Southeast Asia’s response to the Covid‑19 outbreak has curtailed electricity use and industrial production, pushing down coal consumption even further this year, according to the latest report from a non-governmental organisation which monitors worldwide fossil fuel infrastructure.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Even before Covid-19, new coal plant construction was already slowing in the region, which is home to three of the world’s 10 largest coal pipelines. But the pandemic further accelerated the region’s transition away from the fossil fuel as it caused delays in coal plant construction, revealed a study released on Monday (3 August) by Global Energy Monitor (GEM).

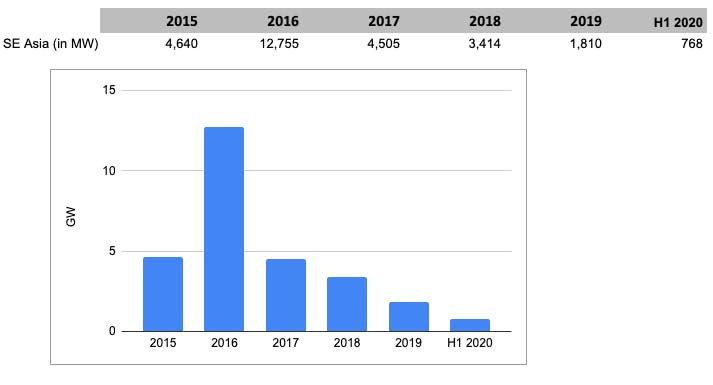

Only one gigawatt (GW) of coal power was newly proposed and 0.8GW started construction in the first half of 2020. This is 70 per cent lower than the average 2.9GW of new proposals and 2.7GW of new construction every six months in the region since 2015, said the study’s lead author Christine Shearer.

“I do think Covid will [continue to] accelerate the transition away from coal in Southeast Asia,” said Shearer, who is also the director of GEM’s coal programme.

“Covid is also lowering projections of future energy demand, at least in the near-term, and with its higher fuel costs over solar and wind, plans for new coal plants may be among the first to be cut.”

The chart shows a 70 per cent decline in new coal construction from the 2015–2019 average. Southeast Asia averaged 2.7GW of new coal construction every six months since the start of 2015 but this dipped to 0.8GW in the first half of 2020 (H1 2020). Image: Global Energy Monitor

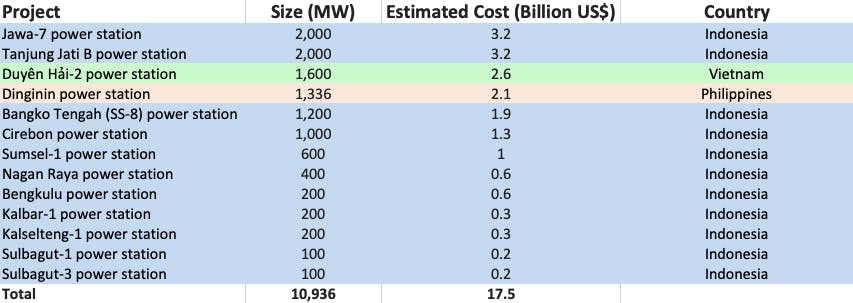

The results from the Global Coal Plant Tracker published by GEM showed Indonesia bearing the brunt of the pandemic’s impact.

Indonesia, whose 8,000-megawatt (MW) of new coal construction makes up the bulk of the stalled projects in the region, declared delays in its projects due to obstruction of supply and raw material for the plant components. The government also imposed a nationwide lockdown aimed at containing the coronavirus outbreak in the country, which prevented entry of workers from China.

But prior to the outbreak, the world’s fifth biggest producer of coal already signaled a move away from the fossil fuel due to a dip in its prices amid dwindling demand.

“

Covid is lowering projections of future energy demand, at least in the near-term, and with its higher fuel costs over solar and wind, plans for new coal plants may be among the first to be cut.

Christine Shearer, coal programme director, Global Energy Monitoring

The Philippines’s proposed 1,336MW Dinginin power station in Bataan was stalled because Chinese engineers who were part of the plant’s testing and commissioning processes were subject to a Covid-19-related travel ban. Local workers were hired to speed up construction but the project still could not be completed as planned. It was targeted to start operating by June, but has been pushed back to third quarter of this year.

In Vietnam, foreign workers for the Duyên Hải-2 power station were also prohibited from entering the country. The facility is expected to go online in June 2021, but plant owners admit that the outbreak is “challenging our construction schedule”. The pandemic aside, Vietnam has already been mulling canceling almost half of its planned coal power capacity as alternative sources of energy take up growing shares in its power mix.

A list of coal-fired power plants in construction delayed by Covid-19 workforce or supply chain issues in Southeast Asia. New coal in the pipeline is predominantly in Indonesia. Image: Global Energy Monitor

Elsewhere in Asia, India had no new construction in the first half of 2020 and shrank its coal fleet by 0.3GW. Restrictions to combat the spread of the coronavirus have caused a lack of spare parts from Chinese suppliers for coal plants and coal mines, as about 30 per cent of the 62,000MW of coal projects under construction in the country rely on Chinese suppliers.

India, the world’s second largest coal supplier, has been reducing its share of global coal power development, from 17 per cent of the world’s pipeline in mid-2018 to 12 per cent in mid-2020.

In Bangladesh, the coronavirus pandemic is also affecting the construction of the controversial Rampal coal plant as it was reported to be running far behind schedule at only 50 per cent completion and significantly over budget. The plant was supposed to have been finished by June. Protesters have opposed the construction of the project on a site adjacent to the UNESCO protected Sunderbans mangrove forest.

Pakistan’s Thar Block II power station and coal mine were delayed as well, with 120 workers from China banned from entry.

While the world shrinks its coal, China surges ahead

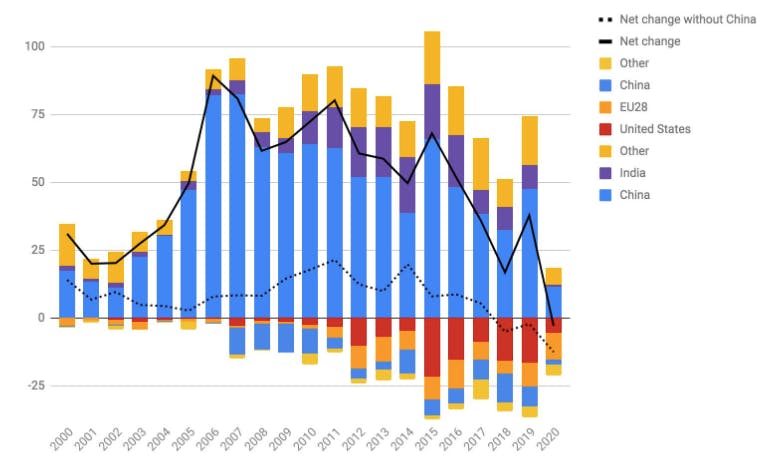

When the worst effects of Covid-19 in China began to subside, new coal plant permits in the country soared, the GEM report said. From 1 to 18 March 2020, more coal-fired capacity was allowed for construction in China (7,960MW) than in all of 2019 (6,310MW).

The increase may signal a move by government officials to use new coal plants as a means to boost the country’s domestic economy after the slowdown from the pandemic, GEM’s Shearer said.

But China is estimated to already have 400GW of excess coal power capacity compared with the capacity needed to ensure adequate supply. This, Shearer noted, is worrisome.

“The excess capacity means operating hours are spread out among a large number of plants, reducing their average utilisation rates, thus reducing revenues. Adding more coal plants will only contribute to this problem,” she said.

Low utilisation rates refers to low, negligible or negative profit margins, which have caused a number of coal power plant operators to go bankrupt due to lack of demand.

Annual net coal power additions and retirements (coloured columns) and the net change with China (black line) and without China (dotted black line). Image: Global Energy Monitor

Despite large capacity additions in China, the world’s fleet of coal-fired power stations has gotten smaller for the first time in history, the GEM report noted.

The 2.9GW decline in the first half of 2020 takes the global total down to 2,047GW. The fall was due to a combination of slower commissioning due to the Covid-19 pandemic and large-scale retirements in Europe of 8.3GW from strengthened pollution regulations.

But figures in the report show that 189.8GW of coal power capacity is still under construction globally and another 331.9GW is being planned.

This runs counter to calls from United Nations secretary general António Guterres for a global moratorium on new coal plants after 2020, said Shearer.

Global coal power generation needs to fall by 50 per cent to 75 per cent below current levels by 2030 to keep warming well below 2 degrees Celsius, according to the report.