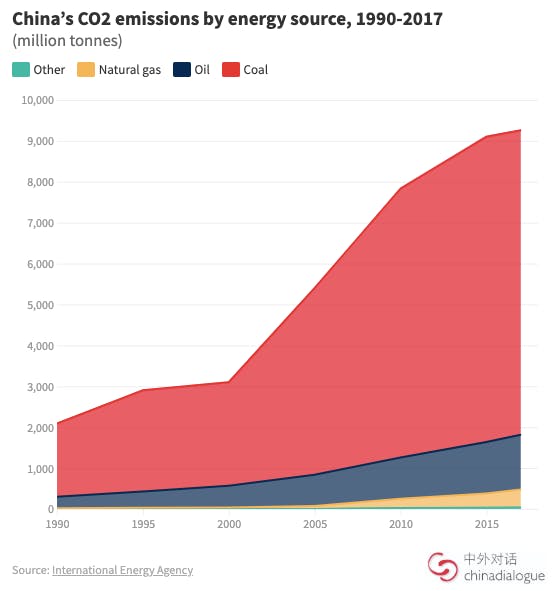

The major emitters of greenhouse gases are critical to getting the world on track to manage global warming. In 2014, China announced its carbon emissions would peak around 2030. Despite rising slightly in 2017 and 2018, the country’s coal consumption has fallen overall since then.

But what of oil? What are the prospects of the world’s second largest consumer and biggest importer peaking its consumption?

A two-year study led by the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC), an environmental non-profit, has concluded that China must “leap over the oil age” to meet its various targets – to ensure energy security, protect the environment and public health, and meet the climate challenge.

Carbon peak, five years early

As countries develop, the main fuel in their energy mix tends to move from coal to oil to renewables. But the NRDC-led report found that tightening resource, environmental and climate constraints mean China must skip the oil stage and find an innovative “oil-free route”, consuming less oil per capita than the global average.

The report, which involved China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment, Ministry of Water Resources, and National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), analysed how developed nations have reached peak oil and then considered China’s future consumption in three scenarios – under current policies; with strengthened policies; and with policies that align with the Paris Agreement target of keeping warming well below 2°C.

To reduce oil use, the report focusses on lowering demand, improving efficiency and substituting oil with alternatives. These are its main recommendations by sector:

Transport: encourage use of new energy vehicles; improve fuel economy; substitute road freight for rail and shipping

Plastics: reduce exports of oil-intensive products; restrict and ban production and use of general plastics replace oil feedstocks with biomass or natural gas

Other sectors: impose stricter energy efficiency standards; phase out old industrial equipment; shift to cleaner fuels

Under the strengthened policy scenario, China could see peak oil by 2025 (at annual consumption of 720 million tonnes), which would then fall to below 420 million in 2050 (350 million tonnes lower than in the current scenario). This would also mean achieving peak carbon in 2025, five years earlier than the 2030 target China committed to under the Paris Agreement.

Transport is crucial

Han Wenke, former head of the NDRC’s Energy Research Institute, said at the release of the report that the institute had reached similar projections for the 14th Five Year Plan period: cutting consumption could save 200 million tonnes of oil a year, with the reductions being realised between 2030 and 2035. “We need to work hard to reduce oil consumption right now. But even if we do, the results will only be seen over time.”

During the 13th Five Year Plan (2016-2020), China started controlling both total energy consumption and energy intensity, aiming for a 15 per cent fall in energy use per unit of GDP over the five years, and to keep total energy consumption within the equivalent of five billion tonnes of coal. Han suggested that “more precise control of fossil fuel consumption [by fuel type]” be put in place during the 14th FYP.

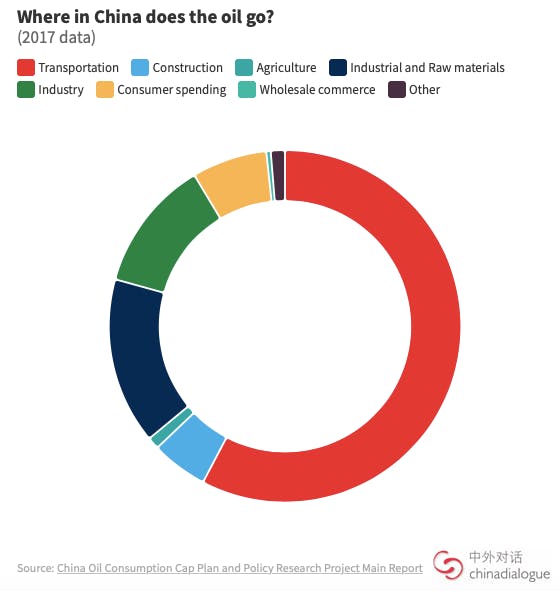

Action in the transport sector, which accounted for 58 per cent of China’s oil use in 2017, will be essential. The report points out that new energy vehicles (NEVs) and alternative fuels such as biofuels will be of most benefit to reining in oil consumption, with increases in fuel economy coming second.

Development of NEVs (which includes all-electric, hybrids and fuel cells) is speeding up. Conservative predictions see NEVs passing 40 per cent market penetration in China by 2050. Although there may be some obstacles – such as higher prices caused by subsidies being cut, or infrastructure failing to keep up – the government is continuing to put policies in place designed to promote the sector. In 2017, the head of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology indicated that China was looking at a gradual phase-out of fuel-burning vehicles.

Reducing oil consumption via better fuel economy is tougher, with the fondness of Chinese drivers for SUVs set to be a particular problem. A conventional SUV burns 25 per cent more fuel than a medium-sized car, and a recent report from the International Energy Agency says a preference for SUVs may offset the emissions savings from electric vehicles. SUV carbon emissions increased by 100 million tonnes from 2010 to 2018, the equivalent to annual emissions from 25.7 coal-fired power plants, and SUVs are contributing more to emissions growth than the road freight sector.

Ten years ago there were only three million SUVs on China’s roads. Now there are more than 50 million. Of every 10 vehicles on China’s roads, four are SUVs.

As they are bigger and heavier than an ordinary car, electric SUVs require more batteries, making electrification harder. Internationally, half as many SUVs are electric as non-SUVs – and the rate is even lower in China. According to the China Passenger Car Association, only 280,000 of the 1.1 million electric vehicles sold in China in 2018 were SUVs.

Less plastic, less oil

Currently, the fastest growth in oil consumption is seen in the petrochemical industry, which accounted for 15.3 per cent of total use in 2017. The report pointed out that as more refining capacity comes online in China in the future, the petrochemical industry will become a new driver of oil demand.

Yang Fuqiang, the NRDC’s senior adviser on energy and climate, said reductions in oil use in transportation will be cancelled out by more use in the petrochemical industry. In future, more oil will be used in the chemical industry than as a fuel; notably, to make plastic.

In 2008, China banned supermarkets from providing free single-use plastic bags, but enforcement has been weak and charges for bags too low to put consumers off. Last month, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment and the NDRC announced a ban on plastic bags in all cities and towns by 2022. Restaurants must reduce single-use plastics by 30 per cent.

Recycling rates for used plastics remain low. China produces 68 million tonnes of waste plastic every year. Only 20 per cent of the plastic used in China in 2017 was recycled, according to figures from the China Association of Circular Economy.

Zhu Kuan, manager of Shanghai Re-Mall Environmental Protection New Material, says newly manufactured plastics are still cheap because environmental costs are not factored in. As soon as the government changes that, growth in the sector will “be much less easy”.

He also thinks that the better recycling rates called for in the report will only happen when there is a demand for cheap materials. Growth in the petrochemical industry means the cost of raw materials are at a historic low, so firms see no need to recycle. Government intervention is needed to identify who is responsible for dealing with waste plastic and to make consumption more sustainable.

The new government restrictions on plastics manufacturing and use mean some parts of China will ban or restrict single-use bags, tableware and packaging by the end of 2020, and promote the use of non-plastic or biodegradable alternatives. Breaches will result in a loss of social credit. On the other hand, there will be support given to new recycling facilities.

Don’t overlook exports

Xu Jiangfeng, of the China National Offshore Oil Corporation, pointed out that China has excess refining capacity, some of which is used to refine imported crude oil for export. “What we’re doing,” Xu said, “is using our air, water and soil to meet the needs of our excess refining capacity and the overseas markets.”

According to the customs authorities, 13 million tonnes of petrol and 20 million tonnes of diesel were exported in 2018, up 23 per cent and 8 per cent on 2017 respectively.

With refining capacity rocketing, China has an oversupply of refined products like petrol and diesel, and the industry regards increased exports as a solution. Liu Qiang, of the Chinese Academy of Social Science, says that demand for refined products needs to be reduced, both for energy security and to reduce pollution.

This story originally published by Chinadialogue under a Creative Commons’ License.