved.

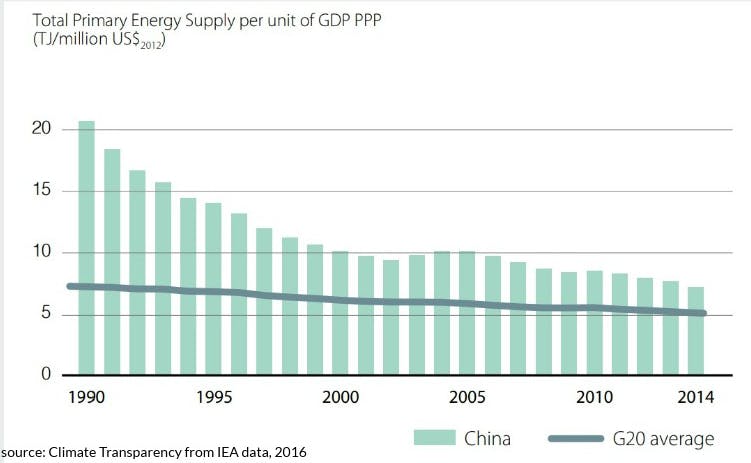

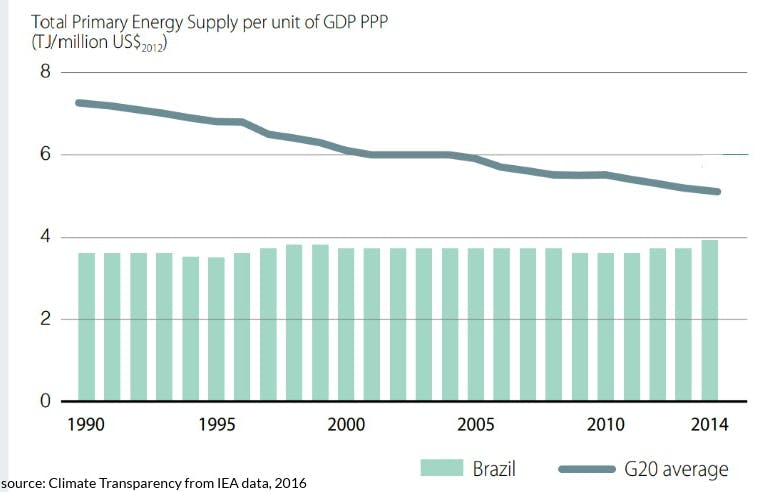

Economies tend to use more energy as they grow. However, reducing energy intensity—calculated as the amount of energy used per million US dollars of gross domestic product (GDP) generated—can lead to an eventual decoupling of energy consumption from economic growth.

In Brazil, the energy intensity of the economy has remained conspicuously unchanged since 1990, when the country used less than four terajoules of energy per US$1 million of GDP.

The research group Climate Transparency rates Brazil’s recent developments (2009-2014) as “very poor”. In contrast, China has witnessed steady improvements in its energy intensity, with recent performance rated as “very good”. These improvements are linked to centrally planned programmes designed to optimise the country’s energy efficiency that were first launched in the 1990s.

Almost 30 years ago, China required over 20 terajoules/US$1 million GDP. Today, the figure stands at around a third of that 1990 high.

The energy-intensity of China’s economy (1990-2014)

The energy-intensity of Brazil’s economy (1990-2014)

Why have these “emerging economies” had such different experiences of balancing energy efficiency with growth? A closer examination of consumption patterns in both countries, and the policies that influence them, hold important clues.

Industry is key

Industry in China accounts for around 70 per cent of total end-user energy consumption, which makes the sector critical to China’s efforts to reduce carbon emissions because 85 per cent of its energy use is derived from non-renewable sources.

As in many developing nations, combining measures to save energy and boost efficiency has been a challenge for China. In the 1980s, when energy use was particularly high in the steel, oil-refining, coking and chemical sectors, the government started building a system to improve efficiency.

Both the IEA and China’s top planning body the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), estimate that between 1990 and 2013 the G20 nations, which account for 80 per cent of primary energy consumption worldwide, saw energy intensity drop by around 1.5 per cent a year, collectively.

In Brazil, industry is followed closely by residential consumers, which represent 28 per cent (2016) of total energy consumption, according to the 2017 Statistical Annual of Electrical Energy, published by Brazil’s Energy Research Company’s (EPE), the government’s planning and research arm. Most energy saving initiatives have tended to focus on domestic consumption.

After more than two years of recession that led to an aggregate 8 per cent contraction of the economy, Brazil’s economy is now growing again, albeit slowly. Greater energy consumption looks likely to follow, especially in the industrial south-east (which accounted for the largest regional drop in energy use during the downturn). Nationally, energy consumption grew 1.3 per cent in 2017; following decreases in 2015 and 2016 of 6.2 per cent and 2.5 per cent respectively.

But as its economy recovers, Brazil could look to China as an example for how to deliver improvements in energy efficiency, according to Dai Yande, head of the NDRC’s Energy Research Institute (ERI).

While there are lessons in China’s success, many of these are closely linked to the country’s unique political and governance systems. Applied to an ambitious programme of industrial upgrading, which prioritised the development of higher value-added sectors and shifted investment away from energy-intensive heavy industries, it reveals where gains in energy efficiency can be achieved.

The third stage: from ‘managing’ to ‘promoting’

China’s system for reducing energy intensity has gone through two stages, and is currently shifting to a third, according to ERI.

The first stage was from 1981 to 1997. At the beginning of this period, China produced only one-seventh of the energy it does today. Government energy saving campaigns were intended to relieve energy shortages by planning all aspects of energy-saving in businesses.

This period saw the establishment of mechanisms for assigning and auditing energy quotas for state-owned companies, the main consumers of energy at that time. These were driven by government orders that placed strict limits on energy use by businesses. Energy use was brought under control, and reduced where possible.

The second phase started in 1997 when the Energy Conservation Law came into effect. This made the state responsible for setting energy efficiency standards. New companies were required to satisfy the standards before starting operations.

The government no longer only ordered state-owned firms to take certain energy-saving steps – all types of companies were legally required to save energy. The Central Committee, the Chinese Communist Party’s top leadership body, approved the conservation of resources as part of national policy.

The Administrative Measures for Energy Conservation in Key Energy Consumers, which were issued in 1999, provided more detailed rules to firms using more than the equivalent of 10,000 tonnes of coal for energy per year.

Companies hired “energy managers”, responsible for overseeing energy use. Only engineers with three years of experience in energy-saving work were qualified to hold the position.

The government also started to offer substantial subsidies to encourage energy-saving measures, such as the purchase of better equipment and technology. By this point, a sound system for managing energy-saving in some Chinese companies had begun to take shape.

The third, most recent phase of energy saving arrived with the new environmental focus of the 11thand 12th Five-Year Plans (FYP) for development that covered the periods of 2006-2011 and 20011-2015, respectively.

The 13th FYP period beginning 2016 continues the legacy with a special Action Plan for Energy Conservation jointly issued by 12 ministries including NDRC, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST), and the Ministry of Finance (MOF).

Toughening targets

As China’s energy-saving strategy intensified, its national energy consumption targets grew steadily more ambitious.

In 2006, a target was set to reduce energy intensity by 20 per cent over the period of the 11th FYP. This stressed the need for a more sustainable model of development. It was the first time China had set a binding energy-intensity reduction target in its national quinquennial plan and marked the start of energy-intensity controls.

Wei Han, program officer on industry at the Energy Foundation China, said that industry insiders regarded the target as a powerful signal from government promoting energy saving and emissions reductions, mitigating climate change and promoting green economic growth. The target translated into an estimated annual emissions reduction of over 1.5 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide.

But it also attracted controversy.

In a desperate late rush to meet the targets, local authorities reportedly cut power supplies to factories, traffic lights, and even hospitals. The episode also served to demonstrate how responsibility for targets was increasingly held by local officials that were accountable for their performance. In the end, China achieved an energy intensity reduction over the 11th FYP of less than one percentage point shy of the goal.

Under conditions of rapid economic growth an energy intensity target may not prevent growth in overall energy consumption. To achieve this, the Chinese government added a total energy consumption target in 2016 to existing intensity targets, saying that “2020 total energy consumption will be within 5 billion tonnes of coal equivalent.”

This story was originally published by Chinadialogue under a Creative Commons’ License. Read the full story.