Think of a research laboratory and pristine bare rooms lit by fluorescent lights come to mind. What doesn’t is that a lab can consume up to 100 times as much as energy as a similar sized office.

Behind this mind-boggling figure are power guzzling laboratory equipment and, more critically, the need for high-end ventilation systems.

Due to safety requirements, a laboratory needs up to six or 12 air changes per hour—the number of times the air in a room is renewed by exchanging it with outside air—compared to the single air change per hour in an office, according to the International Institute for Sustainable Laboratories (I2SL), a global body focusing on improving safety and sustainability in laboratories.

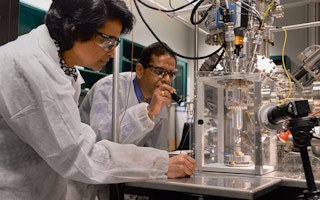

Intuitively, this makes sense; in a confined area, working with materials and setups that can be volatile, toxic, highly sensitive to the environment, or any combination of the three, good ventilation is key to protect the health of researchers working there. Energy-intensive mechanical ventilation, which uses ducts and fans to circulate fresh air into the laboratory, is necessary.

But that huge power sink, according to I2SL executive vice president Gordon Sharp, is also the low-hanging fruit when it comes to making laboratories more energy efficient.

“It all comes down to air flow—that’s the core driver for energy use in laboratories,” he said, speaking in Singapore for the Siemens Labs Innovation Day in August. In contrast, many common solutions to reduce a building’s emissions output, such as designing for natural ventilation and lighting, raising air conditioning temperatures, or adding greenery, simply do not work with safety regulations.

“Laboratories require a very clean and tightly controlled environment,” said Sharp, who is also the chairman of specialist ventilation firm Aircuity. “The top concerns are safety, security, and regulatory compliance—natural ventilation is not adequate, and you can’t have plants in that environment either.”

While speakers at the event spoke about solutions including heat recycling and chilled beams to bring down the energy footprint of laboratories, the area of ventilation was where they said the quickest gains could be made for sustainability.

Smart ventilation for sustainable labs?

Ensuring a sensitive workspace like the laboratory has proper ventilation is crucial, but the truth is such a high level of air flow is only required when the space is in use. And even then, the highest rates of air flow are only required when personnel are working with hazardous materials, Sharp said.

If air flow can be raised and lowered as needed, the energy consumption needed for ventilation could be significantly reduced, to the point where a laboratory can operate with just two air changes per hour on the average, he adds.

Digital demand-based control systems, which monitor air quality and reduce air flow if the air in the laboratory is “clean”, or increase it if contaminants are detected, are therefore one solution to laboratories’ air flow problem. Figures from I2SL estimate that demand-based control in laboratories can cut the energy used for ventilation by 40 to 70 per cent.

And while efforts to make laboratories sustainable have been going on for over two decades, it is only within the last five years that smart infrastructure and artificial intelligence technologies have enabled energy efficiency systems like demand-based controls for air flow to be automated in response to occupant behaviour.

“The technological solutions we create are a support to behaviour,” said life science expert Tim Walsh, who is part of Siemens’ global life science portfolio team. “It allows functions like adjusting the air conditioning and air flow, monitoring the status of equipment like fume hoods, and even dimming the lights to take place without human intervention.”

For example, readings from multiple different systems—security systems, motion detectors, and air quality sensors—can be combined to accurately regulate air flow within a laboratory without affecting safety considerations.

It is now possible to detect when someone is working with hazardous materials under a fume hood (a type of enclosed cabinet with its own localised ventilation system, which contains fumes and vapours and channels them directly out of the building so that they do not contaminate the laboratory), and speed up the ventilation accordingly.

Intelligent building technology can also regulate air flow if people are present but not handling hazardous materials; or automatically close the fume hood and moderate air flow yet again if there is no one in the room; and even pre-emptively raise the air flow again when someone is about to enter the laboratory.

If this seems oriented as much towards convenience as safety, that is because, when it comes to sustainability, changing people’s behaviour can be difficult. Scientists are no exception.

“Part of the issue is that scientists become very focused on their work,” said I2SL’s Sharp. “Sometimes they have a lot on their minds, and energy efficiency slips through the cracks. It helps if we can create a situation where technology becomes invisible and the energy savings happen behind the scenes.”

This is not to say that technology is the only answer—simply that the smart solutions available today are increasingly effective at catching the slips people make.

“At the end of the day, even the most sophisticated system will take time to recognise that the room is not occupied or that the sash of the fume hood is open,” said Walsh. “I would see it as a backup: educating people is always going to be the first priority.”