Though the post-pandemic reopening of the world’s economy is often considered a positive development, some of the largest and most recognisable tech companies are struggling to adapt to the changing circumstances.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Earlier this month, Meta, the parent company of social media site Facebook, announced its first mass layoff since the company’s inception 18 years ago. Thirteen per cent of its workforce, or more than 11,000 employees were affected, including at least 50 workers at its Asia-Pacific headquarters in Singapore. Though the proportion of business and technology positions affected were relatively similar at 54 and 46 per cent respectively, some departments like recruiting were worse hit than others, with nearly half of the team made redundant.

Regional giants like Sea Limited, the parent company of e-commerce site Shopee, have also struggled to remain profitable. In addition to rescinding job offers and pulling out of markets in India, France and Spain, the company also initiated three rounds of cuts in June, September and earlier this November, affecting more than 7,000 employees, or around 10 per cent of its workforce in total.

Yesterday, Singapore’s Minister for Manpower Tan See Leng reported that there were 1,270 resident workers laid off from tech companies from July to mid-November this year, nearly five times the number retrenched during the first six months of the year. Of the 1,270 workers, 8 out of 10 were in non-tech roles like sales and marketing, and 7 out of 10 were 35 years or below.

“

Climate is going to have a transformational impact on sectors that add up to more than 50 per cent of the world’s GDP.

Nishant Mani, chief business officer, Terra.do

As lockdowns drove up demand for online services and lower interest rates made loans more affordable, many tech companies chose to expand their operations rapidly. However, because of the ongoing Ukraine war’s effect on global energy and commodity prices, United States consumer prices have risen 8.6 per cent year on year and the US Federal Reserve has hiked interest rates three times this year alone, with the latest increase being the largest since 1994. As a result, many tech companies were unable to service their debt and had to lay off the excess workers they accrued during the pandemic to stay afloat.

In a memo issued on 9 November, Meta co-founder and CEO Mark Zuckerburg confirmed: “Not only has online commerce returned to prior trends, but the macroeconomic downturn, increased competition, and ads signal loss has caused our revenue to be much lower than I’d expected. I got this wrong, and I take responsibility for that.”

However, many tech profesisonals have also spoken out about the way they were treated during the retrenchment process. A week following Tesla and SpaceX CEO Elon Musk’s acquisition of Twitter on 27 October, the micro-blogging platform laid off half of its global workforce, often without any advance warning. This exodus worsened after Musk cut subsidised meals, hybrid working options and demanded employees work 84-hour work weeks.

In media reports under the condition of anonymity, ex-employees were quoted as saying, “I really don’t think that this is the way to handle a transition. I understand [that] with new management [and] new leadership, they would want change. But they’re really not thinking about the thousands of employees [working] globally at all. There’s zero empathy, which is far cry from how Twitter used to be.”

How climate tech stacks up

However, the climate tech industry has seemingly defied these downward trends, though not without shortcomings of its own. According to a PwC report published this month, early stage funding for climate tech startups has declined and investment in climate tech has not been proportional to rising greenhouse gas emissions. However, investment in climate tech this year continues to hover near last year’s historic highs, and climate tech accounted for more than a quarter of every venture capital dollar invested in the latest quarter, which is higher than 12 out of 16 previous quarters.

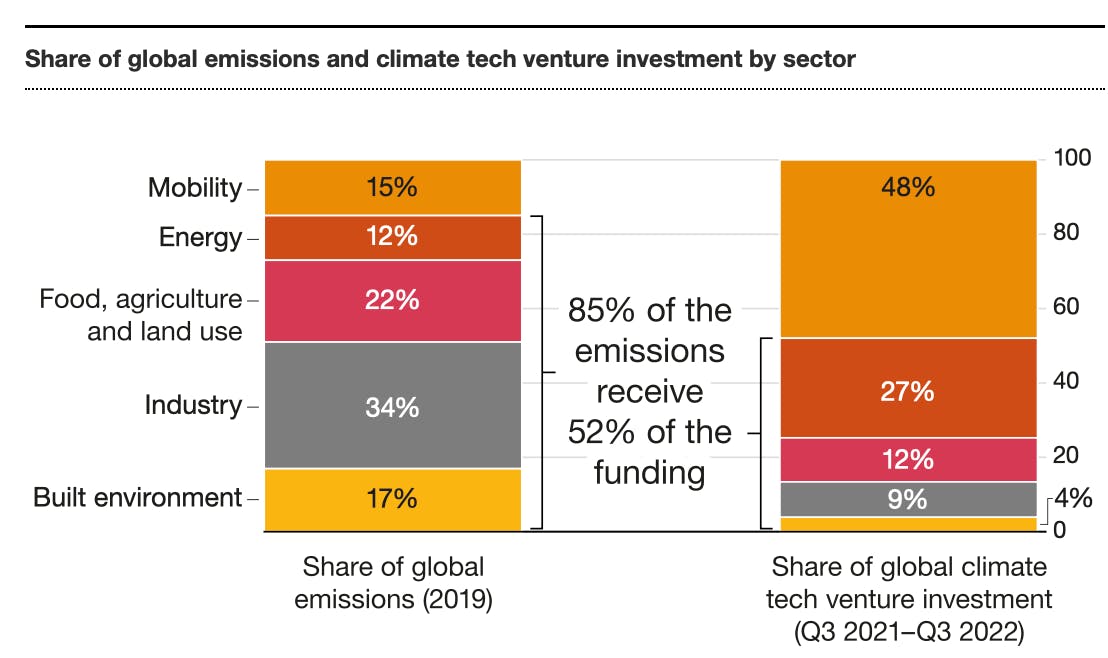

In the past 12 months, the global rate of decarbonisation was 14.7 per cent short of level needed to reach the 1.5°C climate goal. This is partly because investments in climate tech have not been proportional to the greenhouse gases emitted. For example, the mobility and industry sectors cause 15 per cent and 34 per cent of emissions, but get 48 and 9 per cent of funding, respectively. Image: PwC State of Climate Tech report 2022.

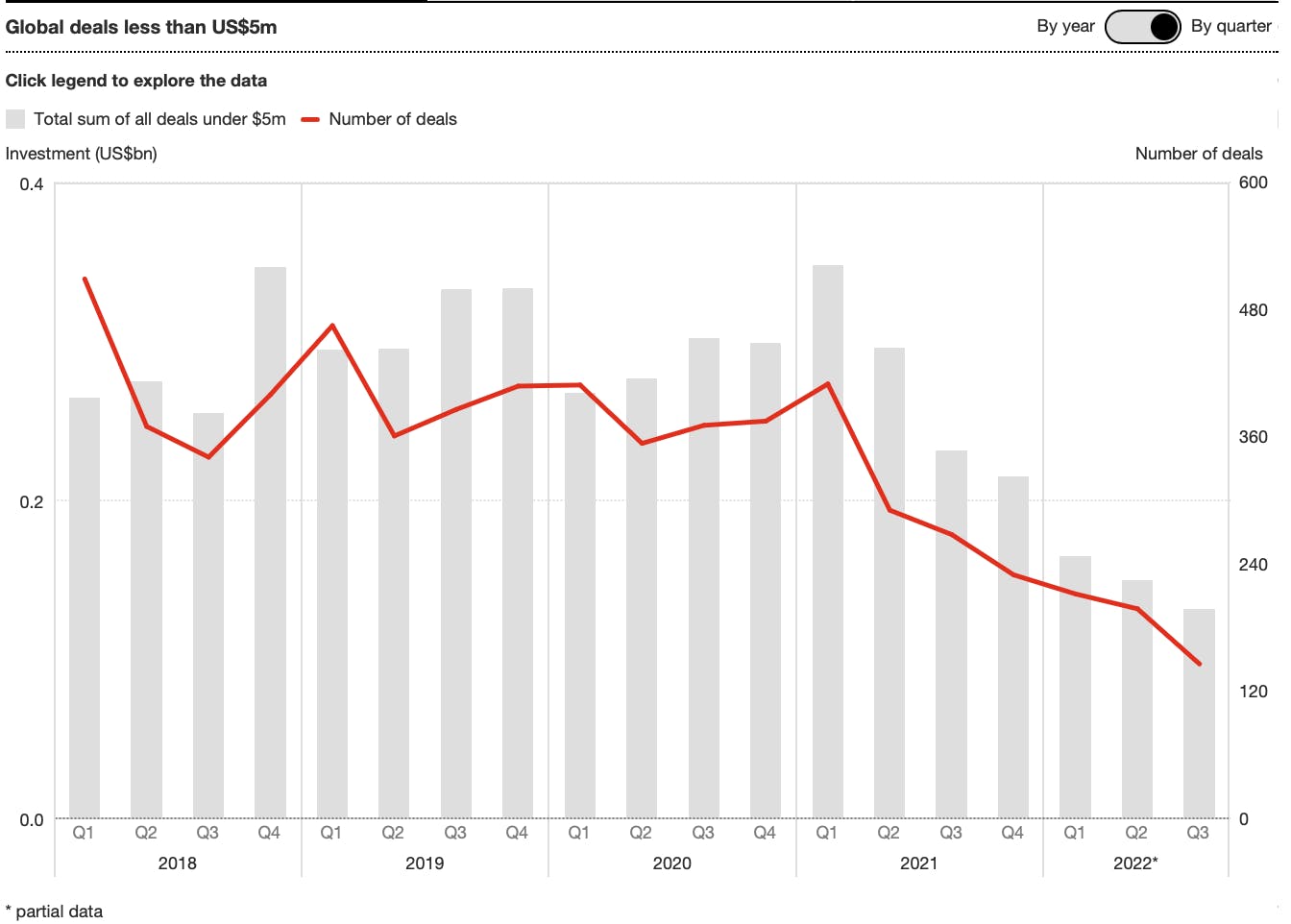

Another troubling climate tech investment trend PwC pointed out was the declining rate of small, but critical early-stage deals, which could not only stifle potentially significant technological discoveries, but also affect the pipeline of mid to late stage climate tech companies. Image: PwC State of Climate Tech report 2022.

Heavy investment in the sector has resulted in strong growth in climate tech jobs, which many tech professionals affected by the mass layoffs in North America and Europe have capitalised on to rebuild their careers. In an interview with Eco-Business, Nishant Mani, chief business officer of climate job and educational platform Terra.do, said they have seen a great increase in the number of new users since the tech layoffs began.

“Since the redundancies started, we’ve seen people with technology backgrounds [like those] with functional skills in software engineering ramp up by over 100 per cent on a daily basis in terms of coming onto the platform, attending job fairs and filling out their profiles,” Mani recounted.

He acknowledged that many tech professionals are often sceptical about building a new career in climate tech, but wanted to highlight that experience in the industry is not usually a must.

“There are exceptions, but the one thing we’ve heard very consistently from all the conversations we’ve had with employers is that they want to bring in people who know their function and skillset incredibly well and have a passion for climate. So, I completely understand the hesitation from those in tech, but what matters is them knowing their function, being interested in the industry and building connections.”

Anshuman Bapna, founder of Terra.do, also pointed out that these skillsets did not necessarily have to be in “hard” disciplines like industrial process automation or software and product development, as 40 per cent of the jobs listed on the site were in traditional business roles like sales, marketing, legal and public relations.

Nevertheless, given that most climate tech companies are still in an early stage of development, Mani stated that joining one from a big tech company like Meta and Twitter would require a substantial “trade-off” between stability and the satisfaction of working in a sector which has a positive impact on the climate on the other.

Furthermore, Asian tech professionals may find it harder to capitalise on the climate tech wave as many websites specialising in climate tech jobs mostly cater to North American and European audiences. When Eco-Business contacted Climate Draft, another climate job platform, it said its network was primarily focused on the United States.

Mani admitted that Terra.do had the “most familiarity” with the Western regions, and that individuals would most likely have to depend on the climate job market in their resident country, as remote jobs are still not the industry norm.

“It varies from sector to sector. I’ve definitely seen some companies offer remote jobs that are open worldwide, but I would not call them the majority. I think the real movement in climate tech jobs is going to come at the local level,” he explained.

Despite these challenges, Mani is convinced that climate tech is the right career choice for tech professionals in the long term, even if they have not been affected by the layoffs.

“We think climate is going to have a transformational impact on sectors that add up to more than 50 per cent of the world’s GDP. Though these industries are still in the early stages of developing climate expertise, they are going to transform and expand quickly. Coming into them now is going to give people a ground floor seat in where we believe the next massive wave of innovation is going to happen.”