Nearly 23,000 delegates descended on the coal-tinged city with a deadline for hashing out the Paris Agreement “rulebook”, which is the operating manual needed for when the global deal enters into force in 2020.

This was mostly agreed, starting a new international climate regime under which all countries will have to report their emissions – and progress in cutting them – every two years from 2024.

But as countries wrestled with the “four-dimensional spaghetti” of competing priorities – as one delegate put it to Carbon Brief – they clashed over how to recognise the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) special report on 1.5C and whether to clearly signal the need for greater ambition to stay below this temperature limit.

The final outcome included hints at the need for more ambitious climate pledges before 2020, leaving many NGOs disappointed at the lack of more forceful language. Meanwhile, new research released at the COP showed global emissions were going up, not down.

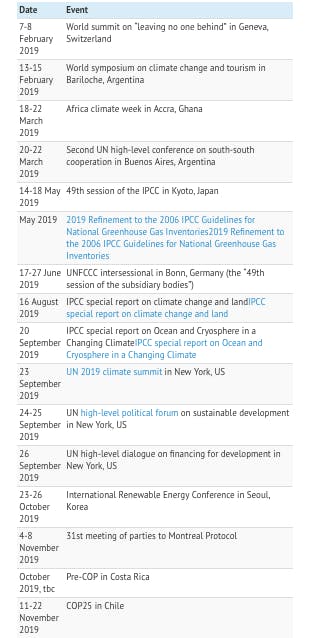

With tension mounting across the fortnight of the talks, UN secretary-general António Guterres had to visit the COP several times to force progress. Despite settling on large parts of the Paris rulebook, countries failed to agree the rules for voluntary market mechanisms, pushing part of the process onto next year’s COP25 in Chile.

Here, Carbon Brief provides in-depth analysis of all the key outcomes in Katowice – both inside and outside the COP…

Polish COP

Poland’s role as host of the UNFCC’s annual talks for the third time in 11 years proved significant.

Its choice to hold the COP in Katowice, in the heart of the coal-dominated region of Silesia, was poignant, particularly as several coal-sector companies were chosen as partners for the talks.

Poland also announced the opening of a new coal mine in the region shortly before the conference began. Around 80% of the country’s electricity currently comes from coal.

Delegates arriving at the talks were met by the taste of coal in the air and high levels of smog, as well as an accolade from the Polish Coal Miners Band. It was very quicklynoted that the Katowice pavilion inside the COP venue featured walls, floors, soap and even earrings all made from coal. “There is no plan today to fully give up on coal,” Poland’s president, Andrzej Duda, told the opening plenary.

However, Poland’s presidency also sought to highlight the issue of a “just transition” for workers away from fossil-fuel jobs. Bert De Wel, policy officer at the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), told DeSmog UK:

“[N]ever, ever, before had climate negotiators debated so much about the impacts of the energy transition on workers and their communities.”

One element of this was the Polish presidency’s launch of the “Silesia declaration”, signed by some 50 countries, during the first week of the COP. It was notable that this total was only around a quarter of the nearly 200 countries present, with the document adopted by acclamation rather than consensus. It was only “noted” in the final COP text.

The declaration emphasised the need for emission-reducing policies to ensure “a just transition of the workforce” that creates “decent work and quality jobs”.

The Polish presidency also launched a declaration on “forests for climate”, highlighting the important role of forests in reaching Paris Agreement goals. However, some NGOs expressed concern that the declaration showed signs that Poland hopes to use carbon offsets from forests to delay efforts to reduce emissions. Others noted the declaration didn’t include any concrete near-term targets.

A further declaration, released jointly by the Polish presidency and the UK, targeted low-emission transport. Joined by 38 countries and 1,200 companies, it urged cooperation to “renew efforts” to help achieve “an e-mobility revolution”.

A further controversy came when Poland reportedly denied entry at its border to at least a dozen COP24 participants. Poland was also criticised by Human Rights Watchahead of the talks for introducing a new law this year which would “hamper the rights of environmental activists to protest” at the climate talks.

‘Welcoming’ the IPCC 1.5 report

The special report on the impacts of 1.5C global warming, published by the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in October, became a major source of tension at the talks.

At the end of the first week, four countries – the US, Saudi Arabia, Russia and Kuwait – delayed the conclusion of a technical plenary by refusing to “welcome” the report. Instead, they only wanted to “note” it, which led furious climate-vulnerable countries to trigger a clause which means the resolution has been postponed until the next SBSTA session in 2019.

The 1.5C report had been originally formally requested by countries at the 2015 climate talks in Paris, and despite the majority of countries speaking in favour of the report.

In an exclusive interview with Carbon Brief, Saudi Arabia’s senior negotiator Ayman Shasly sought to explain why his country was hesitant to welcome a report that had, as he claimed, “scientific gaps [and] knowledge gaps”.

The wording was somewhat fudged in the final COP decision text. It did not “welcome” the report, but did welcome its “timely completion” and “invited” countries to make use of the report in subsequent discussions at the UNFCCC.

Another report also helped to set a sense of urgency at the talks. During the first week, the latest annual estimates of global emissions from the Global Carbon Project (GCP)found that output from fossil fuels and industry will likely grow by around 2.7 per cent in 2018, the fastest increase in seven years.

Paris rulebook agreed

At the heart of talks in Poland was the Paris “rulebook”, which was mandated in 2015 to be finalised by the end of COP24. This is the detailed “operating manual” needed for the Paris Agreement to enter force in 2020.

The rulebook covers a multitude of questions, such as how countries should report their greenhouse gas emissions or contributions to climate finance, as well as what rules should apply to voluntary market mechanisms, such as carbon trading.

Two common threads ran through each area of these areas. First, whether to agree a single set of rules for all countries – with flexibility for those that need it – or to maintain the current divide between rules for rich and poor. This is referred to as “differentiation”, or sometimes “bifurcation”.

The second thread was the provision of climate finance to help developing nations adapt to the impacts of global warming, mitigate their emissions and participate fully in the Paris process.

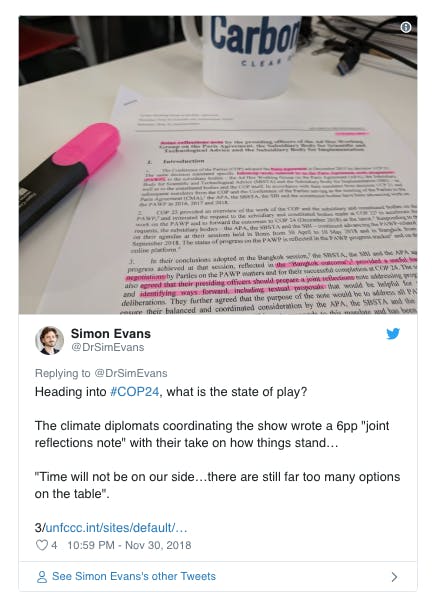

Ahead of the COP, the “co-chairs” and “co-facilitators” of the technical talks had tried to improve on the 307 pages of draft rulebook text that emerged from talks in Bangkok, Thailand, in September. They had whittled this down by mid-October to a series of nine “addendums” covering 236 pages.

This left negotiators with a far larger and more technical task than they faced before the Paris COP21 in 2015. Indeed, heading into the talks at Katowice, the climate diplomats coordinating the process warned: “Time will not be on our side…there are still far too many options on the table.”

Despite this time pressure, negotiators repeatedly missed deadlines for new versions of their texts during the first week at COP24. This meant technical talks spilled into week two, continuing alongside high-level ministerial sessions after having officially closed late on the middle Saturday.

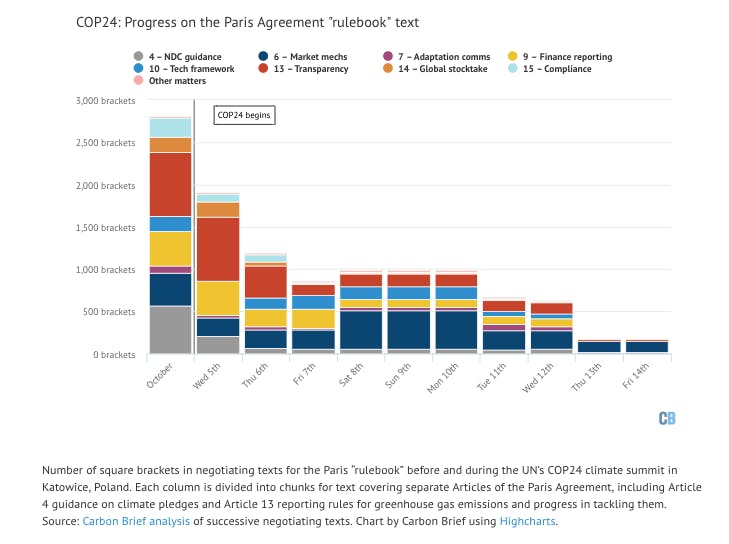

Carbon Brief tracked the negotiating texts throughout the session in an open-access spreadsheet. This records the number of pages of text in each iteration, as well as the number of square brackets – indicating areas of disagreement – and the number of different “options” still on the table.

Starting with nearly 3,000 brackets before the talks began, negotiators faced an uphill struggle to move towards “clean” text – with zero brackets or options – on which all could agree.

Part way into week two the talks reached a crunch phase, with COP president Michał Kurtyka telling delegates: “The current approach to negotiations is exhausted. Many texts are stuck. From now on we will move under the authority of the Polish presidency.”

In practice, this change of gears meant that the presidency took ownership of the texts – a tricky balancing act between making progress and angering those countries or blocs whose language was lost. The resulting shorter texts can be seen from 11 December in the chart, below.

The chart, above, also shows some of the rulebook sections that proved most difficult to resolve. For example, these included provisions for voluntary market mechanisms under Article 6, standards for climate finance reporting under Article 9, and the rules on transparency under Article 13, which cover reporting of greenhouse gas emissions and progress in tackling them.

The Polish presidency produced a second iteration of texts during Thursday of week two. These drafts dramatically reduced the number of outstanding square brackets from more than 600 down to around 180, but left many groups unhappy.

Finally, a much-delayed late-night plenary on Saturday, 15 December, signed off the rulebook with zero brackets and options remaining.

Overall, the deal tends towards single sets of rules for all countries, with wide latitude for those that lack the capacity to meet them. On finance, the rules are relatively permissive, giving flexibility to rich nations in what and how they report their contributions. (See below for analysis of the key sections of the text.)

One casualty was the complex and technical Article 6 rules for voluntary carbon markets. This had been effectively held hostage by Brazil, which tried to water down rules to stop “double counting” of emissions cuts by the country where they were generated, as well as the country buying the offsets.

Unable to reach agreement, the talks instead passed the matter to next year’s COP25 in Chile. The COP24 decision on Article 6 reads: “Draft decision texts on these matters in the proposal by the president were considered, but…parties could not reach consensus thereon.”

Climate pledge guidance – Article 4

Countries’ climate pledges (“nationally determined contributions”, NDCs) are mandated by Article 4 of the Paris Agreement. The rules around what should be in them are supposed to make it easier to compare pledges and to add them up as a global aggregate.

To this end, the final decision says that all countries “shall” use the latest emissions accounting guidance from the IPCC, last updated in 2006, but now in the process of being refreshed next year.

One significant difference between the 2006 guidance and earlier versions is an update to a higher “global warming potential” for methane, says Dr Robbie Andrew, senior researcher at Norway’s CICERO climate science institute. His colleague Dr Glen Peterstells Carbon Brief that a shift to all countries using the same accounting rules would be “brilliant” for researchers.

However, Dr Joeri Rogelj, a lecturer in climate change at Imperial College London’s Grantham Institute, tells Carbon Brief: “Some aspects do raise concerns about the environmental integrity of NDCs [climate pledges].” He points to leeway over the choice of accounting rules:

“Under the Paris Agreement, emissions and proposed emissions reductions will be regularly compared, added up, and assessed in light of their adequacy for limiting warming well below 2C and 1.5C. This requires common rules for emissions reporting. But instead of requiring countries to adhere to scientifically robust methods, the final Katowice text now allows countries to use ‘nationally appropriate methodologies’, which, in all likelihood, will only be used to do some creative reporting and portray emissions of specific countries in a better light than they are. This is particularly an issue in the land-use sector.”

Additionally, countries agreed that their pledges will be recorded in a public registry, based on the existing interim portal. This will continue to include a search function, despite attempts to have it removed.

There was also agreement that pledges should cover a “common timeframe” from 2031, with the number of years to be agreed later. Some current pledges cover five years while others cover 10.

Market mechanisms – Article 6

The most technical area of text was on rules for voluntary market mechanisms under Article 6. This includes Article 6.2 where, for example, countries can trade overachievement of their climate pledges, as well as Article 6.4, under which individual projects can generate carbon credits for sale.

Discussions struggled to move forward throughout the two weeks in Poland, with the number of bracketed sections remaining stubbornly high (see chart, above). As the days passed, more and more details of the Article 6 rules were added to the to-do list for 2019.

Towards the end of week one, co-facilitator of the talks Kelley Kizzier told a side event: “I think we are starting to see some landing zones [for agreement], but it’s still cooking.” In the end, it was not to be and the whole section was deferred to COP25.

The most contentious point was on basic accounting rules to prevent “double counting” of emissions reductions by the buyer and seller of offsets. The draft text set out how each party should make a “corresponding adjustment” to their emissions inventories to reflect the trade.

“It was Brazil versus the rest of the world and they wouldn’t back down,” one business source following the talks tells Carbon Brief. “Brazil wanted to have its cake and eat it”, the source adds.

One additional subtlety to the arguments around double counting relates to emissions cuts taking place in sectors not covered by a country’s climate pledge (“outside” the NDC, as opposed to “inside” it). This matter appears to have been unresolved as of the end of COP24.

Article 6.4 is intended to replace the Kyoto Protocol’s “Clean Development Mechanism” (CDM) for carbon offsets. Discussions in Poland included how or whether to carry forward the offsets, schemes and methodologies drawn up under the CDM – and whether to place limits on their use for meeting pledges under the Paris Agreement. Talks will continue next year.

This failure at COP24 will create a headache for CORSIA, the trading scheme being set up for aviation emissions. The UN’s aviation body ICAO is due to start agree CORSIA rules next spring and is expected to have to remove any reference to Article 6 markets, at least initially.

One final issue under discussion within Article 6 was “overall mitigation in global emissions” (OMGE). This language was introduced by the Paris Agreement to explain the idea that carbon trading should generate a net benefit for the climate, rather than being a zero-sum game.

Early drafts included options that would have automatically cancelled up to 30% of all offsets generated. Analysts, climate vulnerable countries and many NGOs said automatic cancellation was necessary to ensure OMGE. However, later versions of the draft text made cancellation voluntary.

The failure to agree rules for Article 6 was “disappointing”, says Gilles Dufrasne, policy officer at Carbon Market Watch, an NGO. However, he tells Carbon Brief this was a better outcome than “adopting the unacceptable position which Brazil was pushing”.

According to Nat Keohane, head of climate at the Environmental Defence Fund in the US, countries will be able to move ahead with voluntary carbon trading, despite the failure to agree Article 6 rules.

The Paris Agreement says such trading should be “consistent with guidance”, but does not disallow it if no guidance exists, Keohane argues. He adds that this was worded deliberately to “Brazil-proof” voluntary market mechanisms against attempts to sabotage agreement on the rules.

It is not yet known how the incoming Jair Bolsonaro-led government in Brazil will approach this issue.

Climate finance reporting – Article 9

Ahead of COP24, the rules governing climate finance reporting under Article 9 of the Paris Agreement were expected to be contentious. Yet negotiators made surprisingly rapid progress.

The rules cover Article 9.5 (reporting on the projected availability of climate finance in future), as well as Article 9.7 (reporting on money that has already changed hands). The final rules say developed countries “shall” and developing “should” report on any climate finance they provide.