A recent restructure of global not-for-profit CDP was not designed to see power shift away from Asia Pacific – a region that has been growing in strategic importance – but to ensure that APAC staff are given global functional roles that can help CDP “lean into” where it needs to be, explained Nikki Bartlett, its chief impact officer.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

“We have seen an extraordinary shift in Asia, with a big increase in disclosures as well as how well companies are performing. We are taking a lockstep approach, focusing on how the organisation can work together globally, rather than in pockets,” Bartlett told Eco-Business.

News of CDP’s restructure emerged in February, five months after the appointment of its new chief executive. Regional positions have been scrapped in favour of global functional roles, a move that prompted numerous senior sustainability executives in Asia and elsewhere to leave, and a new framework is being introduced to streamline the disclosure process. Critics say the restructure has taken power away from the regions and concentrated it in the West, since most of the global roles have now gone to West-based executives.

“Disclosure on its own does not drive action. You need a system of carrots and sticks to do that,” says CDP’s head of impact Nikki Bartlett. Image: CDP

Bartlett told Eco-Business that CDP’s new global focus was never intended to move the centre of gravity back to London, CDP’s headquarters, and numerous global roles could still go to people based in other regions. “We are only in the first phase [of the restructure],” she added. “Are we finished yet? No. Is it perfect yet? I’ll never be the first to say so. There is work to be done.”

CDP, an organisation with about 700 staff, has its disclosure function partly run out of Beijing, China’s capital city, by co-director Li Fei, Bartlett pointed out. Sherry Madera, CDP’s chief executive officer, who was previously an adviser for the Cyberport innovation hub in Hong Kong, also has a strong Asia background, she argued. CDP is transforming into a “globally run machine” with disciplines that could be run out of anywhere, she said.

CDP’s restructure follows its separation from Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi), a standards body for validating net-zero targets in line with climate science which CDP co-founded in 2015. Bartlett said regulations such as the United States Securities and Exchange Commission’s recent mandate for climate disclosure are affecting companies and their supply chains all over the world, and with CDP becoming more globally-focused, it can serve regulators and companies better, “so that their dollars can be spent on action – and we can track that action in a transparent way.”

“There’s so much opportunity in what regulators are trying to do right now, but these new rules have unintended consequences – because regulators are not pulling in the same direction,” she said.

CDP is working on a new framework that it aims to bring more standardisation to the plethora of environmental disclosure rules around the world. “It is vital that you get a very structured, consistent, comparable dataset. And that dataset can be used by companies, investors, and even regulators, to make better decisions,” she said.

The potential that Asia holds to help bend the curve is exciting. Is Asia near a tipping point? Maybe. Because there is a lot of business value to be derived from being a sustainable company.

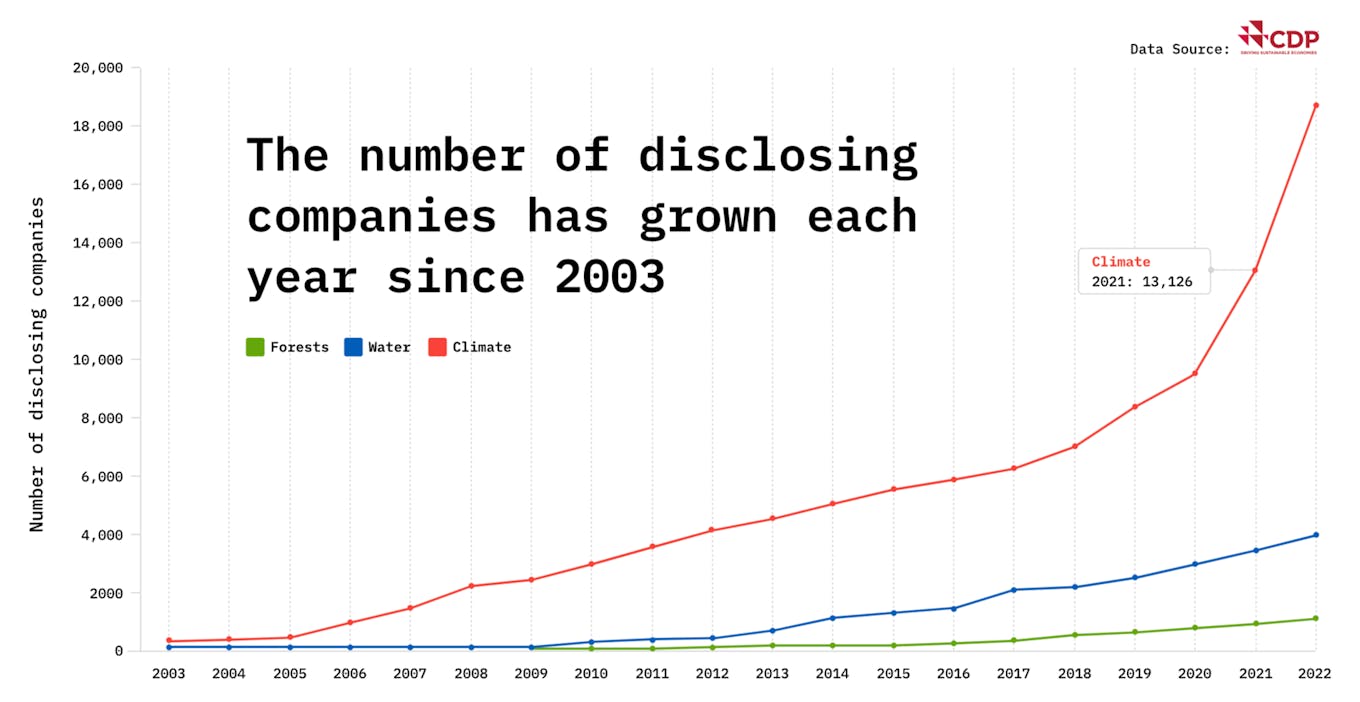

Founded in 2000 as Carbon Disclosure Project, more than 23,000 firms reported their environmental impact through CDP in 2023, a year-on-year increase of 24 per cent – and a 300 per cent increase since the Paris Agreement of 2015. In Asia, the number of companies reporting their environmental footprint has grown by 172 per cent since 2020 and it is second only to Europe as the fastest growing region for disclosure.

In this interview, Bartlett explains the thinking behind the restructure at CDP, how shifting supply chains are affecting corporate climate action in Asia, and why global emissions are not falling despite huge increases in environmental reporting.

Why is CDP restructuring?

As regulations emerge which are not aligned globally, multinational companies are facing a plethora of reporting requirements – and that means less money they can spend on taking action.

We want to be able to make sure that regulation is driving decision-making in the right direction. So there was a need for our organisation to be globally-focused and double-down on the action we need to see in the economy. Because we know that measurement and transparency drives action.

The more globally focused we are, the more we can serve regulators and companies by creating a much more efficient measurement and reporting world for them, so that their dollars can be spent on action – and we can track that action in a transparent way.

Regulators do care that the information in the system is real, and that it’s getting better and more efficient. We want to make sure that our system can help identify the gaps as industry moves towards standardised data.

Underneath all the different regulations are the standards for measurement, like the Greenhouse Gas Protocol – and that hasn’t been standardised yet. Regulation helps with the standardisation process. We are now in the place where we want to take the best of regulation and make it bear fruit as fast as possible.

Now that we have more data coming into the space, we want to make sure that it’s a comparable and standardised dataset that covers what science needs it to cover, and that it is being used to drive change in the system.

Why does the framework companies use to disclosure their environmental impacts need updating?

In the previous way of working, there were challenges that were unique to, say, Singapore or India. One of the biggest challenges was SME [small and medium-sized enterprises] disclosure. What Europe defines as an SME is a listed company in Singapore, for example. We were struggling as an organisation to all pull in one direction and frame SME disclosure in a way that worked for SMEs everywhere.

With the new framework, a reframed questionnaire, and a whole new platform, we have done that. It’s designed to tackle some of the unique issues that Asian companies are grappling with, as opposed to just what European companies are grappling with.

Take us through how CDP is restructuring.

CDP is a global organisation – and is becoming even more global. We pivoted from being a founder-led organisation into an interim structure while the new CEO was searched for. The CDP trustees were obsessed with finding the right person. We now have Sherry Madera as CEO [formerly of credit card firm MasterCard and data company Refinitiv, who succeeded co-founder Paul Simpson and replaced interim CEO Jamie Neil].

Our new CEO has a strong Asia background [Madera was previously an advisor for the Cyberport innovation hub in Hong Kong] – and that was very deliberate. The restructure was designed so that we can all pull in one direction and lean in to where we need to be. And right now, the place we need to lean into is Asia Pacific.

We have seen an extraordinary shift in Asia, with a big increase in disclosures as well as how well companies are performing. We are taking a lockstep approach, focusing on how the organisation can work together globally, rather than in pockets. For instance, our disclosure team is co-led by someone in Berlin [David Lammers] and in Beijing [Li Fei].

We’ve found that it’s much smarter to run as a globally set up machine. A whole bunch of global roles were opened up for the first time across the system. The aim is to get away from the notion that we have regional offices. We’re all one machine, with one strategy.

Increases in CDP disclosure over the years. Source: CDP

Despite the huge increases in disclosure from industry, global greenhouse gas emissions are still rising. When are we going to see a rise in corporate climate action correspond with a drop in emissions?

First, think about where the world would have been on its current growth curve and where it is now, thanks to policy, decarbonisation and clean energy growth. We would have been in a much worse place.

Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is cumulative and long-lived in nature. Cumulative growth is all that matters to the atmosphere, whereas from an economist’s perspective, the relative change to the economy [from decarbonising corporates] has been quite fundamental.

Recent International Energy Agency figures [released early March] showed that clean growth has gone crazy, but we still haven’t bent the curve on emissions [the IEA concluded that without clean energy technologies, the global increase in emissions would have been three times larger over the past five years].

This is because economies are still growing and new clean energy is essentially adding to an energy load that didn’t exist before – because there was an energy deficit. And the world has not reached ‘peak energy’ yet.

Disclosure on its own does not drive action. You need a system of carrots and sticks to do that. And I think we’re only just starting to scratch the surface of some of those tipping points. I think we’re reached a tipping point for the energy sector – but we haven’t got there yet for heavy industry or transport.

On one level, the climate community has done way better than I ever thought we would. But on another level, we’re not even close where we need to be.

Looking across the CDP system, it used to be a common refrain from my Asian colleagues to say: “Progress is all well and good, but it’s European companies doing these things [disclosing and decarbonisation] – you can’t expect that from Asian companies.” That just does not hold hold water anymore.

It’s always been very irritating for different parts of the world that we use the same benchmarks and methodology for companies everywhere. But now, in the most recent CDP A-List scores, 40 per cent of companies graded ‘A’ were from Asia.

It usually takes a minimum of three years for a company in CDP’s system to move up the grade curve. In Asia, that progression is much faster at the moment. That’s really heartening – because Asia is the region with the fastest growing missions, but is also the region with the fastest rate of change. We even saw a jump in disclosures from Cambodia and Vietnam this year – and that’s probably because supply chains have shifted [away from China towards Southeast Asia].

What else have you noticed from the CDP scores this year?

Supply chains have been one of the most powerful drivers in the CDP system for over 10 years. There are a variety of reasons for that.

One is that a client really matters to a business. Companies are making procurement decisions using sustainability criteria. Companies do not want to lose their supply chains – as we saw during the Covid-19 pandemic – so they’re starting to incentivise [carbon reductions] at scale. It’s a very direct feedback loop.

Another is access to capital, which can be quite nebulous and indirect, particularly for equity.

What’s happening now is that the access to capital and the supply chain drivers are coming into the system at the same time. That really matters, particularly to SMEs. That is really important in Asia [where the vast majority of firms are SMEs that are part of global supply chains].

There are a few trends at play here.

First, it used to be the case of what was described in China as the “outside in” strategy, where multinationals based in Europe or the US had their supply chains in China. It was a big driver of change in the region.

Now, we’re starting to see supply chains that just cover Asia, with Chinese companies using Southeast Asia as their supply chain.

Companies focused on their supply chains are now Asian multinationals as much as they are European or US multinationals – and that is causing a scale-up [of disclosures] all across the region.

Second, we’re seeing a shift in supply chains among US and European companies out of China and into Southeast Asia.

Those two things together are driving a sort of Southeast Asian revolution [in corporate climate action].

The interesting thing is that it’s causing a bunch of companies to recognise that they have the same challenges and can solve all of those challenges together.

So, yes, the emissions curve has not gone down. But the potential that Asia holds to help bend the curve is exciting.

Is Asia near a tipping point? Maybe. Because there is a lot of business value to be derived from being a sustainable company. From a climate perspective, the short-term trade-offs in some sectors are not looking as stark as they used to look.

Regulation, particularly from Europe with the EU Deforestation Regulation, is starting to drive change among companies in this region. How do you see this playing out?

Climate action is not a first-mover advantage anymore – it’s a do or die.

I do find it heartening that a regulator has the balls to regulate like this. The boldness of the EU around some of these issues is having a ripple effect globally, because they have focused on supply chains.

But I do find it very sad that there has been such pushback against the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive [or CSDDD, which was provisionally agreed in December 2023, to curb corporate abuses on human rights and the environment, but was not agreed upon by EU member states].

[The CSDDD] obliges European-headquartered companies to guarantee that they don’t have human rights abuses and environmental damage in their supply chains. That’s one hell of an ask, but it’s also a hell of a thing to think that’s one hell of an ask. That shows you how big the battle is that we have to fight.

Can you tell us why a company like tobacco giant Philip Morris scores ‘A’ for climate, water and nature in CDP’s scores? What value do they really add to the planet?

We’re an environmental organisation that benchmarks companies on environmental leadership. We don’t take a social approach to that benchmark.

Does that mean we think tobacco companies are adding to society? That’s not for us to say. We’re neutral and we focus on the ‘E’ [in environmental, social and governance].

In our scoring methodology, Philip Morris is very transparent and committed, and has invested to drive down land use and biodiversity impacts and shown leadership on water security. It’s there. It’s all in the data.

We’re very clear about what our scoring methodology is about and what it’s not about. It is not an endorsement from CDP of one company or another company’s product or service.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.