Some 400,000 solar panels, spread over 200 hectares of flat desert, glare defiantly at the sun at what is known as the Quaid-e-Azam Solar Power Park (QASP) in Punjab, named after Pakistan’s founding father.

The 100 MW photovoltaic (PV) solar farm was built by Chinese company Xinjiang SunOasis in just three months, at a cost of around US$131 million and started selling electricity to the national grid in August.

This is the first energy project under the US $46 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, a key part of China’s ‘new silk roads’, linking the port at Gwadar in southern Pakistan with Kashgar in China’s western region of Xinjiang.

The 100 MW plant is the pilot stage of a more ambitious plan to build the world’s largest solar farm. Once completed in 2017, the site could have capacity of 5.2 million PV cells producing as much as 1,000 MW of electricity – equivalent to an average sized coal-fired power station and enough to power about 320,000 households. Construction of the next stage is already underway, led by Zonergy, another Chinese company.

Eighteen months ago, the site was nothing more than wilderness. Now a mini city has emerged in the middle of the desert, with over 2,000 workers accompanied by heavy machinery, power transmission lines, blocks of buildings, water pipes and pylons.

Reducing emissions, providing livelihoods

The Cholistan desert is the ideal spot for solar power, said Muhammad Hassan Askari, operating manager of the solar park. The area gets 13 hours of sunlight every day while the huge expanse of flat desert is ideal for a large commercial project.

The big advantage of solar power, he said, is that a large park can be completed faster than thermal or hydropower projects, which take much longer and require a lot of maintenance.

“

It may have been better to build the equivalent remaining 900 MW closer to where electricity is consumed – on say the rooftops of large parking lots – rather than installing it in remote locations.

Ali Hassan Habib, former director general of WWF-Pakistan

The solar park will also shrink Pakistan’s carbon footprint, said Najam Ahmed Shah, the chief executive officer of QASP, displacing about 57,500 tonnes of coal burn and reducing emissions by 90,750 tonnes every year.

Pakistan aims to reduce its reliance on hydrocarbons, especially imported coal, oil and gas, to around 60 per cent by 2025 from the present 87 per cent. The country has a target to produce 10 per cent of its total energy mix from renewables (excluding hydropower, which already constitutes 15 per cent of the total energy mix). The current generation from renewable energy is around 1-2 per cent.

While Pakistan contributes less than 1 per cent to global GHG output, the country’s carbon emissions are growing by 3.9 per cent a year. By 2020 it will spew out 650 million tonnes of CO2e (carbon dioxide equivalent) if the current trend continues, said climatologist Qamar-uz-Zaman Chaudhry, the UN secretary general’s special advisor for Asia with the World Meteorological Organisation.

The solar park will also eventually generate 15,000 to 33,000 jobs for local people alone and attract investment to the region.

Unprecedented scale

Some experts worry the project is too ambitious. Former director general of WWF-Pakistan Ali Hassan Habib, who now runs a company providing rooftop solar solutions, welcomed the project but was uneasy about the government “jumping into untested scale”. The plant will be almost double the size of the existing largest solar PV generating facilities worldwide, he said.

“It may have been better to build the equivalent remaining 900 MW closer to where electricity is consumed – on say the rooftops of large parking lots – rather than installing it in remote locations,” he said.

Environmental impact of clean energy

Because solar energy is still finding a foothold in the energy mix and technologies are evolving, not enough is known about the park’s impact on the environment and natural resources.

Infograph: thethirdpole.net

Some negative impacts have already become apparent. For example, solar power consumes lots of water. PV panels may require little maintenance, according to QASP, but they need to be kept squeaky clean. An estimated one litre of water is used to clean each panel. Water consumed to clean the eventual 5.2 million panels built will be colossal for a country that is fast becoming water stressed. Currently, 30 people take 10 to 15 days to clean the entire 400,000 cells.

“This year we’ve been very lucky as there have been unprecedented rains and so panels were cleaned automatically,” said Askari, who said they were looking for more efficient ways to clean panels.

At the same time, increasing human activities will disturb the arid region’s rich biodiversity and wildlife, such as the chinkara (Indian gazelle), caracal cat and houbara bustard.

The construction of new road network and supporting commercial activities associated with large solar PV projects do leave a substantial “footprint” on the land, agreed Habib.

Shah justified the project, saying it was built on uninhabited wasteland. “An Initial Environmental Examination was carried out and we got a nod from the Environment Protection Department before embarking upon the project,” he explained.

Habib suggested the government set up an environment and social fund to offset any negative impact.

Environmentalists are also concerned about the fate of the millions of PV panels which will wear out within 25 years. The panels will have to be recycled to extract the silicon used to make them, and then replaced.

Pakistan’s energy crisis

Pakistan has been in the grip of severe energy shortages for many years with some rural areas left without power for up to 20 hours a day. There has been little local or foreign investment in the industrial sector because of the extensive power cuts, and a number of factories have had to close down.

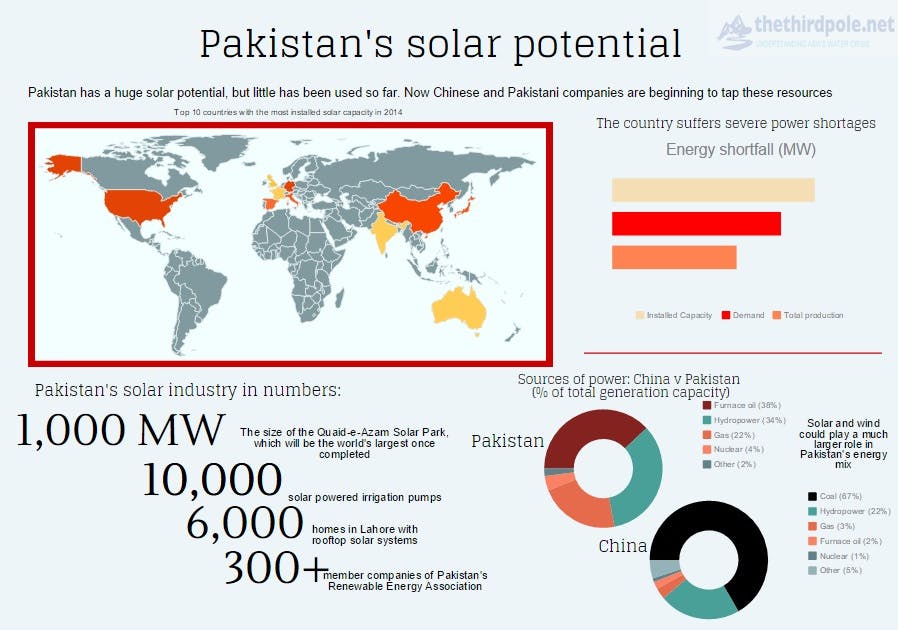

With an installed electricity generation capacity of 22,797 MW, the country’s total production stands at just 14,000 MW. In recent years, demand has risen to 19,000 MW.

While the 1,000 MW of solar energy will help ease energy constraints, Askari said government investment in several other hydropower and coal projects should also help alleviate power shortages.

Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif promised power cuts would end by 2017-2018 at the inauguration ceremony of 100 MW solar project in May, earlier this year.

Not everyone is happy

But some critics say it is the investors who will get rich from the solar project, while consumers will have to pay more in the long run.

“Hydropower can produce energy for less than half the price of solar and about the same as wind so why a fixation on solar?” said an Islamabad-based energy expert working with the government, who spoke to thethirdpole.net on the condition of anonymity.

He is sceptical of solar for a number of reasons.

First, the solar farm will actually produce far less than the much touted 1,000 MW of electricity. “On average, solar power plants deliver only about 20 per cent of installed capacity, and the peak production is during the day, while the peak demand is in the evening when the plant does not produce anything,” the expert pointed out. Alternative arrangements have to be made to draw upon hydro or thermal sources at an “extra cost”. But the project’s owners say the 100MW solar plant could produce near to capacity at 85MW at its peak.

Second, solar energy is more expensive than other energy sources. QASP claims it is selling solar power to the grid at US$0.14/unit. Sources within theNational Transmission and Despatch Company say they have signed a deal to buy electricity at $0.24/unit, which will drop later to perhaps $0.17/unit after seven years when loans are paid off. In either case, this price is far higher than the $0.07 for hydropower, $0.11 for fuel oil and $0.12 for imported LNG.

“And these figures are only for generation; another 25 per cent must be added to it for cost of delivery to be borne by the consumer, accounting for losses and theft,” he pointed out.

“The financial justification for solar was approved when oil prices were at US$110 a barrel,” he said, lamenting that the government refused to heed to advice that oil prices would drop.

Others argue that solar prices will decline over time, making it competitive. Vaqar Ahmed, deputy executive director at the Islamabad-based think tank, Sustainable Development Policy Institute, said: “For every new technology the fixed costs are higher in the initial years and diminish over time as economies of scale are achieved.” And learning from China, efficiency will rise and prices for solar cells will continue to fall, he said.

Wind could be a much bigger contributor to Pakistan’s energy need, said WWF’s Habib, given its potential of 120,000 MW. “Unlike solar, wind energy maintains production at night,” he pointed out.

Political risks

With just a little over two years left in his term, the success of the solar project is important for Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif.

“The project has huge political implications for the ruling Pakistan Muslim League (N),” said Lieutenant Colonel (Retired) M. Hassan Malik, who is responsible for the security arrangements of the entire QASP area.

“Through this project the government also wants to send out the message to the outside world that it has the capacity to undertake mega projects and will provide foolproof security to investors.”

Working in an area characterised by lawlessness and extremism, Malik’s job is challenging. “Not only is the park a national asset, we have foreign nationals working at the plant, so the sensitivity is two-fold,” he said.

There are 800 to 900 men guarding the site where around 400 Chinese workers and over 2,000 labourers work at any given time.

Culture shock

For Alexander Halbich, a German engineer who has been at the park for over a year, getting used to heavily armed security men following him around was most disconcerting aspect of his new job. “The food is good, the people are extremely hospitable and we do go out to the city once in a while tailed by armed guards, but there is little to do after dark,” he added.

“There isn’t much to do in the evenings,” agreed Muhammad Hasan Askari, who heads the technical team. Hailing from Lahore, Punjab’s capital, he keeps himself busy with work and looks forward to going home at the weekends.

Foreign workers get to go home less often. “I go every three months for ten days or more,” said Zhang Ting, a young Chinese engineer. “I’m quite ready to go home by two months but when I do go back, I miss Pakistan and the work,” she added.

Ting had to deal with a language barrier and hostile weather when she arrived to work at the site. The Chinese engineer also had to adjust to a very different work culture.

“We resolved the issue by getting more Pakistanis on our design team to crease out the differences and conflicts,” she said.