Banks in the Philippines continue to finance coal-fired plants despite the looming risk that the plants will not be able to pay back loans for their construction.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Even though President Rodrigo Duterte signed the Paris Climate Accord last year, there has been a coal boom in the country, with 10,423 megawatts (MW) of largely imported coal in the pipeline, amounting to about US$21 billion.

This will add to a total of 7,419 MW of existing coal capacity, according to a study by United States-based think tank Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

A separate study by Carbon Brief finds that the island nation has 12,141 megawatts (MW) of coal power in the pipeline, ranking it as 10th in the world for planned coal-fired capacity.

IEEFA energy analyst Sara Jane Ahmed said that a surplus of coal-fired power has led to more plants turning into “stranded assets”. This means that the project will not have enough cash flow to cover the debt, leading to bankruptcy for the investor.

“Financial models in the Philippines do not take into account that the coal plant is not used as much as expected. If it is used less than 85 per cent of capacity, it affects the project’s ability to pay back the loan. This loan comes from the local banks,” says Ahmed.

The Philippines’ big coal lenders

Rizal Commercial Banking Corporation (RCBC), which ranks 10th among the biggest commercial banks in the country, is one of the active lenders in the power sector listed in a Philippine Movement for Climate Justice (PMCJ) report published in April.

The Yuchengco-owned development bank came under fire last October after PMCJ filed a climate action suit against the bank’s financier, International Finance Corporation (IFC), for allegedly expanding its coal investments in the Philippines. IFC is the private sector arm of the World Bank.

“

I would not agree with the statement that coal plants will become stranded assets in the long term since we all know the coal is the cheapest fuel to produce electricity.

Melita Obillo, director, Energy Resource Development Bureau

According to PMCJ national coordinator Ian Rivera, RCBC is funding 19 coal plants.

Source: PMCJ

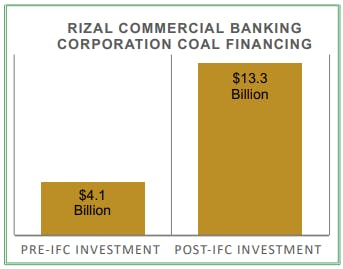

The PMCJ study also found that RCBC received its first loan from the IFC in March 2011, and since then has more than tripled its financial exposure to coal projects and companies.

The report says before IFC’s loan to RCBC, the bank participated in US$4.1 billion worth of publicly disclosed financing for companies involved in the coal sector. After the IFC’s investment, the report states, RCBC began pouring money into coal, participating in approximately US$13.3 billion worth of transactions in the sector, including US$6.4 billion in direct project financing.

The Philippines’ largest commercial bank BDO Unibank, announced two years ago that although it provided over US$600 million in renewable projects, it admitted that investments in coal-fired plants made up around half of its energy investments.

Ayala-owned Bank of the Philippine Islands (BPI) has earned a good reputation in the renewable energy sector, but it was met with protests in October last year when it was found to be subsidising a coal-fired power plant in Atimonan, Quezon province. Earlier, BPI was one of the banks that put together US$525 million to finance a 330 MW power plant by locally-based American power firm AES Corp in Zambales.

Other major local banks that have invested in coal plants include the Philippines’ sixth biggest bank Security Bank as well as Asia United Bank Corp, the 14th largest commercial bank in terms of total assets.

Stranding is already here

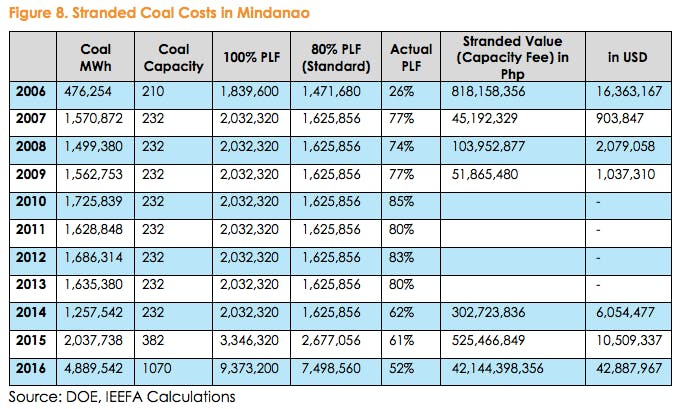

Ahmed noted that stranded coal assets is already an issue in the region of Mindanao due to an oversupply of approximately 700 MW of coal.

The chart below shows that in 2014, the average capacity of energy that the plant was using—known as the plant load factor (PLF)—was 2,032,320 MW. Of this capacity, only 62 per cent was used. This resulted in stranded assets valued at P302,723,836 (US$5 million). From 2014 to 2016, stranded coal assets amounted to P3 billion (US$60 million).

The impact of stranded coal assets does not just affect the banks—it is passed on to electricity consumers who pay more for electricity. In October last year, a Senate resolution was set to be filed to make sure that banks investing in coal-fired projects were not passing on the burden to consumers.

Is the future renewables?

The Philippine’s Department of Energy (DOE) opposes the idea that coal plants could become stranded assets.

In an email interview with Eco-Business, director of the Energy Resource Development Bureau, Melita Obillo said: “I would not agree with the statement that coal plants will become stranded assets in the long term since we all know the coal is the cheapest fuel to produce electricity.”

“I don’t think any country would ban the use of coal-fired power plants to meet their demand for electricity. However, there are technologies which are already being applied to lessen the impact of coal-fired power plants to the environment,” Obillo said.

Obillo said such technologies include “clean coal” solutions such as electrostatic precipitator filters, which capture toxic emissions and prevent them from escaping into the atmosphere. Environmentalists counter that there is no such thing as clean coal, which when burned is the single biggest contributer to climate change.

Meanwhile, the department says it is taking steps to spurr the growth of renewable energy. Through the DOE’s National Renewable Energy Program, the country aims to generate 15,304 MW of clean energy by 2030, and at least 20,000 MW by 2040.

Renewable energy is getting cheaper too. A report from IEEFA shows that the cost of renewables generation in the Philippines is less than coal. However, the high upfront costs of infrastructure, regulatory hurdles and the dominance of the large incumbent players has hindered the widespread adoption of renewables.

Currently, renewable energy accounts for more than a third (36.1 per cent) of the Philippines’ energy mix, while fossil fuels contribute more than half, according to data from Department of Energy.

Mylene Capongcol, director at the DOE’s Renewable Energy Management Bureau (REMB), said: “Increasing the development and use of renewable resources will help mitigate the rising cost of electricity as well as decrease our dependence on imported fuels.”